|

Extracts from: "The Story of Haversham" by Rev. Samuel Hilton, M.A. Rector of Haversham

|

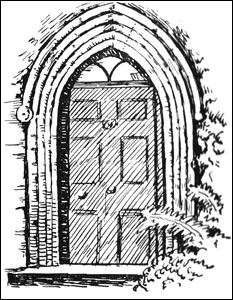

The Romans A brass coin from the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161 to 180) was found at Haversham. Also a steelyard weight in the form of a woman’s head. Many Roman coins were ploughed up in Victorian times in the Freeboard neighbourhood at the north east corner of the parish, where there are traces of an ancient earthwork with steep banks. The Anglo Saxons After the Roman withdrawal around 410 AD the Angles and Saxons began to arrive, and were well established in the Haversham area by 570 AD. There is a local tradition that a desperate battle was fought at Briton’s Piece, between the village and the present Rectory, and that the Christian Romano-Britons held out against the heathen invaders, being either slaughtered or driven eastwards. The 7th century “Tribal Hidage” records that the northern part of Buckinghamshire was occupied by tribes of the Middle Angles, one of which was called the Herefinna. Haversham is considered to be a typical instance of an early Anglo Saxon settlement, being near a road or river, with its manor and church on higher ground at one end of the village. The name of the chief who settled here is assumed to have been Haefer, in Old English meaning “he-goat”, but there is no documentary evidence for such a person. In Old Scandinavian the name Hafr is common, and so Haversham, originally spelled Haefaeresham could mean the home of Haefer. Return of Christianity In the 7th century two missionary efforts began – Birinus, consecrated by the Bishop of Genoa, arrived in Hampshire in 634 and established Christianity in Wessex, presiding at Dorchester. In the north, St Aidan’s in 635 mission came from Northumbria, through Mercia, joining with the previous movement in Wessex. It is not known whether there was a Christian church in Haversham in Anglo Saxon times, but it is deemed not unlikely. There is an ancient yew tree, thought to be over 1000 years old, in the Rectory garden, and the outline of an ancient large building is 55 yards from this spot. The Danes The 9th century brought chaos in the form of invasion by the Danes. In 878 Alfred made treaty with them by dividing the country, and Haversham was left just inside the Danelaw – the adjoining parish of Castlethorpe suggests Danish origin in its name. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c.966 | Aelfgifu (or Elgiva), a kinswoman of King Edgar, to whom she left it in her will.

Appendix A Extracts from the will of AELFGIFU, Translation as given in “Anglo-Saxon Wills” edited by Miss Dorothy Whitelock; reproduced by her kind probation. This is Aelfgifu’s request of her royal lord, she prays him for the love of God and for the sake of his royal dignity, that she may be entitled to make a will. Then and she makes known to you, Sire, by your consent what she wishes to give for to God’s Church for you and for your sold. First she grants to the Old Minister, where she intends her body to be buried, the estate of Risborough just as it stands, except that, with your consent, she wishes that at each village every penalty enslaved man who was subject to her shall be freed . . . . (1) Aethelwold was Bishop of Winchester 963-984. (2) Aelfweard was her brother and was Ealdorman Mancus was a term used in early medieval Europe to denote either a gold coin, a weight of gold of 4.25g or a unit of account of thirty silver pence. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c.1059 | Countess Gueth, widoe of Ralph, Earl of Hereford. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1068 | conferred on William Peverel, baron, by William the Conqueror. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1086 |

Haversham was a settlement in Domesday Book, in the hundred of Bunsty and the county of Buckinghamshire. It had a recorded population of 29 households in 1086, putting it in the largest 40% of settlements recorded in Domesday. Land of William Peverel Households

Land and resources

Valuation

Owners

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1113 | William Peverel, baron, his grandson, was in high favour with the Conqueror, who gave him property in Northampton, Nottingham, Leicester, Derby and nine manors in Buckinghamshire and a castle in the Peak Forest. He was custodian of Nottingham Castle and ancestor of “Peverel of the Peak”, immortalised by Sir Walter Scott. He held Haversham “in demesne”, meaning that he actually lived there.

He founded an abbey at St James in Northampton in 1004 AD. His second foundation was the priory of the Holy Trinity at Lenton in Nottingham between 1109 and 1113. William Peverel later appointed a tenant, “Walterus Flammeth” to take charge of his manor at Haversham. His death is recorded in the register of the Priory of St James in 1113 AD. His son William had died three years previously. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1138 |

William Peverel the Younger, his grandson, was prominent during the reign of King Stephen, and supported him against Matilda, daughter of Henry I. William attended the Great Council at Oxford in King Stephen’s retinue. In 1138 Peverel was one of the chief commanders victorious over the Scots at Northallerton when David of Scotland invaded England. Peverel was captured with King Stephen at Lincoln, in 1141, by Matilda’s forces. Although Matilda’s army took Peverel’s castle at Nottingham, Peverel’s men recaptured it and expelled her followers from the town. But in 1154 King Stephen died and Peverel’s estates were forfeited to Matilda’s son Henry II. Two years previously Henry had promised Peverel’s lands to Ranulf, Earl of Chester, and shortly afterwards, when Ranulf died of poisoning, Peverel was assumed to be responsible. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1154 | Peverel disappeared from public life when Henry II succeeded, and it was said that he took refuge in various monasteries as a monk, never being heard of again. Haversham, with all Peverel lands, were seized by Henry II, but for the next 400 years appeared in various documents as “of the honour of Peverel”. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1174 |

