![]()

The contents on this page remain on our website for informational purposes only.

Content on this page will not be reviewed or updated.

|

|

|

|

.

|

||

|

There are many books about the local railways but most seem to fall either into the category of a bias towards ‘techno-speak’,written by railway buffs for railway enthusiasts, or else the potted recollections of selected ex railway employees, cobbled together by community types as ‘social history’.

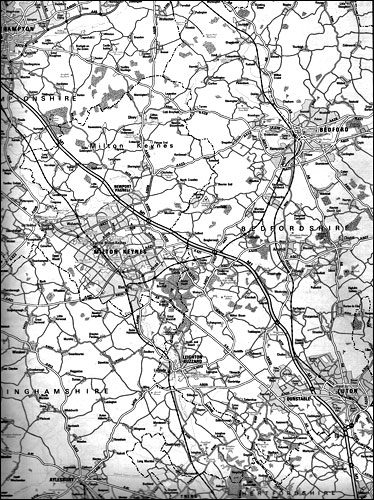

The first ‘railway’ in Britain had been constructed by Sir Francis Willoughby in 1605, as a pit head track built at Wollaton, in Nottinghamshire.However, the first steam powered railway locomotive was built in 1804 by Richard Trevithick, born on April 13th, 1771 and his revolutionary creation proved able to haul 70 people and 10 tons of iron at five m.p.h. The technology was subsequently developed by George Stephenson, a self educated colliery engineman who, in 1821, was then appointed as engineer to the Stockton and Darlington mineral railway. Begun in 1821, the Stockton to Darlington railway, carrying goods and passengers, would be the world’s first public locomotive railway and at the opening of the track in September, 1825 the steam locomotive ‘Active’ pulled the first train along the 27 mile course. On October 6th, 1829 trials then began at Rainhill, near Liverpool, for a locomotive to be used on the Liverpool to Manchester railway and of the five entrants, Stephenson’s Rocket would be the winner. The flourishing economy of the nation, and an increasing investment of capital, soon fostered the popularity of railways and amongst the many suggested schemes would be a line linking London to Birmingham. By the summer of 1830 two routes were being considered and, surveyed by Frances Gibbs, the first proposed a line through Coventry, Rugby and Hemel Hempstead, to terminate at Islington. The other, surveyed by Sir John Rennie, intended a line through Banbury and Oxford and being called in to weigh the relative merits, George and Robert Stephenson eventually recommended the Coventry route, whereupon the two groups then decided to amalgamate, with Robert Stephenson as the engineer in chief. As for George, he wisely insisted on a uniform railway gauge, realising thateventually all the small railways would join up.

The route would initially run from Camden Town and pass through the Tring Gap in the Chilterns but thereafter, due not least to the crossing of the River Ouse, as well as tunneling problems caused by the Northamptonshire uplands, the geographical situation became less certain. Surveying the consequent task, Richard Creed, as the Company Secretary, then decided that the rest of the line to Birmingham would be best laid from Tring to a point slightly north of Aylesbury, and thence via Whitchurch, Winslow, Buckingham and Brackley. However, because of his not insubstantial influencein Parliament, the Duke of Buckingham, being averse to the nuisance of ‘steam and smoke’, thwarted permission for the railway to pass through his land unless via a tunnel but with the cost of this proving prohibitive, a second option had then to be sought. With Robert Stephenson commissioned for the project, by a report dated September 21st, 1831 he recommended a course through Leighton Buzzard, Fenny Stratford, Stony Stratford and Castlethorpe although a later amendment, possibly to accommodate the viaduct across the River Ouse, altered this proposal to pass through Wolverton, instead of Stony Stratford. With this accepted as the established plan, the House of Commons passed a Bill authorising construction of the line in June, 1832 but on a motion by Lord Brownlow it was subsequently rejected by the House of Lords, with an amended Bill being later submitted in October. Following further deliberations, this received Royal Assent on May 6th, 1833, and after two years the scheme eventually became finalised in a series of Parliamentary Acts, in fact this being the same year in which the first passenger rail service on mainland Europe began to operate, from Brussels to Mechelen.

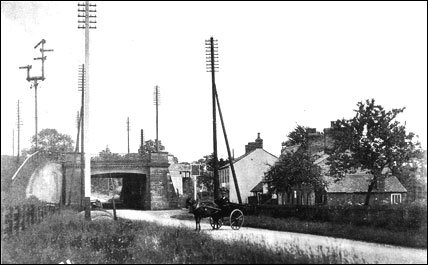

Not least since steam whistles had now beenintroduced, (George Stephenson havingcommissioned a musical instrument maker to design and make a ‘steam trumpet’, first used on the Leicester and Swannington railway in 1832), the benefits of the intended railway were swift to be realised, as evident from this contemporary comment regarding the anticipated progress; ‘Supposing - what, consistently with the results of the whole history of human invention is in the last degree improbable - that the locomotive engines, though now only in their infancy, shall not receive any further improvement, the time of a first-class train from London to Birmingham would be only five hours and a half’. With authority now granted to not only build a viaduct across the River Ouse at Old Wolverton but also a tunnel at Blisworth, proposals were also made to introduce branch lines from Bletchley to Oxford and Bedford, and here the Stephensons shrewdly employed the Parliamentary skills of their friend Sir Harry Verney, who, since 1832, had been the land owning parliamentary representative of Buckingham. As for the actual railway construction, with the necessary land negotiations accomplished by October, 1836 hordes of labourers, or ‘navvies’, were then brought in. The largest labour camp was established at Denbigh Hall, the point where the line crossed the Watling Street, and the site would become a temporary terminus until the completion of both the viaduct over the River Ouse and the Kilsby tunnel. Then despite the inevitable setbacks, and an understandably fierce opposition from the Canal Company, the track from Euston to Denbigh Hall officially opened on April 9th, 1838 and the arrival of the first train was greeted by all the local children, who ‘broke school’ to witness the event. Teams of horses stabled at the Denbigh Hall Inn, and stagecoaches offloaded from the arriving trains, enabled the alighting passengers to continue their 34 mile four and a half hour journey to Rugby, where they rejoined the rest of the railway, whilst as for the benefit of passengers journeying for other destinations, the railway authorities organised travel by such regular stagecoaches as the ‘Rocket’, bound for Lichfield and Tamworth through Newport Pagnell. Since it was not envisaged that the halt at Denbigh Hall would be a prolonged situation, passenger facilities, for accommodation and sanitation, were accordingly scant and - amidst a sea of mud - consisted mainly of flimsy structures and tents, which sufficed by day as dining space and by night as bedrooms and as a nucleus for all this squalor, at the notorious Denbigh Hall Inn the enterprising landlord, Thomas Holdom, fully exploited the opportunities, and even converted the bar into a parlour, the kitchen into a bar and the stable into a kitchen! Opened with grand celebrations, the entire length of the London to Birmingham railway track was complete by September, 1838 and the continuing need for the Denbigh Hall ‘shanty town’ came thankfully to an end. Yet a plaque to record this unique period of railway history was placed on the south side of the railway bridge in August, 1920 by Sir Herbert and Lady Leon, of Bletchley Park, and the eroded stonework has been the subject of a recent restorative project

