|

There are large files and images on this page please wait while loading

|

|

|

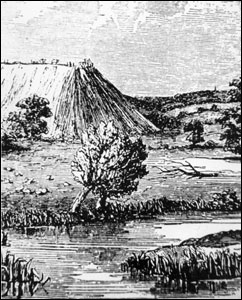

Wolverton viaduct, one of the engineering miracles of the railway line.

It has had its problems, especially when, as above, the embankment began to slip. |

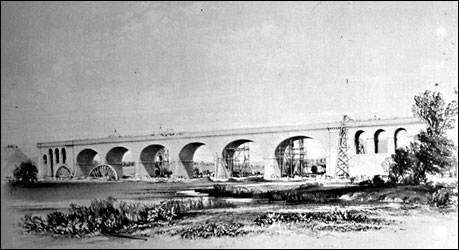

The Viaduct c.1838

|

| THE VIADUCT Wolverton Express Sept 3, 1971 When in 1838 the first travellers steamed along the newly opened London to Birmingham railway, they would have been interested to see the new settlement of Wolverton, created out of an almost deserted Bucks valley to be the central depot of the county’s new engineering venture, the “milestone of railway engineering” as it was described at the time. We can imagine the surprise and the pride of these travellers from a series of lithographs drawn by John C. Bourne and published in 1839, showing the newly opened railway from its Euston Square terminus to Birmingham. Bourne’s draughtsmanship is of a high quality and is faithfully reproduced in a book reprinted and published by David and Charles (Publishers) Ltd., of Newton Abbot, Devon. Underestimated Engineer in chief of the line was Robert Stephenson, whose famous “Rocket” had achieved the somewhat staggering speed of 29mph. But Stephenson underestimated the cost of the new enterprise which totalled over £6 million, at £50,000 per mile. His estimate was £21,176 a mile. The industrial consequences, however, were thought to be well worth this outlay. Two of the main industrial cities in the country, indeed in the world, were linked by the steam empire. Royal assent to the London to and Birmingham Railway Act was given in May 1833, whereupon work started on several important features along the line: the Iron Bridge over Regent’s Canal, and the Wolverton Embankment. Building of the line met with several difficulties. The financial problems forced Parliament to pass several Acts to meet the increasing cost, as well as an Act to move the London Terminus from its original place at Camden Town to the more familiar surroundings of Euston Square, owned by the Duke of Grafton. John Britton’s notes describe the line’s entry into North Bucks: “After traversing two embankments in Soulbury and two others in Stoke Hammond, the line reaches the Holyhead Road: and here, at a place called Denbigh Hall (from the name of a public house) was a memorable station to which London trains conveyed passengers and luggage, and thence returned to the metropolis with the other, the intermediate distance from the Station to Rugby being travelled by stage coaches from April to September 1838. Roman road “The crossing of the turnpike road is by a bridge of great extent. It is stated that part of it is based on the foundations of a Roman bridge: the celebrated Watling Street of the Romans having occupied the site and line of the present Great North Road. “The whole length of the bridge is 200 feet and the height from the road to soffit of the arch is twenty feet. “The intersection takes place at an angle of twenty five degrees. The iron work amounts to 160 tons. “In the same parish (Bletchley) is Whaddon Hall, which was the residence of Browne Willis, an antiquary and author of repute at the beginning of the last century. The village church and other objects in the neighbourhood are entitled to the particular attention of the topographer. “The small decayed market-town of Fenny Stratford is partly in this parish and partly of that of Simpson. “Soon after passing Denbigh Hall Bridge, the Denbigh Cutting commences which extends about three-quarters of a mile, and varies in depth from thirty two to forty feet. On the left is the village of Loughton, the massive tower of whose church rises amidst a clump of fine trees. Other embankments and excavations ensue, the village of Bradwell being on the right. Central depot “The combination of public roads and the Grand Junction Canal with the railway, near the village of Wolverton, fifty-two miles and a half from London and sixty from Birmingham, induced the engineer to fix on the point for a Central Depot and Station and to make it a magazine and manufactory of great consequence to the whole line. “Here have been erected a locomotive engine-house, 314 feet square, provided with tender sheds, and iron foundry, smithy, boiler-yard, hoping furnaces, iron warehouse, a steam engine for working the machinery, turning shops and lathes; cattle-sheds, a depot for goods, booking offices with waiting and refreshment rooms, and a new colony of cottages and dwellings for the workmen and their families. Hence a small town, or village is established in a district previously unoccupied. “At this station the railway crosses the Grand Junction Canal, for the forth time, by an iron bridge with horizontal main ribs and then enters upon the great Wolverton Embankment which extends across the valley of the Ouse to an extent of one mile and a half, being the longest on the line: it averages 48 feet in height, and is composed chiefly of clay, gravel, sand and has limestone. “In its course is a viaduct consisting of six principal arches of an elliptical form, having a span of 60 feet, each and rising 46 feet from the ground to the crown. “In the abutment at each end of the viaduct are two bold pilasters, and four sub-ordinate arches; a stone cornice runs through the whole, which is 660 feet in length, and 57 feet high to the top of the parapet. “Beneath one of the main arches is an artificial channel, formed by the Company for the united waters of the River Ouse and a smaller stream called the Tow, which formerly flowed separately through the valley. “The appearance of the viaduct when nearly completed with a portion of the centering used in forming the main arches and the scaffolding for raising the stone and other materials is shown in drawing above. Embankment slip The drawing (at the top left) shows one of those slips, or sinkings which occasionally occurs during the formation of the large embankments. From the wetness of a part of the soil used in the present instance, the super-incumbent weight caused it to bulge out at the bottom, until it had spread out at the bottom, until it had spread in a lateral direction to nearly 170 feet; and it was found necessary to build a temporary wooden bridge across it, to carry on the embankment, until it had become sufficiently firm to bear more earth upon it. “A portion of the earth used in one part of the work was alum shale, containing sulphate of iron which becoming decomposed, spontaneous combustion ensued and burnt the sleepers laid upon the surface. “ An extensive and lofty embankment, which like that at Wolverton, was of very difficult formation succeeds, and in its course divides the village of Ashton into two parts. Victoria Bridge “To the eastward, are Wakefield Lodge and Stoke Park, the seats of the Duke of Grafton and of Wentworth Vernon Esq., the view being bounded by Whittlewood Forest, of which his Grace is Warden. “The short cutting beyond Ashton is crossed by a bridge of blue stone which, from having been finished on the day of Her Majesty’s accession, is named Victoria Bridge. “Half a mile beyond Ashton and 60 miles from London is the village of Roade, where since the opening of the whole line of railway, a Principal Station has been established on account of the facility which affords for commuting by coach with Northampton only four miles distant, and thence to Nottingham and to Leicester, and to other places.” And so on to Birmingham where, Britton claims: “Every grade of the human race, from infancy to old age, is called into active exertion to produce the numerous and diversified articles of usefulness and luxury, which are made in this mechanical emporium.” An extract from "The Railway Navvies " by Terry Coleman The principal works of the navvies were banking, cutting, and tunnelling. In embanking the aim was always to extract the necessary soil from the nearest possible place, and the engineers would have allowed for this when they first surveyed the way. One method was to take the earth from a side cutting, so that the finished work would consist of a raised embankment with a ditch running on one or both sides. This was done where there was no other feasible way of getting the soil wanted, but the more frequent method was to cart the soil to an embankment from a cutting a little farther back. This was done by tipping. A light tram road was made from the cutting to the edge of the embankment, and at the extreme verge a stout piece of timber was fastened to prevent the wagons toppling over the edge when they discharged their contents. A train of loaded trucks was then brought up to within fifty yards of the edge, and the first truck was detached from the train and a horse hitched to it. The horse that drew the wagon walked not directly in front of it between the tram lines, but to the side of the track, as if it were a canal horse on a towpath drawing a barge behind and to its side. The horse was made to walk, then trot, then gallop. When the truck got near the embankment edge the man running with the horse detached its halter, gave it a signal it had been taught to obey, and horse and man leaped aside. But the truck continued until it struck the baulk of wood laid across the end of the track, when it tipped forward, ejecting its contents over the edge of the bank. The horse was immediately brought up again and hooked on, and the truck was righted and drawn away to join an empty train waiting to be taken back to the cutting. In large works two lines of rails and two teams of horses and wagons would work together. If the soil did not fall just where it was wanted the spades of the navvies did the rest. As a boy, John Masefield, who was to become the Poet Laureate, saw a new branch line made from Gloucester to Ledbury, and watched the navvies tipping. Much later he wrote: The earthwork was manned by gangs of Public Works men who soon could be seen high up on the embankment top with trucks and horses working all day long at a game delightful to us to watch. They were employed in building the embankment by trolley loads of earth. The loaded trolleys were drawn along the top of the work by clever horses which knew exactly, or were made exactly to stop and turn aside at the proper instant. The horse went aside, but the truck went on and at the critical moment at the right spot was checked and tipped with its tons of material. We could never see the device at work, but they delighted by their precision and skill. . . . Now and then to this day, I wonder where the Public Works men found all the earth that they tipped to make that strong embankment, shall we say half a mile long, thirty feet high, at least twenty feet broad at the top and three times that breadth at the base. We could never see them loading the trucks, and never could find any big gap in any known landscape. No one was able to inform us. The earth was found I know not where, and used with great skill, leaving no great pit to show whence it had come.