The De Haversham Family The de Haversham family suddenly appear as lords of Haversham twenty years later, around 1174, already named after the village. In that year Robert de Hauerisham failed to appear at his neighbour’s court in a case of melting down coins to test them. He was fined one mark by the Treasury. In the same year Nicol de Hauerisham paid 20 marks to the Treasury when King Henry II gave his daughter to William de Bell in marriage. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1190 |

There is no proof of the relationship between Robert and Nicol, but the de Havershams held the manor for 500 years after this, “of the King in chief by service of one knight’s fee as of the honour of Peverel”. At this time the boundaries of the village were not settled as today, and in 1190 Hugh de Haversham paid 30 marks to investigate whether the wood of Haversham belonged to his estate or to King Richard II’s demesne. In 1199 he paid a similar amount to King John to confirm the same charter. The accounts show that he only paid 20 marks and the rest remained owing (“et debet xm”). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1207 |

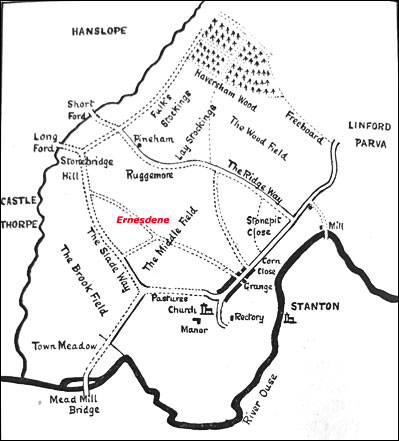

Appendix B. BETWEEN HUGH DE HAVERSHAM AND A translation of “ Pedes Finium,” Hunter, page 242. This is the final agreement made in the King’s Court at Merleb’ge (Marlborough) on the 15th day after the feast of saint Martin, in the 9th year of the reign of King John, in the presence of the lord King himself (and others named) . . . . Between Benedict De Haveresham tenant, concerning 42 acres of land with appurtenances in Haveresham. One thing was agreed between them in the her aforesaid court namely, that the aforesaid Benedict recognise the whole forementioned land with appurtenances to be lawfully Hugh’s own. Ernesdene: the name is derived from the Old English word “erne,” an eagle, and “dene,” a wooded valley. It is probably in the neighbourhood of the fields called Arden Well. Lauedistoking: that is, or clearing surrounded by stakes. It is the present Lay Stockings, alongside the wood to the north of the Ridgeway. Ruggemore: from the Old English word “rugge,” a ridge, and “more,” are Heath or waste land. It is the high ground which the Ridgeway crosses, and is probably somewhere about the field now called Rowditch. The Ridgeway and Lay Stockings rise to a height of 323 feet above sea level, or about 120 feet above the village. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1221 | Sir Nicholas de Haversham succeeded his father, Hugh, and did homage for the Knight's fee in Haversham. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1233 | These disputes continued for years, but in 1233 free right of warren in the manor and fields of Haversham was given to Hugh’s son Nicholas and his heirs. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1242 |

By 1242 the title of the family to the possession of the estate was considered to be of old standing, as shown in the Buckinghamshire Book of Fees: “Comitatus Buk. Haversham. De veteri. Nicholaus de Haveresham cum suis tenentibus tenet unum feodum de honore Peverel” |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1251 |

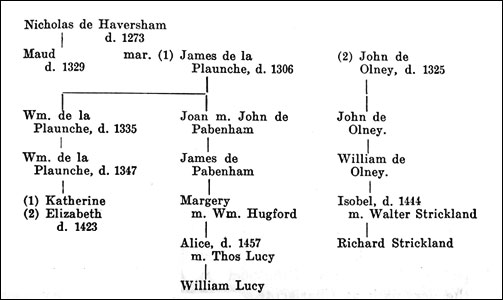

In 1251 Nicholas de Haversham died, leaving a widow, Emma. His son. Also Nicholas, came to be styled “Lord Nicholas of Haversham, and was Constable of Northampton Castle in 1264. He gained further lands in Leicestershire and Wiltshire. He died in 1273, and with him the succession of the de Haversham name to the manor also ceased. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1273 | Maud (or Matilda) his daughter, aged 6 months; custody of the Manor granted to Queen Eleanor. The Queen had custody of the Manor, and the King retained the advowson of the patronage of the Rectory. The value of the Haversham lands was estimated at £58 8s 3½d. Maud married- The Inquisition of 1273.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1278 |

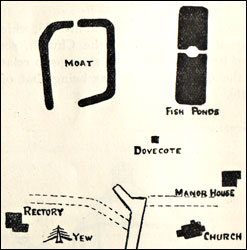

Records of disputes at around this time accuse Richard de Clifford and Adams, the bailiff and under-bailiff of the King’s escheator of selling the timber of the wood in the neighbourhood of Haversham to the value of 21/3 and of destroying the fish pond.