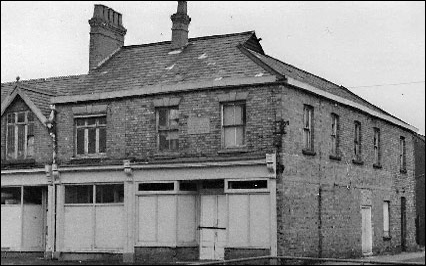

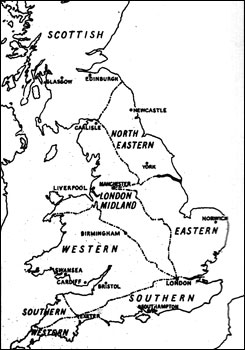

With the opening of the railway, the journey from London to Birmingham could now be accomplished in almost half the time taken by stagecoach, and at two thirds of the price. A mortal success seemed assured but supernatural forces seemed not so pleased, for it was reported that with ghosts ‘of such questionable shape and malevolence’ having cast a spell on certain sections near Wolverton, several policeman employed on the line resigned, rather than continue their duties. Regarding the early conditions of railway travel,comfort seemed somewhat amiss, with an absence of lighting and heating although this would be partly remedied by offering travelers lead containers, heated in boiling water, for 3d or 4d. For second class passengers conditions were further compounded by having to travel in coaches withopen sides, whilst for those traveling in third class, with no seating at all they were packed sixty at a time into roofless wagons - although roofs would be added later by Act of Parliament. As for the railway regulations and penalties, these may be gauged from the London and Birmingham Railway Guide of 1840 which stated, amongst other stipulations, that smoking was strictly prohibited, whilst ‘Any passenger wilfully cutting the Lining, removing or defacing the number Plates, breaking the Windows, or otherwise damaging a Carriage shall be fined Five Pounds’. The second class fare from Bletchley to Euston was priced at 8s 6d for a day ticket and 10s 6d at night, with trains leaving Euston at 8a.m., 2p.m. and 6p.m., on a journey which took two and a quarter hours. Rail travel then received Royal approval in 1842, when Queen Victoria made her first train journey on the line between Slough to Paddington, this being the same track that in the same year accommodated the first railway telegraph system. In 1846 the Cheap Trains Act then laid down that, carrying passengers at 1d a mile, one train must run daily each way along every railway line but soon the conveyance of freight would overtake passenger traffic, as roads and canals proved increasingly unable to compete with the speed and economy afforded by the growing network of railways. In 1846 the London and Birmingham Railway then merged with a number of northern lines to become the London and North Western Railway and this in turn, much later, became merged with the Midland and 27 other railway companies, to become, in 1921, the London and North Western Railway, the largest of the private railway companies in the world. Apart from that of the railway, the area of Denbigh Hall long had an historical, if somewhat unsavory, significance, for, as recorded by the famed local diarist, the Reverend William Cole, although before 1700 there were two ‘constables houses’ on the Watling Street - Willow and Denbigh Hall - the former was pulled down in 1706 but as ‘a reputed Bawdy House’, ‘Denbigh Hall alas still stands’! In fact at the beginning of the 18th century mention of ‘Denby Hall’ is made as being situated just south of Rickley Wood, bordered, across the Watling Street, by Squab meadow and two huts, and that the area gained a reputation for dark deeds is hardly surprising for on September 8th, 1617 a report records ‘a stranger slayne and found in Wryckley Wood’. Then on Saturday January 9th, 1741 Edward Sanders and George Foster, a child of about seven years of age, were found murdered in a booth which Sanders had erected, and from which he sold ale and other liquor ‘to Persons that traveled the West Chester Road, contiguous to the Highway just opposite Rickley Wood by a place called Gibbet Close in this parish’. Indeed, near the foot of ‘Wryckley Hill’ Gibbet Close was named from a gallows that until 1699 stood on the site on Bunch Hill, named after a murderer who was executed there in 1654. Continuing this sinister reputation, in 1805 mention is then made of a shoemaker named Burbage, of Simpson, who was murdered on his way to pay his currier’s bill. An early mention of a dwelling as an alehouse occurs - again in Cole’s diary - in 1725, with William Norris recorded as an ‘ale draper’, occupying on the waste a house called ‘Denbigh Hall’. In fact an isolated dwelling had supposedly once stood on the site, inhabited by an old woman named Moll Norris, and according to one story, one wintry night the carriage of the Earl of Denbigh was blocked by heavy snow drifts on the Watling Street. Seeking shelter in the house, after a few days the Earl was able to leave and called for his bill, but misunderstanding his request, Moll, much to the amusement of the Earl, instead fetched him a hatchet which, after paying her well for her hospitality, he then kept as a memento. However, by a variation of this story, according to a letter from the contemporary Earl of Denbigh, published in the Rugby Advertiser of 3rd June, 1909 he claimed that his great, great grandfather Basil, the 6th Earl, had been forced to put up at the Marquis of Granby, as the inn was then supposedly known, when a wheel sheared from his carriage. On receiving commendable service he began to regularly patronise the establishment, whereby the name duly became the Denbigh Hall. Yet whatever the truth, both tales seem rather fanciful, since the 6th Earl was born in 1719 and the inn is mentioned as Denbigh Hall in 1715! Creating a further confusion, when the temporary camp for the navvies was established, a rail guide states that the inn had been recently named the Denbigh Hall by the purchaser, Mr. Calcroft, prior to having been called the Pig and Whistle! Rather more certain is the reputation of Denbigh Hall, having long been infamous as a bawdy house of ill renown, and a regular haunt of highwaymen. In more recent times, after several years of decay, the inn was becoming more prosperous by 1925, due to the increase in motor traffic, and in 1956 acquired a temporary reprieve from closure when, after a representative of the brewery gave reasons why a water supply had not been laid on, Bletchley magistrates granted a renewal of the licence. However, this was on condition that attempts to provide a supply were continued, and the representative confirmed he would be able to obtain a supply at a cost of £656 but this could not be regarded as permanent. If the supply was provided by the Urban Council, then this would incur a cost of £1,100 or, for a one and a half inch pipe, £468, although the latter would not be able to provide enough pressure, or sufficient water. Hinting at an alternative solution, the representative then said that the premises might not always be an inn because, in view of the surrounding developments, the company was investigating other sites on which to provide a public house. In fact the whole question might even prove academic, since with the inn being an old unlicensed house, he wondered if strictly the magistrates had any power to withhold a licence! Finally the matter came to a close on April 4th, 1957 when, containing two guest rooms - each with a Bible - the premises were closed by the Aylesbury Brewery Company, due to a lack of running water. The building was then demolished at the end of the year. HOW LIFE CHANGED FOR THE TOWNSPEOPLE (THE INFLUENCE OF THE RAILWAY AND THE RAILWAY UNIONS) Before 1838 a full battalion traveling along the Watling Street might rest for a night or two in the town but after 1838, with few exceptions, such movements were made by rail, and indeed the speed and convenience of railway travel brought to an end the dominance of the stagecoach. With the declining trade many inns began to suffer, not least at Dropshort Farm, Fenny Stratford, as evidenced by the mention in 1863 of ‘the Farm House, formerly an Inn of importance on the old post road’. Perhaps a more surprising change for the population was the introduction of Standard Time for in the days of the stagecoach, when journeys were measured in terms of days, the fact that the time difference between Yarmouth and Penzance accounted to half an hour was of relatively little consequence. Yet with railway travel, when journey times were brought down to a matter of hours, problems could arise, leading to the need for standardisation. The early timetables thus made an allowance for the time difference, such as 12 noon at Euston equating to seven minutes past noon at Birmingham but in 1880 Parliament then ended the confusion, and instead of each town using ‘sun’ time, the whole country would now set their clocks by Greenwich Mean Time.