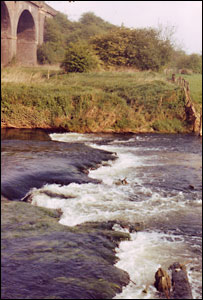

Extract from "Haversham Estate And the Parish I Grew Up In" by David C. Brightman April 2000 The Viaducts were built in 1838 at a cost of £30,000, and in 1878-82 the width was doubled, from 2 to 4 lines on the eastern side. I remember going with dad on one dark night in the early 1950s to patrol the Viaduct, he was armed with a pickaxe handle and a whistle. This was to deter any wrongdoers from sabotaging the Royal Train when it went over the Viaducts on its way to Scotland. I was armed with a .22 Webley air pistol! He reckoned I knew my way around up there better than he did, for this was another hangout of the more adventurous kids. On the Bradwell side there used to be a platelayer’s hut, we made good use of this at odd time for illicit smoking sessions and plotting scrumping tactics! Next to this hut, and demolished in April 1990, was a pumping station which was redundant when the line was electrified about 1965, this used to suck water from the river, or a river fed well and send it to the still standing water tower and the now filled in reservoir at Castlethorpe behind Mr Mayes’ farm, this supplied the steam train water troughs, this water was scooped up by a kind of chute under the speeding steam engine, this was quite a sight, water sprayed everywhere, more like a lifeboat being launched down a slipway. Outside the door of this pump house was a large steel plate, on its removal there was a steel ladder going down quite a depth to a 3ft high tunnel which appeared to go right under the railway bank, this, as you can imagine, we never really explored, mainly because there lots of rabbit skeletons and also a pair of wellington boots, once we found them that was as far as we dare go! The water levels are now much lower than 45 years ago, the water used to flow through the next arch as well until it silted up, there used to be two or three very tall, willow trees there that leaned over towards the Viaduct, and were cut down about 1952. In the early 1950s there was the Polio scare, and swimming in the river by us kids practically died out overnight. Wolverton Viaduct & Embankment

|