Rolls of the Hundreds 1278 The records of Haversham as a member of the Hundred of Bonestowe show that there were 12 jurors, who declared that “Maud, daughter of Nicholas de Haversam, with the advowson (cum advocatione) of the Church, of the Lord King in Chief by service of one knight’s fee, and is of the honour of Peverel.” There was a list of 46 tenants and their rentals. The average holding was 9 acres (although area measurements varied greatly in those days), paying 13/4 plus services. Appendix C. A DETAILED ACCOUNT OF “ HAVERSHAM” A translation of “Rotuli Hundredorum,” vol. II., p. 346 These are the names of the 12 jurors . . . . who say that Matilda, daughter of Nicholas De Haversam, holds the whole Manor of Haversam entire, with the advowson of the Church, of the Lord King in chief, by the service of one knight’s fee, and is of the honour of Peverel, and pays a rent of 10 shillings per annum to the Lord King, and she has here in demesne 620 acres, of which 234 acres is land held by villein-tenure. Of these Robert al Fispond holds 9 acres of the said villenage, and his service is worth per annum, in works as well as in other obligations and aids 13/4, and he gives “merchet” for his own flesh and blood. (25 other tenants named) each of whom are holds 9 acres of the same sort of service as Robert ad Fispond. Also John del Aubel holds 9 acres of land freely for his lifetime, and pays a rent to the said Matilda of 13/4 per annum. (5 other tenants named) hold 9 acres of the same land by the same service. Also Walter Bending holds 5 acres from the same lady and pays 6/8 per annum Also Galfr’ Molindinar’ holds 18 acres with the mill from the same lady and paints 113/4 per annum. Also the said Matilda, Lady of the Manor, has here free fishing in the water which is called Use. Also the said church of Haversam is endowed with 72 acres of land. Lord John de Haversam hold 90 acres from Baldewin de Belle Aneto and the said Baldwyn holds it from the said Matilda, the tenant in chief, and pays a rent of one pound of cumin per annum and gives as scutage a fourth part of a knight’s fee. 54 acres of this land is in villein-tenure, of which Henry King holds 9 acres of land, and he pays per annum in work and aids to the value of 13/4, and gives “merchet” for his flesh and blood. (5 other Tenants named) each of whom are holds in that place 9 acres of land by the same sort of service as the said Henry King performs. Also Robert Faber holds one messuage and half an acre of land from the said Lord John freely, and pays him 4/- per annum. Also Henry Wynegos holds from the said John 18 acres freely, and pays him 1d. per annum. Also Simon le Rus holes from the said John 16 acres freely, and pays him 4/- per annum, with small (? plots) freely to his tenants. Also Thomas de Britannia (i.e., Brittany) holds 24 acres of land freely, and pays annually 4d. and one pound of cumin to the tenant in chief, and 1d. to Lord John de Haversam. Also (he pays) 9/-, to God and to the Church of the Blessed Mary of Haversam for the maintenance of the lights (i.e., candles). Also John Molondinar’ holds from the said Thomas 6 acres freely, and pays him annually 9/1., and (pays) 2/- to God and the Church. Also John Aubel holds 6 acres freely from the said Thomas and pace in annually 1d., and (he pays) 2/- to God and to the Church for the maintenance of the lights. Notes: An acre was originally an open ploughed or sowed field, excluding woodland and waste land, and it was not a legally defined measure of surface area until 1357. The actual area of the above “ccccc & xx acres is therefore doubtful. “Merchet” : i.e., Pays a fine to the lord for liberty to give a daughter in marriage. Who was Thomas de Britannia? It would seem that he was probably connected with Lavendon Abbey. There was a John de Britannia who was Earl of Richmond at this time, and Thomas May have been a member of this family. There word Ouse, or Use, is derived from the Cymrie wysg, meaning water. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1289 |

Around 1289 Maud de Haversham married Sir James de la Plaunche, and Queen Eleanor’s wardship ended. This order was issued to the escheator Mast Henry de Bray – Order to deliver to John [error for James] de la Plaunche and Maud de Haversham his wife all the lands whereof Nicholas her father, tenant in chief, was seised at his death, to be held until the King’s arrival in England, so that there may then be done what the King shall cause to be ordained by his council, as the King learns……. that Matilda is of full age.” |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1304 |

In 1304 he obtained licence to crenellate [fortify with embattlements] his dwelling place of Haversham. He may also have constructed the moat at this time, and even possibly built the embattlements on the church tower. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1305 |