The Industrial Revolution had lead to a migration from the countryside of agricultural workers seeking employment in the developing towns, including jobs on the railway but ‘what the ultimate effect of this change on the nation will be has yet to be seen; but some prophesy as a result stunted bodies and shallow and excitable minds’. No doubt anyone sufficiently courageous to venture along Queensway, in Bletchley, late on a Friday evening will be able to verify the accuracy of this foresight. The opening of the London to Birmingham railway line had lead to the introduction of a daily milk train which, taking milk and butter to Watford and London, was partly responsible for the change from sheep to dairy farming in the region. Also, the railways now brought cheap American wheat to those areas previously dependent on home grown produce and with this contributing to the agricultural depression, even more farm workers now began to seek employment in the towns or, regarding the more adventurous, left for opportunities overseas. As for Bletchley, for the established residents perhaps housing developments, to accommodate the workers on the railway, were the first indication of the local changes becoming apparent and principally due to the difficulty of providing homes for their branch line staff, in 1853 the L.N.W.R. built Railway Terrace, which then stood in relative isolation amidst the open farmland that separated Fenny Stratford from Bletchley. The terrace was variously known as Drivers Row and Company Row and being of an enhanced size, the first house, with an extra window, was supposedly reserved for the equally enhanced status of the Shed Foreman. (The Row was demolished by B.U.D.C. in 1972). New houses were also being built in Bletchley Road and in one of the first, which later became the bookshop of W.H. Smith, for four years lived Mr. Fennell, who in 1870 was appointed as the foreman of the carriage and wagon department at Bletchley, a position he would hold for over 40 years. In order to exploit the custom brought by anincreasing number of railway passengers, Robert Holdom had the Park Hotel built in 1870 and from around 1875 until the end of the century, by the enterprise of a Fenny Stratford brewer and a Leighton Buzzard solicitor, streets were laid out from Duncombe Street to Cambridge Street, on the land adjoining the station.

Largely due to the railway influence, in Park Street a shop for the Bletchley Co-operative Society opened in February, 1884. Indeed railway men were the pioneers of the Society, including Joseph Fennell, son of the previously mentioned Mr. Fennell, who had joined the railway as a junior clerk in the telegraph office, of which he eventually became the head. A keen sportsman, at the beginnings of the local Co-op Society he was one day fetched from the cricket field to carve up the first animal received by the butchery department, since no professional butcher was available! With the seal being appropriately that of a little locomotive named Unity, the first meeting to form the Bletchley Co-operative Society had been held on December 10th, 1883 at Bletchley Station with Thomas Simmonds, a railwayman, elected as President. Unfortunately, however, he only occupied the position for a short while, being tragically killed on December 29th in a shunting accident at the station.

Despite the increasing growth of the town, street lighting remained inadequate and amongst other business, in September, 1886 a Vestry meeting at the Bull was called to appoint a lighting inspector, with a scarcity of lamps especially noted in Park Street, Albert Street and Oxford Street. It was therefore resolved that £140 should be allowed for lighting expenses during the coming year. Continuing the housing developments, in August, 1887 freehold pasture land, near Bletchley church, was sold by auction at the Swan Hotel and also sold, on the orders of Mrs. Duncan Sanders, were two plots of valuable building land almost adjacent to the Park Hotel, abutting onto the main road. For 2s 2d a yard, they would be purchased by Superintendent Hall, of Fenny Stratford. Yet sanitary conditions were not keeping pace with the increasing developments, and disease often claimed many lives. The introduction of the railways also brought the potential for other hazards and one occasion would occur in May, 1887 when, accompanied by his son, Mr. Cecil Peake, of Stoke Lodge, drove a light waggonette to Bletchley Station to meet Mrs. and Miss Sinkins, who had travelled by train from the north to stay with them for a while. Whilst the party were riding from the booking office along the Railway Company road, a train leaving the station suddenly startled the horse which, taking fright, then galloped away, overturning the carriage. With the occupants thrown from their convyance, Dr. McGachen swiftly attended the casualties at the scene, and sent them to the Park Hotel. In a more beneficial influence, the railway brought enhanced opportunities for trade and amongst those swift to take advantage was Thomas Wodham, who delivered coal to order from Fenny Stratford station, being also the agent for ‘Proctor and Rylands prepared Bone and Special Manures’. As for G.J. Riddy and Sons of the High Street - ‘game, fish and poultry dealer’ - they could now offer ‘fresh arrivals daily’ of oysters. Despite the opportunities of railway employment,some townspeople were nevertheless seeking opportunities elsewhere and in 1888 John Steele, formerly of the railway engineering department, emigrated with his family to Queensland, Australia. With his effects to be auctioned, Mr. F. Sear, a coachbuilder with premises near to Bletchley Station, was also leaving the district whilst as for Mr. Wallace Parmeter, on relinquishing the occupancy of his farm near the railway station, the 42 head of excellent shorthorn cattle, carthorses, lambs and farming implements were all to be sold on the premises. In view of the increased housing, in 1888 improvements were scheduled along Bletchley Road, from the railway bridge to Park Street but although the authorities at Aylesbury had promised that Bletchley Road, now in a pronounced state of disrepair, would be ‘well and truly made up’, this was not immediately forthcoming. Yet the area still proved attractive to developers and in 1892 ‘The Brooklands’ Building Estate, ‘5 minutes walk from Bletchley Station’, offered four new semi detached houses - ‘brick and slate’ ‘Freehold and Land Tax redeemed’, as well as 25 plots of freehold building land, some facing the main road to Bletchley. The rest, situated in Brooklands Road and Westfield Road, would be sold by the firm of George Wigley on Thursday, June 16th at the Bull and perhaps for the benefit of both residents and travelers, in 1893 an amended plan was received from Mr. Bailey for a temperance hotel, baths etc. in Albert Street.

In order to lessen the burden of rates, the County Council was now to be asked for a subsidy to maintain the main roads, a request that was reinforced by the local council possessing a right to declare all roads leading to railway stations as main roads. Included within this category were the Watling Street and Bletchley Road, and along the latter granite kerbing had now been laid, with the stretch from Cambridge Street to Victoria Road paved on the north side. Railwaymen now occupied much of the housing around the station, and John Bryant, a platelayer with the L.N.W.R., had moved to Duncombe Street on the occasion of his marriage. In 1902 he then had his own house built on the opposite side of the road, at a time when the ‘better type’ of cottage at Bletchley was being sold for about £100, or let at 5s a week. Apart from highways and housing, the railway also influenced a need for new centres of social activity, and the workingmen’s club provided a welcome example, with alleged origins from the experience of Arthur Phillips, a ticket collector, and George Bowler, an engine driver, who one evening had been unable to find a seat in a local pub! There and then they decided that the railwaymen should have their own facility and in 1909 the ‘Bletchley and Fenny Stratford Club’ was duly begun in a small cottage in Park Street. In time, provision was made of the more commodious ‘Railway Institute’, (in fact a green corrugated iron hut built on railway land near a row of lock-up shops in Bletchley Road), and amongst the facilities was included a billiards table. As for other uses, the hut would also accommodate Mutual Improvement Classes. For many years, from 1937 Ernest Perkins would be the secretary and for voluntarily helping many railwaymen to brush up on their knowledge - very necessary to pass their exams - he even held evening classes at his home, 5, Church Green Road with such commitment rewarded in 1967, when he received the B.E.M. A native of Northampton, he had come to Bletchley at the age of ten and on leaving the Bletchley Road schools in 1913, he then worked on a bookstall for a year. He joined the railways at Willesden on Armistice Day, 1918 as an engine cleaner and a year later transferred to Bletchley. Made a fireman in 1926, he passed as a driver in 1937 and took up this occupation in 1941, becoming a driver instructor in 1956. As for the ‘Railway Institute’, this, and the neighbouring shops, were eventually demolished at the construction of the Flyover but the ghost of the Institute lingered on for with the building having been used by the St. John Ambulance Brigade, on the premises they kept a wired skeleton, of real bones, seated in a wheelchair. At the demolition of the Institute, this was then stored in the old post office building and forgotten, until two boys, from Bletchley Grammar School, one day spied through the keyhole and thoroughly startled by the sight, swiftly informed a disbelieving policeman! By an advert in a national paper of 1910, the town’s railway status was brought to a wider audience, with land being offered at ‘25 pounds an acre: Bucks, one mile Bletchley junction, L.N.W.R., near market town. 91 acres freehold land on south slope, 15 acres fertile arable, rest good pasture..... Railway siding. Stonebridge and Foll, Auctioneers’. Indeed, railway life was now bringing new features to the town with regular Orphan Fund Parades, Hospital Sundays and occasional Church Parades, at which would be proudly carried the banner of the Bletchley Branch of the Associated Society of Railway Servants, the centrepiece being a picture of Bletchley station, looking north from the Bletchley Road railway bridge. The banner had been purchased from the London factory of George Tutill and before a proud gathering of railwaymen, wives and the public, had first been unfurled on Good Friday, 1900, by Richard Bell, the General Secretary of the A.S.R.S. Strikes also became a new feature of the town, with the first National Railway Strike taking place in 1911. The combination Act of 1800 had banned any artisan from organising a strike or joining a trade union but this was repealed in 1825 and following a long, hot, summer, the harsh railway disciplines were now brought to a head, the four national unions, the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants, the General Workers Union, the United Pointsmen and Signalmen’s Society and the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen, calling their men out on strike in August - ‘loyalty to each other means victory’. However, with most of the men reluctant to strike, fearful of losing their jobs, Allen Wells, a driver, was the only Bletchley man to heed the call and by Sunday, August 20th the strike was over. By the terms of the settlement there was to be no victimisation, and each man who stayed at work received a golden sovereign, almost a week’s wages. As for the unions, they produced a medal inscribed ‘Railway Strike 1911 loyalty to one another’, which was perhaps a sentiment best applied to Allen Wells. Born in Loughton, he moved with his family to Old Bletchley in 1881 and becoming a member of the A.S.R.S. in 1897, after a while at Walsall, where he joined the Labour League, he then came back to Bletchley. In 1904 he had been one of the men who met railway officials to try and obtain better working conditions and after working for a time at Oxford, he came back to Bletchley in 1909, being nominated as his trade union delegate at the annual meetings in 1910 and 1911. As assistant secretary to the A.S.R.S., of which his brother, Oliver, was secretary, he enrolled many new members in the union which, on ceasing to exist on March 29th 1912, through amalgamation with two smaller unions, then became the National Union of Railwaymen. As one associate would recall, ‘I remember him, of course, as a ball of fire concerned only with the welfare of the less fortunate and one is glad to know that he lived long enough to see som any of his hopes fulfilled’. As for his brother, Oliver, at the age of 17 he had been elected to the Bletchley committee of the U.K. Railway Temperance Union which, apart from running the activities of the Society ran a library at the Coffee Tavern. Four years before joining the Motive Power Department of the railway, Oliver had been employed at local nurseries, where the central premises of the Bletchley Co-op Society would later stand but having then become a fireman on the railway; in 1899 in a tragic accident at Burton on Trent he lost the lower part of both his legs. In 1900 he then began in business as a shoemaker, a family trade, in Duncombe Street and during the year was made treasurer of the Mutual Coal Society, being associated with the committee until 1911, when the Society merged with the Bletchley Co-op. In fact in 1921 he then secured a job as a clerk in the Co-op Society’s office and in 1930, (his first attempt having been in 1908), he was elected as a member of the Council. A member of the new National Union of Railwaymen would be Harry Dimmock, of 1, Bedford Street who in 1914 was the first railwayman - and the first Labour member - to be elected to the Urban District Council. Born in 1884 in Denmark Street, (then known as New Street), as a boy he had been apprenticed to Henry Gilbey, a draper in Aylesbury Street but in 1900 he began an apprenticeship in the brick laying section of the railway, marrying Miss Garner of Walnut TreeCottage, Old Bletchley. He then became Vice Chairman of the Council in 1919, the year in which during a further railway strike the sympathetic local Reverend John Firminger led the local procession along Bletchley Road. As for those of opposite sympathies, Charles Lake blacklegged the strikers and drove a train from Bletchley to Euston. An engineer and author of many books on railway matters, in his later years he lived at Bow Brickhill and there he lies buried in the churchyard, having lived from 1872 until 1942. In fact his widow continued to live in the village until about 1945 and died, aged 79, at Bath hospital in 1953. By their strike, the railwaymen would succeed in securing an eight hour day, and perhaps in celebration in 1920 a new and colourful silk railway banner was placed on order, emblazoned in gold with the letters N.U.R. However, when placed on display in the branch meeting room at the Park Hotel, it was then noticed that the neckerchiefs, worn by the platelayers in the foreground of the embroidered centrepiece, were the wrong colour and the banner had to be returned to the manufacturer for the erroneous areas to be rerendered in red! As for the previous banner, this was carried for the last time on Sunday, 15th June 1920, when a gathering of railwaymen met near the Bletchley Road railway bridge to begin a procession to Leon Recreation ground, headed by the Station Band. The old banner was then furled and stored in a box, with the new and now amended banner taking its place. Other banners to be carried at N.U.R. events, as well as on other occasions, such as Hospital Days, were those of the ‘Court Perserverance No. 8538 of the Ancient Order of Foresters’ and of the ‘Band of Hope Lodge No. 803 of the National Independent Order of Oddfellows Fenny Stratford’. Each banner - the Foresters being of green silk, and the Oddfellows of blue silk - were ten feet square and had their emblems painted on either side in oils. That of the Foresters depicted a sick bed scene with the motto ‘Help in time of need’, whilst the Oddfellows featured two generations, a man and a boy. With around 400 members, in 1908 the Foresters had their headquarters at the Maltsters Arms, Aylesbury Street, whilst the Oddfellows, with a membership of 140, and 86 in the juvenile branch, met at the Bull and Butcher, on the other side of the street! In 1922, at a packed assembly in St. Martin’s Hall Councillor Dimmock, on behalf of the railwaymen, made a farewell presentation to the railwaymen’s friend, the Reverend