Sir James died in 1305, leaving a son and heir, William, aged 5 years, and a daughter Joan. His widow, the Lady Joan, married Sir John de Olney soon afterwards. As Lord of the Manor of Haversham he apparently, with others, namely John de Olneye, John le Hare, Robert de Long, and Nicholas le Someter and a few more, assaulted and imprisoned the Rector of 18 years, William de Ledcomb. De Olney forbade the villagers to give him tithes, fire or water, or to speak to him. He assaulted de Ledcomb’s servants, took away his plough oxen and cattle and starved them till many of them died. De Olney prevented anyone saving the Rector’s hay and corn and depastured the herbage of his meadow. De Ledcomb resigned two years later – no records remain to tell why this dispute happened. Later that year de Olney himself had to raise a complaint about a breach of the park at Haversham by some miscreant. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1314 |

In 1314 Sir John de Olney lodged a claim on behalf of his wife, Lady Maud, to the manor of Little Linford, stating that her grandfather, Hugh de Haversham, had held it in the days of King John. In 1325, after de Olney’s death, it was found that he held Haversham and Compton Chamberlayne jointly with his wife Maud, and also lands in Hardmead, and the manor of Linford Parva. Little Linford had come to him on the death of Thomas de Hautville “who had mortgaged the same to the said John for a certain sum of money which he ought to have paid by the feast of St Michael last, before which day the said John died.” However, the overlord John de Somery intervened and seized Little Linford for himself, so that neither the de la Plaunche nor the de Olney family were able to keep it. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1329 | Sir William de la Plaunche, who married:- (1) Elizabeth, dau. of Sir John Hillary, Chief Justice of Common Pleas; (2) Hawise. When Lady Maud died around 1329, she left her children William and Joan de la Plaunche and a son John de Olney. William died aged 34 in 1335 and his son, also called William de la Plaunche died at only 21 years old in 1347. Inquisitions held at their deaths give us further clues. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

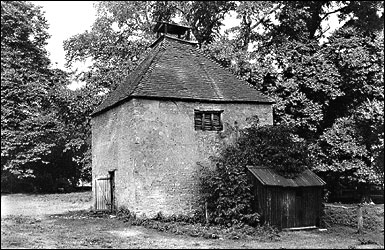

| 1335 | Sir William de la Plaunche, his son, aged 10. Roger Hillary and John Legge, guardians. In 1345 Brothers Stephen de Haversham and Roger de Bermyngham were fellow canons of the subprior and convent of the conventual church of Kenilleworth. Inquisition 1335 Hawis, widow of the first William de la Plaunche gave her oath no to remarry without the King’s licence and was granted a dower of “the great chamber with the chapel at the head of it beyond the door of the hall, the maids’ chamber with the gallery leading from the hall to the great chamber, the said door into the hall to be shut at the will of Hawis; also the painted chamber next to the great chamber, with a wardrobe; a dairy house with the space between the dairy and the door into the great kitchen, which door could be shut at Hawis’ pleasure; the new stable with the house called the cart-house; a grange called the Kulnhouse; a third part of the dovecote &c.” |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1342 |

In 1342 Hawis was awarded £4 for livery and the advowson of the Church of Bereford St Martin in Wiltshire by the King. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1347 | Katherine, his daughter, aged 4; married William de Birmingham. Inquisition 1347 Elizabeth, widow of the second William de la Plaunche, was granted her “reasonable dower of the lands”, namely “A third part of two parts of the Manor, including a messuage, a chamber beyond the gate with solar and houses, and a small close, ….. a third part of the grange towards the Church, and of the adjacent barton, the middle stable, with a small herbarium opposite the door of the hall, and a third part of the orchard with the fishpond there &c.” Elizabeth was left with two children, Katherine, aged five and Joan aged four. A third girl, Elizabeth, was born after her father’s death. Joan died in infancy and the other two inherited – Katherine on her marriage with William de Birmingham, and Elizabeth after her sister died childless some time after 1372. Elizabeth also married a son of Fulk de Birmingham, named John. Before she inherited her ancestral home and all its possessions Elizabeth already held lands in Warwickshire, Staffordshire and Oxfordshire as well as property in London and Southwark. In 1348 Robert de Haversham was appointed with others to arrest all persons prosecuting appeals in derogation of the judgment of the Court of Common Bench. In 1349 Master Richard de Haverisham, treasurer of the Church of Llandaff adjudicated a matter of variance concerning the patronage of a church. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1389 | Elizabeth, a daughter of Sir William de la Plaunche; married Sir John de Birmingham; Lord Grey, d. 1387;

2nd marriage: John, Lord Clinton, d. 1398; 3rd marriage: Sir John Russell. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1416 |

Elizabeth Clinton founded a Guild or College of ten priests at Knoll, or Knowle, in Warwickshire as a “Great Benefactress”, obtaining the King’s licence for this in 1416. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1423 |