Firminger, who was now leaving the district and in a move of which the Reverend would have approved, also during the year in view of the recent strike the L.N.W.R. set up local Departmental Committees, to improve relations between employees and management. At Bletchley a ‘Loco and Traffic Committee’ was duly established, and such committees would then form part of a system allowing disputes to be raised at various levels, leading finally to the National Wages Board. Of the more substantial type, new housing in the town was now made possible by the increased salaries of people commuting to London, the average journey time now being 1 hour 45 minutes, or an hour with the non stop service. Starting from 03.45 there were 22 services on weekdays and the Council had asked the L.M.S. to grant cheap fares from Bletchley to Euston on Saturday, as well as Wednesday, each week. In fact recently changed from Tuesday, Wednesday was the early closing day at Leighton Buzzard, where cheap fares were already being advertised. However, actually getting to Bletchley station could be a challenge and the attention of the Council was now drawn to the very bad condition of Bletchley Road. In consequence the County Surveyor promised to attend to the footpath but due to the planned installation of a water mains, to run from the river bridge on the Watling Street, across the Yard End allotments, via Cambridge Street, and on to Old Bletchley, for the moment all other work would be subject to delays. Delays were also suffered from Sunday, January 20th 1924, when a nine day strike was held by A.S.L.E.F. One member of the strike committee would be Mr. H. Souster, who having begun his career on the railways as an engine cleaner, then progressed from fireman to driver, both on the main and the branch lines. However, perhaps now little concerned with strikes, or their consequence, was George Missenden, one of the oldest drivers of the L.M.S., who in September retired at the age of 70, after 53 years in railway service. In November, 1924 a special meeting was called at the Railwaymen’s Institute, in Bletchley Road, to consider how best to carry on in the face of a debt of £18. Never very successful, the Institute had been greatly affected by the rival attractions, to include billiards, which were being offered at the recently opened Social Centre, at St. Martin’s Hall, and it was perhaps therefore ironic that in early 1926 at St. Martin’s Hall Alderman Dobbie of York, President of the National Union of Railwaymen, would address a large gathering. During the 1926 General Strike, lasting from May 3rd to 13th, each day the new railway banner was carried at the end of the protest procession, accompanied by the Station Band. Each afternoon, with sides picked from the various departments, a football match was then played in the grounds of Bletchley Sports Club and in St. Martin’s Hall concerts were held nightly. With their headquarters situated in the Co-op Hall, from the three railway unions members had formed a local Committee and traveling around on a motorcycle on their behalf was Mr. A. Felce who having been early employed as a bricklayer by Alf Taylor, then joined the railway and was twice wounded when serving with the Devons during World War One. Locally, from the railway workforce of around 500 the strike received a solid support, excepting some six station staff who reported for duty on Tuesday, and a number of volunteers who later manned a few trains. Yet the strike soon crumbled and with recriminations from the Railway Managers Association being equally swift, the mood for a nationalisation of the railways unsurprisingly took hold. However, for the future prosperity of the industry this was hardly the time for animosity, and potential business would be forthcoming with a Beet Sugar Factory proposed on a site lying immediately west of the Grand Junction Canal. This would be served by a railway siding which, it wa noted at a meeting of the County Highways Committee, would have to cross the Watling Street. Owned by Charles Janes, of Simpson, in fact the land, situated along the Fenny Stratford, Simpson Road, had been previously known as Scrivens Farm, once held by the late Robert Holdom. With Sid Maycock re-elected as the chairman of the Bletchley branch of the N.U.R., in 1928 the previously mentioned Mr. Felce now became the branch secretary, (a position he would hold until 1938), but with ill feeling still apparent in the aftermath of the General Strike, the need for railway reconciliation was emphasised when in 1934, shortly after their opening, Bletchley Flettons began to transport bricks by road, instead of rail. Not only did this eliminate the risk of damage through shunting but it also overcame the vagaries of a rather less than efficient railway service, which, through this inattention to customer satisfaction, lead to the railway siding of the brickworks declining into disuse. The London Brick Company was also making an increased use of the roads and on February 12th, 1936 formed a transport department with eight lorries, a 20 seater bus and 16 cars. However, the railways then regained their importance with the increased traffic during World War Two but for the railway banner, at the beginning of the conflict it was placed in a box and stored away in a dusty corner of the Co-op Hall, not be retrieved until long after the hostilities had ceased. With the nationalisation of the railways in 1948, many people were thrown out of work but memories of the help and sympathy extended to the railwaymen by the Reverend Firminger, during the earlier years of their union struggles, remained strong and there was a genuine sadness when news arrived of his death in 1949, in a Kingston upon Thames hospital, following a road accident. In 1950, 20% of the Bletchley staff, many of whom were resident in the town, left the railway but nevertheless some 861 people, predominantly members of the National Union of Railwaymen, still locally remained in railway employment and in December, 1950 they had cause to mourn the death of a long standing member, Allen Wells, who died at his home, 38, Albert Street, aged 73. In July, 1951 Mr. A. Felce, of 34, Eaton Avenue, following his second term as branch secretary, (from 1945 until 1951), was amongst the eight delegates chosen by the N.U.R. at a conference in Hastings to visit the U.S.S.R. This was at the invitation of the union of Soviet railwaymen whilst as for British railwaymen, members of the N.U.R. then gained an increase in pay through the effects of a strike in 1953 although this unfortunately alienated members of an alternative railway union. However, perhaps these frustrations could then be allayed by the decision to form a local branch of the British Railways London Midland Region Staff Association, whose objectives were to provide social and recreational facilities for railwaymen, their wives, dependents and children. Otherwise relations could perhaps be smoothed by a visit to Central Gardens, where the Council had given permission for a track to be set up, but only for one day, as an experiment by the Bletchley and District Model and Experimental Society. Perhaps instrumental in this decision was Ernest Fryer of 59, Eaton Avenue who, as chairman of the Council in 1952 and 1953, had first been elected in 1948. He would also hold many other offices in the town, in addition to his employment as Chief Clerk at Kings Cross Motive Power Department, to where each day he commuted by rail. A native of North London, he began railway employment as a junior clerk at Camden locomotive shed around 1912, and came to Bletchley in 1930. On recreational matters, members of the N.U.R. regularly attended dances at Wilton Hall but in 1957 they asked the Council to review the arrangements which, stipulating no re-admittance after 10.15p.m., were now deemed out of touch with the modern age, especially by ‘treating the dancers more as irresponsible juveniles’. Since the attendances were falling, it was specifically hoped that the younger councillors would have more of an enlightened outlook, and indeed the following year the restrictions were temporarily lifted. Now with a membership of 700, on February 15th,1960 the Bletchley branch of the N.U.R. had decided to join the national rail strike, and this was not least due to the fact that ‘Inexperienced men are being employed on the Permanent way by means of direct labour at higher rates of pay than the men they are working with’. Yet despite such aggravations, for the many newcomers from the Capital now settling into the ever expanding housing estates the railway provided an essential link with London although some of the recent arrivals seemed less than appreciative of the railway benefits, with complaints now being made by residents on the Grange Estate about the noise from the Oxford branch line. Having been locked away at the beginning of World War Two, in 1962 the railway banner was retrieved from the dusty depths of the Co-op Hall and carried in the Labour Cavalcade to the opening, by Hugh Gaitskell, of the new Labour Hall on June 23rd. The banner then came to prominence again when carried at the protest march in London against the Industrial Relations Act of 1971 and with the occasion being a windy day, a policeman helped to roll it up and so prevent damage to the delicate condition! The next outing was as a stage background at the N.U.R. Centenary Celebration Dinner in 1972 and following a few additional displays, in 1994 it was then stored away at the Milton Keynes Museum of Industry and Rural Life, now known as Milton Keynes Museum. In the Bletchley of more recent times, reminders of the early days of the railway were incorporated into a shopping and commercial centre, built in the town on the site of the old cattle market, and in the naming of the new developments, the names of several pioneering railway engineers were recalled, as in Stanier Square, The Brunel Centre and Stephenson House.

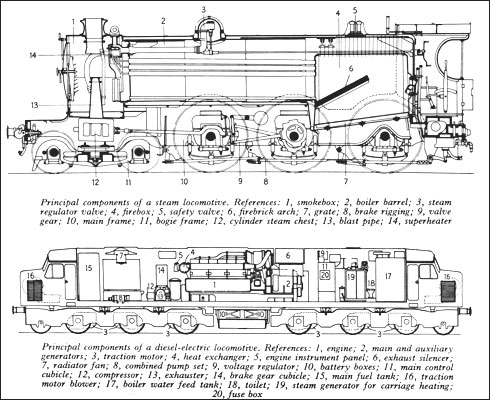

Not least from a plentiful supply of well trained drivers, demobbed from the Services, at the end of the 1940s the railways faced an increasing competition from the roads, and to address this situation the British Transport Report and Modernisation plan, prepared for British Railways, were published in 1955. This proposed replacing steam trains with those of diesel and electric and locally the Oxford to Cambridge line would be used as a freight diversion route, with a flyover to be built at Bletchley to connect with a large new marshalling yard at Swanbourne. This would thereby greatly expand the existing yard, which, in view of the amount of wartime traffic, had been initially built in 1942, complete with an A.R.P. signal box. Albeit a mile or so from Swanbourne station and not in the parish, having a capacity for 660 wagons the complex comprised ten marshalling yards, three reception roads, and 11 storage roads and the new plan was to direct goods traffic to and from the south of Britain by feeding the volumes from the mainline to the proposed new marshalling yard, from where re-routing would be made, so as to cause minimum disruption to the crowded London lines.

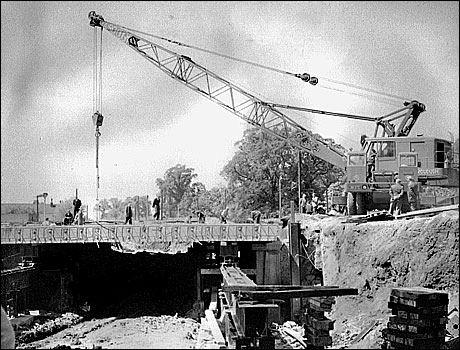

Not everyone was enthused, however, and in January, 1956 for their Tuesday meeting Bletchley councillors met ten minutes earlier to both discuss and vote on a resolution opposing the British Transport Commissions Bill which, now pending in Parliament, included the flyover proposals for Bletchley. After a long debate the councillors then decided by eight votes to one to withdraw their petition but only subject to the Council being granted the right to negotiate - and if necessary at a later stage petition for - a 40 feet bridge span over Water Eaton Road, instead of the 25 feet planned by the Commission. Also the Council held concerns regarding other associated matters, including the amount of property that would be affected in Duncombe Street, the need for improvements to the underbridge in Bletchley Road, and the effect on the North Street housing site and the owners of houses in Tavistock Street. Removing from the Bill the proposal to lengthen the main line bridge over Water Eaton Road, the Commission duly conceded a number of points, and they would also investigate the possibility of widening the branch line on the other side of Tavistock Street. Moreover, with a clearance of 17½ feet above the main line, to allow for the future electrification of the track, the flyover would bebuilt in such a manner as to allow any need for subsequent realignment to the underbridge. Yet however it was aligned, the flyover would bring about the loss of the British Railways Staff Association sports field, by cutting across the ground and so rendering the facility useless for football and cricket matches. With a branch membership of around 350, a new ground had therefore to be sought although with great reluctance in view of the care and attention that had been lavished on the original. However, on a more optimistic note the new club premises were almost ready, and would be officially opened on September 5th. They had been constructed out of the old railway canteen and included a large games room, a smaller committee room, bar and toilet facilities. In August, 1958 a meeting was held between the British Transport Commission, Buckinghamshire County Council, local authorities, landowners, and the N.F.U. to explain the proposals for the new marshalling yard at Swanbourne, and during the following month work then began on the flyover project although to protests from the Bletchley branch of the N.U.R. that inexperienced contract labour was being employed on Sundays. In preparations for the construction of the flyover, two shopkeepers occupying private property had received notice from the railway authorities that they must leave by October 12th and a number of private house owners were also informed that parts of their land would be needed. During the month, since they stood in the direct line of the flyover, the premises of a clothing shop at the corner of Duncombe Street were to be vacated, as also the adjoining café occupied by Mrs. Perrin, and so would come to an end her long established business in the town. In fact it had been almost 21 years since Mrs. Perrin had first opened her café and confectionery shop, (having previously occupied two hutted shops opposite the Park Hotel), and even before then she had been employed for many years as a shop assistant in the town. With her working life now at a close, she would retire to live in a Council house in St. Pauls Road. The first phase of the extensive project, the actual building of the flyover, was undertaken by Faircloughs Ltd. and with the foundations being as deep as the construction was high, the work was scheduled for completion by October, 1959. Contracted to Demolition and Construction Ltd., during that year the second phase, to construct the three approaches to the flyover would then take place over a course of 12 months. Meanwhile, at the Oxford end the new earthworks would extend for about a mile and a half along the present route of the branch line which, slewing out towards the Newfoundout, would have to be widened to allow for the junction with the new flyover line. Also needed would be retaining walls about 500 feet in length, to bring the new line to the flyover abutment. At the Denbigh end, work would begin near the Associated Ethyl laboratories, towards which a large cutting would have to be made. The new line was then to be raised by walls and embankments to a new ‘Skew Bridge’, of pre-stressed concrete, with three large piers, and this would carry the track over the present Bedford branch line to the flyover. At the Cambridge end, work would begin on the Bletchley side of Stag Bridge, (although without causing interference to the Watling Street), but with some two miles of sidings taken up, there was a need for the small bridge over Denbigh Way to be enlarged. Since the flyover approach from the north and east would cover most of the present goods road, a new goods road would be built, passing through one of the arches in a semi circular sweep to the yard. As a consequence of this new arrangement, alterations would make the goods office into a two storey building and alterations would also be made to the shed. With the trader store repositioned, a second one was to be built alongside and a new weighbridge installed. In addition, the several buildings containing the district engineer’s and signal engineer’s offices, workshops and stores would be demolished, and then re-accommodated in a large single storey building. In December, 1959 Bletchley Road was finally spanned by the new flyover when 14 concrete beams, each weighing 22 tons, were lifted into position by a giant mobile crane and the following year the construction was even featured on the front page of the prestigious British Rail publication ‘Transport Age’.