Lady Clinton died on 11 September 1423, all her children having predeceased her, and the manor passed to a collateral branch of the original de Havershams. At an Inquisition after her death it was found that Elizabeth held all her vast estates only for life, except a small manor in Haversham called Belney’s.[Belauney] After the death of Lady Clinton the next heir of “Plaunche’s Manor”, with the advowson of Haversham Church, was declared to be William Lucy, “son of Alice, daughter of Margery, daughter of James, son of Joan, sister of William, father of William, father of the aforesaid Elizabeth.” Appendix D. THE WILL OF ELIZABETH, LADY CLINTON. Extracts copied from the Register I of Archbishop Chichele, folio 366; preserved in the Archives of Lambeth. The Will is dated Oct. 29th, 1422, and was proved Nov. 9th 1423. I Elisabeth lady of Clynton hool (1 whole) in mynde the xxix day of Octobr make and ordeigne my testament in this maner. ffirst (2 First) I be whethe (3 bequeath) soule to God almighty, to oure lady Seynt Marye and to al the halwen (4 holy ones, saints) of heven and my body to be beryet in the chauncel of Haversham byfore the ymage of oure lady Seynt Marie. Also I be whethe my new masseboke and my best vestement to the churche of Haversham for to serve at al tymes. Also I be whethe my best chalys and my next best vestement to serve the auter (5 altar) in the chapel of Seynt Petir the apostell in the same church of Haversham there as my chulder lyen. Also I wole that myn executors ordeyn vij prestes to syng for me vij yere next foloyng my deth in the church of Haversham if hit may be that thei may synge in the saide churche and that thei may have esement (6 accomodation) in a place I call Hornes place …. And that ich (7 each) preste of hom (8 them) tak viij marke be yere . . . . and a masse of Requiem be seid every day among hom for my soule, my fader and my moder soules, for all myn husbondes soules, my children soules, for Katerine my suster soule, al myn awncetours, for al the soules that I am in dette to prey fore and for al Cristen soules. Also I be whethe to the frere prechours (9 friars preachers) of Northampton to be departet (10 departed) among hom forto prey for my soule and the soules above said xI s. and to other iij ordres of frerys in the same toune ich hous xx . . . . also to ich prisoner hows in London vj s. viij d. also to ich prisoner hous in Northampton vj s. viij d. Also I be whethe to the making of the belles of Haversham x marke. Also I be whethe to the priour and the convent (11 convent, a religious community) of Maxstoke to prey for my soule and the soule of my lorde of Clynton xI s. Also I be whethe to be departet amonge my pore tenantes of Haversham x marke to prey for my soule, and to be departed among my pore tenantes of Compton Chamberleyn xI s., and to my pore tenantes of Cloybroke xx s. . . . . Also I be whethe to Alys Payn, of sche (12 she) be with me in to my last ende c marks, or ells (13 else) the valew of goode as muche as hit wul conteyne. . . . . Also I be whethe to the abbot and the covent of Notley to prey for my soule, mu moder saule and the soules abofe write x make. Also her or her I be whether to Elsabeth the wif of George Longvile my lesse sauter and my best goune to have me in hir remembrance. Also I be whethe to Sir John Marscall person (14 parson) of Lynford to prey for my soule xI s. Also I be whethe iche swyer (15 squire) that is with me in household at my deyng xI. s. . . . . to Jankyn Boteler xI s. and to ich other yoman that is with me at my deying xx s., and to ich grome xllj s. iiij d. . . . . (seven executors named) And for to execute this testament truly and to perfourme my wille the her I be whethe to John Barton xx Ii., to Thomas Payn x marke and to Sir Gilbert Thornbern person of Haversham her herc s. . . . . For to fulfil my foresaid testament as thei al wul unsware afore God at the dreadful day of dome. Some places and persons mentioned:- Maxtoke, in Warwickshire, the seat of Lord Clinton. Compton Chamberleyn, in Wiltshire. Claybroke, in Leicestershire. Nutley Abbey, of Crendon Park, a few miles west of Aylesbury. Thomas Payn, the husband of Alice Payn; see brass in the Chancel. . Gilbert Thornburn, the Rector from 1400 to 1427 John Marscall, the Rector of Great Linford from 1393. Isobel de Olney, descended from a second son of Maud de Haversham, great grand daughter of Sir John de Olney and married to Walter Strickland, an armiger [holder of heraldic arms], contested the claim. At her death she was in possession of all the estates belonging to the old de Haversham family, namely Haversham Manor, two parts of Cleybroke in Leicestershire, Compton Chamberleyn Manor and other lands in Wiltshire. Both Cleybroke and Compton Chamberleyn had come to be called “Lady Clynton” manors. Isobel’s son Richard, inherited these lands aged only 13 years, and in 1457 the estates came into the undisputed possession of Sir William Lucy, the descendant of Joan, daughter of the Lady Maud.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1444 | Richard Strickland, her son, aged 13 years, grandson of Joan, the daughter of Lady Maud and Sir James de la Plaunche. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1457 |

Sir William Lucy, of Charlcote, a great-great-grandson of Joan, the daughter of Lady Maud and Sir James de la Plaunche. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1466 | Sir William Lucy. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1491 | Edmund Lucy. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1497 | Sir Thomas Lucy. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1525 | William Lucy. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1551 | Sir Thomas Lucy, described in 1572 as "of Harsham, alias Haversham." | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1600 | Sir Thomas Lucy. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1605 | Sir Thomas Lucy, who was succeeded by 3 sons in turn. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1640 | Spencer Lucy died 1663 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1653 | Robert Lucy died 1660 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1660 |

Richard Lucy was “running much in debt and deeply mortgaging his demesnes here, did in conjunction with one Currance, the mortgagee a London Tailor, I am informed, Anno 1664, convey this estate to one Maurice Thompson.” We are not told who the informant was. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1664 |

Maurice Thompson purchased the Haversham estate in 1664 despite being “a person of mean extraction.” His leanings were towards Cromwell’s government and he was also said to have been an East India merchant. In 1665 he restored the ancient dovecote, and an inscription on the Clinton monument tells us that it too was restored in the same year by his wife. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1671 |

Arms or a fesse dancetty azure with a 3 star argent threreon and a quarter azure charged with a sun or. In 1671 Maurice died and his son John Thompson succeeded him, having already served a term as Sheriff of the County of Buckingham. He was created Baron Haversham of Haversham in 1696 and in 1702 became Lord of the Admiralty. His first wife, Lady Annersley, daughter of the Earl of Anglesey, had died in 1704 and is buried in the vault under the chapel floor at Haversham. In Parliament John Thompson was known for strong attacks on the Tories, including the case of the impeachment of Somers. Despite this, Thompson changed sides and became a Tory during the days of Queen Anne, when the Whigs “drove at Schemes he could not down with.” After a short illness Lord Haversham died at Richmond on 1 November 1710 and he was buried in the church there. Appendix F. EXTRACTS FROM THE SPEECH OF LORD HAVERSHAM, Dec., 1703, AGAINST THE Bill to prevent occasional conformity. I shall not, my Lords enter into the Consideration of the Justice or Injustice of this Bill, whether a Man may be depriv’d of what he has a Legal Right to, without a f there Forfeiture on his Part. Tho’ in my Opinion he may, because private Right is always to give Way to publick Safety; and nothing else can justify one of the Best Bills that ever was made for the Security of the Protestant Religion, I mean the Test Act. But this is not the Case here; the persons affected by this Bill are such as have been always serviceable to the Government, and are some of the best Friends to it . . . . In the next Place, my Lords, what heavy Taxes lie upon us here at Home, without any Hope of Ease, and very little Expectation of Advantage. The Reason why Men cheerfully undergo such Burthens is, because they expect some publick Advantage by them, or at least, that enjoy he the Remainder of this Security: . . . . We have, my Lords, given great Sums the last Year for the Army; but what great Matter have we done? And as to our Navy what a vast and fruitless Expence we have been at? I confess to your Lordships when I consider at these two Heads, it put me in mind of Old Jacob’s Prophesy of his Son Issachar, in the 14th Chapter of Genesis; Memoirs of Lord Haversham, 1711, pp. 2-5. Appendix G. Extracts from the speech “upon the State of the Nation,” by Lord Haversham in Nov., 1705, in which he appealed for the sending of an invitation to the Heir-Presumptive; Her Majesty, Queen Anne, being present. My Lords, . . . . Being conscious to my self of a Heart felt Loyalty and Duty to her Majesty, and Zeal for her service, as is possible for any Subject to have; and knowing that the best way of preserving Liberty of Speech in Parliament is to make use of it, I will mention Three or Four General Heads to your Lordships and speak to them with a great deal of Freedom and plainness . . . . (he then spoke at length of “the present Confederate War in which we are engaged ,” and of the “decaying condition of trade.” There is one Thing more, which I take to be of the greatest Importance to us All . . . . ‘Tis the Happiness of England, and that which ever did, and ever will keep the greatest Ministers in Awe; that by the Law and Customs of Parliament, the meanest Member of either House has undoubted Right to debate on any Subject, and to speak his Thoughts with all Freedom, without being liable to be call’d in Question by any Person whatever, till the Parliament itself hath taken Notice of them. This is grounded on the greatest Equity and Reason, because that which concerns All, should be debated by All: Nor is it possible for a Parliament to Debate, or come to a clear Resolution on any Question, or to give Advice to Her Majesty as they ought, without this Freedom . . . . As we enjoy many Blessings under Her Majesty’s happy Government, so I hope we shall have this too, That Her Majesty will never give Ear to any secret or private Information; but as it comes to Her in a Parliamentary way, by the Houses Themselves. The last Thing, my Lords, is that which I take to be of the greatest Concernment to us All, both Queen and People . . . . I think there can be nothing more for the safety of the Queen, for the Preservation of our Constitution, for the Security of the Church, and for the Advantage of us All; than if the Presumptive Heir to the Crown, according to the Act of Settlement, in the Protestant Line, should be here amongst us. ‘Tis very plain, that nothing can be more for the Security of any Throne, than to have a Number of Successors round about it, whose Interest is always to defend the Possessor from any Danger, and prevent any attempt against Him. And would it not be a great Advantage to the Church for the Presumptive Heir to be personally acquainted with the Right Reverend the Prelates? Nay, would it not be an Advantage to all England, that whenever the Successor comes over, He should not bring a Flood of Foreigners along with Him to eat up and devour the Good of the Land? Memoirs of Lord Haversham, 1711, pp.12-17. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1710 |