However, progress suffered a setback in early 1960, when a slip occurred of the embankment recently made up near the Newfoundout. Prior to providing the branch line with a new alignment, in previous months thousands of tons of earth and ballast had been used to widen the embankment, and the movement of earth caused a number of derailments including, whilst the train was crossing the main track, that of three goods wagons on the Oxford to Cambridge line. Indeed, it was fortunate that when traveling from Cambridge to Oxford, the derailments had not included the Royal train, which was carrying the Royal party from Sandringham to Romsey for the wedding of Pamela Mountbatten. Not surprisingly, in view of the ongoing construction work, the normal running of the branch lines was occasionally affected and one Sunday in June, 1960 passengers traveling on the Oxford branch had to go by a special bus between Bletchley and Winslow, when the track was closed near the flyover. This was to enable gangers to install a special set of points, plus a short length of track, to link the flyover with the branch line when the flyover was complete and similar work having already been completed at the Denbigh bridge end, for the same reason the Cambridge end would be closed for a day in a few weeks time. At the southern end of the Eight Bells field, in February, 1961 Buckinghamshire County Council then agreed to sell two pieces of land to the British Transport Commission in connection with the flyover project, one piece, amounting to 394 square yards to be authorised by private Act of Parliament, and the other, of 474 square yards, by the County Works Committee. As for the present Bletchley marshalling yard, in view of the proposals for Swanbourne the site would be used as a depot for the stabling and cleaning of diesel and electric trains By now work on the tracks over the flyover was progressing and the contracts for the seven miles of approach work were complete, except for clearing up. The remainder of the work would then be carried out via the railway’s own agencies and with two jobs still needing to be done, these were the provision of a new bridge for the well known ‘Sixty Steps’ near Denbigh Hall and, at the Oxford end, resolving a question of land. After that, the various signalling installations would be determined, before the whole project was then inspected in detail by the Ministry. Supervised by the Bletchley Yardmaster, Dave Siddall, prior to being used by the first revenue earning train, one Sunday in early November, 1961 a dummy run from Swanbourne to Wolverton and back took place by an engine hauling 52 wagons of coal - a weight in excess of 1000 tons - and at various points along the track the train stopped for tests to be conducted. The next day - in fact an hour late due to the presence of thick fog - an operational run by a steam engine hauling 14 wagons of mixed freight from Wellingborough to Swanbourne then passed through, arriving from the Denbigh Hall link over to the Oxford line. In accordance with the official mood, in early 1963 a report by a Ministry of Transport Group then implied a contraction of the existing railway network and as the new Chairman of the Railways Board, Doctor Richard Beeching, Vice President of I.C.I., was tasked to study a reform of the system. At first he had declined the position but having, after several approaches, eventually accepted, he published his ‘Reshaping of British Railways’ report which, as a seven year plan, would significantly reduce the existing network. The Modernisation Plan for the marshalling yard at Swanbourne had not been included in the Beeching Report but nevertheless the scheme was axed, following intentions to now introduce Freightliner trains, in place of the wagon marshalling system. However, since construction was already underway, work on the flyover had to continue, and th structure was finally finished in 1962. In keeping with the original scheme, a great deal of land around Swanbourne had been compulsorily purchased including, then in use as a boarding school for boys, Horwood House, where the well known television gardener, Percy Thrower, had begun his career working under the supervision of his father. In connection with the new yard, Horwood House had been scheduled to became a British Rail training school but instead was now to be sold for a reputed sum of £30,000 to the G.P.O., as a training centre. In February, 1967 it was then announced that the Swanbourne marshalling yard was to close and at a meeting in London, representatives of unions from the Bletchley district were told that although 33 men would become surplus to requirements, they would be offered work elsewhere. Not surprisingly, an N.U.R. spokesman said that ‘The flyover has turned out to be nothing but a white elephant, with only a few trains going over it’ but also unsurprisingly a British Railways spokesman replied that the flyover had proved its use, having been built to segregate freight traffic from the fast main line. Trains were now traveling the main line at 100m.p.h., and without the flyover a freight train crossing from one side to the other might otherwise block four main lines for five minutes or more. Also, a part of the original idea had been to take coal and other freight from the north east and then send it, after remarshalling at Swanbourne, to other destinations. However, since the use of coal as a fuel had now declined, and there had also been a reduction in other traffic, the wartime marshalling yard finally closed in March, 1967 and by early 1971 the rails had been lifted, with only the wartime signalbox remaining. Yet at least for the flyover there would be a partial revival for in the year 2000 Railtrack then announced that they were to reinstate the connections to the flyover, to accommodate engineering trains in use on the West Coast Main Line modernisation scheme. In 1838, with the opening of the completed railway line from London to Birmingham, apart from a milk train halt the ‘shanty town’ at Denbigh Hall thankfully passed into history, and there seemed little immediate need to build a permanent station. This reasoning duly continued until, in 1844, a branch line was proposed from Bedford to Bletchley and following the consequent opening, in November, 1846, during the next year the Bletchley and Fenny Stratford station came into being. Upon completion of the Bletchley to Banbury line in 1850, this station was then enhanced with the status of a junction, and the main station would thereon be known as Bletchley Junction. After the completion of the branch lines, a subway was made and the Bletchley station of 1851 occupied an area of some three acres, with eighty to a hundred men being employed to handle the seventy trains a day. A complete enlargement of the station then took place in 1858 - a ‘big and varied Jacobean’ design by J. Livock - although until 1859 only two main lines, up and down, passed through Bletchley Junction, with a third main line, for goods only, added during the year. Throughout the years, many prominent people would become acquainted with the station and amongst the earliest was Dorothy Pattison, who achieved nursing renown as a civilian counterpart to Florence Nightingale. Escaping an unhappy homelife, Dorothy had successfully applied for the position of schoolmistress at the nearby village of Little Woolstone, and arriving at Bletchley station in 1861, was met there by the Reverend Edward Hill, who drove her to the vicarage at Great Woolstone. There she would stay until the schoolhouse was ready but eventually she left her teaching position and joined the Sisterhood of the Good Samaritan at Coatham, near Redcar, where she became known as ‘Sister Dora’. For passengers, the convenience of railway travel was greatly improved by the introduction in 1871 of the first catering services, whilst as for the wood and galvanised iron Locomotive Shed at Bletchley, by the following year this catered for some twelve engines, with three roads accommodated within the facility. However, burying the engines the shed collapsed in a gale four years later and, surmounted by two gabled roof spans and numerous ducts and chimneys, when rebuilt would measure two hundred and fifty feet in length, with a maximum width of one hundred feet. In 1876 a four track railway line was established between Willesden and Bletchley, a track also being laid from Bletchley to Tring, whilst as for the layout of the station, in a plan of 1878 three roads are shown going through the Locomotive Shed, converging at the southern end alongside the Lodge, opposite the station entrance. Of a date contemporary to the Locomotive Shed and Offices, at the north end of the yard the Lodge, a square two storey brick building, served initially as the clerical office for the Locomotive Shed, but from 1877 until the end of World War Two was then used as a lodging house for enginemen and brakemen. Excepting a space for a chimney stack, a 60,000 gallon water tank took up almost all of the flat roof, with two lines running between the brick piers. Regarding the alterations to Bletchley railway bridge, which was described as ‘a disgrace to the company, a miry nuisance to pedestrians and on account of its narrowness, a danger to the public’, in February, 1880 the parish officers of Fenny Stratford were invited to attend an interview with the directors of the L.N.W.R. However, improvements were soon forthcoming and a rebuilding of the station in 1881 then raised the platform heights, as required for the new trains, and the old subway was replaced by an overbridge. Yet the revised station facilities seemed not to impress everyone and especially not the ‘early traveller’ who one morning in the raw, cold, and foggy conditions ‘peeped into the General Waiting Room of the up-platform, to be regaled with a view of the ashes of yesterday’s fire. I have no word of praise of the management which permits this state of things’. By now the two slow lines north of the station had opened as far as Roade and at this point they diverged towards Northampton. Passenger trains were then allowed to travel on these lines from 1882 and amongst the passengers of national renown would be Mr. Gladstone who, en route to Chester from London, in February, 1887 arrived at Bletchley to meet Mrs. Gladstone, who had arrived from Cambridge.