Their son Maurice succeeded to the title. He was a Page to Sophia, Electress of Hanover. He held the office of Member of Parliament (M.P.) (Whig) for Bletchingley between 1695 and 1698. He held the office of Member of Parliament (M.P.) (Whig) for Gatton between 1698 and 1705. He fought in the siege of Namur, where he was wounded. He succeeded as the 2nd Baron Haversham, of Haversham, co. Buckingham [E., 1696] on 1 November 1710. He succeeded as the 2nd Baronet Thompson, of Haversham, co. Buckingham [E., 1673] on 1 November 1710. He held the office of Treasurer of the Excise from 1717 to 1718. Maurice, Lord Haversham sold the estate for £24,500 to Lucy Knightley in 1728. Maurice died 11 April 1745 in London and was buried 19th April 1745 at Haversham. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1728 | Mr Lucy Knightley of Fawsley in Northamptonshire, “a gentleman of very ancient gentle descent”, bought Haversham Manor from Maurice, Lord Haversham [2nd Baron], in 1728.

His ancestor, Rainald de Knightley, came over with the Conqueror and is mentioned in the Domesday Book. Under Henry VIII Sir Edmund Knightley was one of the chief commissioners for the suppression of the monasteries. In Queen Mary’s reign, Sir Richard Knightley, Sheriff of Northampton, championed the Puritan party, and on signing a petition appealing against the suspension of Puritan ministers in Northamptonshire was fined £10,000 by the Star Chamber and deprived of his position. Sir Richard’s son, also called Richard Knightley, offered his house at Fawsley to John Hampden and his allies as a meeting place when they gathered to plan increasing control of the King. Richard Knightley drew the line at imprisoning and executing King Charles, however, and was himself imprisoned by the Parliamentary Party for his opposition. His son, yet another Richard Knightley, represented Northampton in Cromwell’s Parliament of 1658 and 1659. He was a member of the Council of State who recalled Charles II as King, and was Knighted KB at his coronation. In 1728 Lucy Knightley, descended from the Lucy family of Charlecote, and thence from the Norman de Haversham family, bought Haversham Manor. The Knightleys held Haversham for only three generations. Mr Lucy Knightley died in 1738. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1738 | Valentine Knightley, his son, succeeded him until his death in 1754, having been MP for Northamptonshire from 1748. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1754 | Lucy Knightley was M.P. for Northamptonshire from 1763-1784.

This Lucy Knightley wanted “to inclose several open and common fields” and to take over “certain Glebe lands belonging to the said Rectory, which lie dispersed and intermixed with the lands of the said Lucy Knightley”. He also wanted ”the Tithes now belonging to the said Rectory or Parish Church of Haversham”. To get these privileges he had to obtain Parliamentary approval, which he did with the Inclosure Act of 1764.when he undertook to pay “one clear yearly Rent or sum of £197… to the Rectors of the said Parish Church of Haversham aforesaid for ever”. The lands in question are listed in a document of 1745 at the Lincoln Record Office, signed by the Rector, John Mackerness and the Churchwardens, Thomas Line and Richard Wrenn. In the same document are details of the public roads within the parish boundaries in1745:“And be it further Enacted that there shall at all Times be a publick Road of Forty Feet wide, from a certain Lane at the West End of the Town of Haversham aforesaid, leading towards Stoney Stratford, by the Seven Houses, and by the North side of an old Inclosure called the Pastures to the North West corner of the said Pasture, and from thence over other Part of the said common Fields to the Town Meadow and through and over the said Town Meadow to a certain Bridge called Mead Mill Bridge, across the River Ouse; and that there shall also be a publick Road of Forty Feet wide leading out of the said Road at or near the North West corner of the said old Inclosures, along and over the common ground between the Brook Field and the Middle Field to a Slade called Royal Slade, across the said Royal Slade over Sand Pit Hill and over Stone Bridge Hill to a certain Ford called Long Ford; a Road of Forty Feet wide from a certain Lane leading out of the ancient Inclosures of Haversham, at or near a certain Close called Stonepit Close, along the Ridgeway, to the South East corner of certain old Inclosures within the Parish and Manor of Haversham aforesaid called the Stocking Closes and a certain Wood or Coppice called the Grove, to the South West corner of the same, and from thence over a certain Furlong called the Grove Furlong, to a certain Ford called Short Ford, dividing the Parished of Hanslope and Haversham; a Road of Forty Feet wide from and out of the last mentioned Road at or near the South West Corner of the Grove Furlong by the East Side of Short Ford Furlong, and by the East Side of Two certain Closes called Herbert’s Close and Bushy’s Close into the last mentioned Road leading to Long Ford at or near the Top of Stone Bridge Hill; a Road of Forty Feet wide from the North East End of the Town of Haversham aforesaid, by the North Side of a certain old Inclosure called the Corn Close, to a certain Lane leading into or through other old Inclosures. At a gate near the South West Corner of a close called Stonepit Close, as the same are now staked out.”

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1764 |

Division of the Manor Estate 1764Also in 1764 the Manor, Parish and Advowson of Haversham were bought by the Trustees of Alexander Small, a minor, who also owned the Manors of Hardmead and Clifton Reynes, where he lived. Alexander was described as “a great sportsman” although his behaviour caused “great uneasiness at home.” |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | The second Alexander Small died in 1806 leaving an infant heir, Harry Alexander. The manor estate was sold but the Church advowson was kept for the child so that he might become Rector when he grew up. He became Rector in 1827 and kept Haversham Church and Clifton Reynes until 1850. By this time he had got into debt and was sued for £10,000 and the two parishes were sequestrated by the Bishop of Oxford. Small resigned in 1856. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1806 |

The two Churchwardens of Haversham, William Greaves and Roger Ratcliffe, bought 923 acres of the manor estate in 1806. In 1815 the Manor portion of the estate, of 563 acres, was assigned to William Greaves for £15,500 and the Mill section, of 360 acres, went to Roger Ratcliffe for £6,000. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1815 | The Manor and 503 acres assigned to Wm. Greaves for £15,500; the Mill and 360 acres assigned to Roger Ratcliffe for £6,000. On the death of Wm. Greaves in 1816, without children, the estate was further divided, and the reduced Manor portion was vested in his brother:- | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1817 | Two years later, in 1817 William Greaves died, and his brother Thomas Greaves inherited part of the remaining Manor property while Field Farm, later known as the Brook Field, went to a younger brother James. Thomas Greaves continued to own the Manor until he died in 1826. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1826 | Edmund Greaves, his son inherited. He held the Manor until his death in 1867 and then Edmund’s nephew, Rev John Albert Greave | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1867 | John Albert Greaves, Edmund's nephew, Vicar of Towcester, and afterwards Rector of Great Leighs, Essex. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1893 | Thomas Guy Greaves and others who sold it for £12,500 to Henry Thomas Shaw. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1919 | Henry Thomas Shaw, then sold it for £11,000 to Price Jones. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1926 | Price Jones, again sold it for £7,000 to Colonel Edwin H. Pickwoad. C.M.G. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1928 | Colonel Edwin H. Pickwoad. C.M.G. Died in London, and the estate sold for £3,150 to Alfred Giles O. Randall. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1932 | Alfred Giles O. Randall | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1936 | Giles and Alice Randall bought the Manor c.1936

Appendix H. LANDED PROPRIETORS IN 1936 The total acreage of the parish is officially given as 1,634 acres

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1944 | The orignal Manor House burned down, possibly by incendiary bomb. The current house was rebuilt with the Little Manor after 1945. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1906 |

Baronetcy revived 1906Sir Arthur Divett Hayter PC, of Bracknell, Berkshire, inherited a Baronetcy from his father and Linslade Manor from his mother. It is said that his mother gave him Hill Farm in Haversham as a 21st birthday present in 1856. Sir Arthur was a prominent politician. He was Lord of the Treasury from 1880 to 1882 and financial Secretary to the War Office from1882 to 1885. In 1906 he took the title of Baron Haversham, He never lived at Haversham, and when he died in 1918 his Haversham estate, including Hill Farm, Wood Farm, the Mill and cottages was bought by the tenant, John Souster for £11,000. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Manor of Belauney

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1207 |

1775 map In 1207 Benedict de Haversham held a fourth part of a Knight’s fee of 42 acres on the further side of Ernesden and Lauedistoking. By 1226 it was held by Robert de Belauney, who joined with the Lord of the Manor in gifting “the whole woodland of Ernesdene to the Abbey of Lavendon. He also held a small holding in Hanslope. In 1255 his son Richard exchanged this Hanslope land with William Bellany for a holding in Haversham – Belauney Manor. This land was consigned to Hawis, widow of William de la Plaunche by the King in 1342. Belauney did not appear again in the records until 1369, when Walter de Miltecombe renounced his claim on it to Fulk de Birmingham, whose son had married Elizabeth de la Plaunche of Haversham. After Lord Clinton died, Elizabeth married her last husband, Sir John Russell, and he and his heirs inherited Belauney and held it for over fifty years. At Elizabeth’s death in 1423 the Manor was valued at 10s and the whole estate, with 60 acres of arable land and 6 acres of meadow was worth 100s. In 1502 Robert Russell left a manor here worth 10 marks to his son John, aged 8. He sold Belauney to William Lucy, Lord of the Manor of Haversham, in 1533. This little estate is thought to be at the Hanslope end of Haversham near the old Pineham Farm, close to which is a field called “Fulk’s Stockings.” |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Grange

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||