Before 1887 the Post Office occupied a building at the station near the portico entrance and then moved into new and larger accommodation, built at a right angle to the front. With the old premises taken over by the United Kingdom Railway Temperance Union and the Railway Servants Coffee Tavern Company, accompanied by suitable dignitaries, Richard Moon, the Chairman of the L.N.W.R. performed the opening ceremony on April 18th, 1887 with the outer door adorned with a trophy of signal flags, and the walls decorated with engravings and brightly coloured plates, interspersed with mottoes. Including the use of a harmonium, a large room was provided for reading and recreation, and chess and draughtboards were provided on the tables. The premises also accommodated a ‘comfortable and commodious’ bar, or coffee room, which was provided with abundant tables and seats and ‘every necessary application’ for the supply of coffee and other ‘temperance refreshments’. Initially financed by 200 shares at five shillings each, the Coffee Tavern had been formed by railway workers to provide refreshments and other facilities for railway workers ‘and bone fide visitors’, and all the directors and shareholders were either railway workers or retired railway workers. As for the Temperance Union, they held Bible classes in the Temperance Rooms during the early years but the premises were later used for other purposes, ranging from Railway Improvement Classes to accident enquiries.

Indeed a fatal accident occurred one Thursday in July, 1890 at about 3a.m. when, whilst uncoupling wagons, an employee in the Goods Department, Henry Franklin, was unable to get clear before the engine started to run back. He tried to escape by ducking under the buffers but unfortunately his feet became trapped and although a special train immediately took him to Bedford Infirmary, he died around mid day. The incident proved especially tragic since, having been in Bletchley for around two years, he was soon to be married. By the very nature of railway employment there always the risk of injury and it was therefore perhaps just as well that in January, 1891 at the Temperance Rooms Mrs. Leon presented certificates to the 22 successful candidates of the Ambulance Class, with Bletchley being the only railwaymen’s class in which all the applicants passed. In fact their skills would soon be in need, for around 8.45p.m. one Saturday in January, 1891 a Nuneaton fireman was knocked down by an express train at Bletchley. Suffering a fractured skull, and with an arm broken in two places, he was quickly taken to the home of Tom Smith in Brooklands Road, who had fortunately been one of the successful pupils of the Ambulance Class. During the same month another accident then occurred when, whilst working at the pumping engine on the railway embankment, near the Newfoundout, a railway employee trapped his left hand in machinery, and crushed the end of a finger. The name ‘Newfoundout’ had supposedly arisen when the railway company, on completing excavations to form a loop line, discovered, or ‘found out’, that the curve of the line was too severe to allow the safe passage of trains. The line then had to be abandoned and with the excavation eventually filling with water, it became known as the ‘Newfoundout’. Something else to be found out was the reason why the body of a man came to be laying on the upline, about a mile from Bletchley Station, in June, 1891. His head had been crushed and the left arm broken and in a pocket a second class railway ticket, from Rugby to London, bore the name ‘F.W. Bland Esq., 14, King Street, St. Jame’s, London’.

During many Sundays of 1891, to provide further carriage sidings train loads of waste and chalk from Tring cutting were transported and tipped south of the station, and the year also witnessed a visit by the largest engine then at work on the L.&N.W. Railway, the ‘Greater Britain’, no. 3235, which, with 25 coaches, passed through the station to an enthusiastic reception given by a large crowd of workmen. Replaced by Mr. Finney, of Lord’s Bridge, in April,1892 Mr. Bloxham, the Bletchley stationmaster, transferred to Euston and by this time a Mutual Coal Supply Association had been started at Bletchley station, with Thursday meetings held in Mr. H. Kemp’s Assembly Room, Bletchley Road, for the purpose of taking up shares etc. Towards the close of the 19th century Mr. Trevithick then became the Locomotive Shed Chief at Bletchley. He was the son of the famous FrancisTrevithick who built the ‘Trevy Engine’ which,probably the famous ‘Cornwall’, was built in 1847, rebuilt in 1858, and is now preserved in York Museum. As for the engines which became a familiar sight at Bletchley, the Ramsbottoms’ Problem Class engines, built at Crewe and popularly known as the Lady of the Lake Class, were employed on much of the fast and express work in the Victorian period, an era during which the first all corridor train would run from London to Glasgow in 1897. In 1898 a breakdown train with a 15 ton crane was brought onto the line at Bletchley, and also towards the end of the 19th century a number of ‘Ladies’ were then employed as pilot engines with ‘Bletchley Shed’, now an ‘intermediate Loco Shed’, providing their home depot. Young lads beginning their careers on the railway were employed as call-boys, who would go around the town and ‘knock up’ the engine drivers ready for work. Fred Jarman began as a Bletchley call-boy on October 9th, 1899 at 6s a week and after five years with the fitters, he worked his way through the grades of cleaner, fireman and driver, to eventually retire after 50½ years of service. Succeeding Joseph Dibb, in 1903 James Taberner took charge of the Locomotive Shed and apart from being available to takeover should an express train break down, the ‘Ladies’ were also often employed on the Oxford and Cambridge service. Painted black, as the cheapest form of paint, one emergency they would attend occurred on a Saturday night in March, 1906 when two freight trains collided on the junction just south of the station. A train running by the down home signal had smashed into a train crossing the line and although the drivers and firemen were consequently dismissed, no one was fortunately hurt in the collision. However, during the subsequent operation to clear up the wreckage, when a wagon overturned one of the workmen tragically died from the injuries he received. Much of the debris would be salvaged for scrap, and now also destined for the scrap yard was the last engine of the Lady of the Lake class, probably ‘Mersey’, No. 77. During the same year the Locomotive Shed underwent modernisation, which not least involved the installation of a modern wheel drop operated by hydraulic pressure, developed from two sets of hydraulic pumps, with a 9h.p. Crossley gas engine to power the various machine tools. Nearby, and owned by the L.N.W.R., the Newfoundout served as a water supply for the Locomotive Shed and, cared for by the Company, a number of swans were kept to keep the water free from weeds - the swans no doubt being as concerned as the railway company at the number of small boys unlawfully playing on the railway company raft. In May, 1910 the last of the broad gauge trains in Britain ran from Paddington to Penzance. From thereon all the main lines would be of a standard gauge and of the engines using the main lines at Bletchley, with six in roads, and four outside, by now the Locomotive Shed, (associated with seven small branch line sub depots), accounted for 49 engines, including several 0-6-0 saddle tank engines, (of a type without a cab roof). These were used for shunting, and apart from the pilot engines, a ten ton breakdown crane also stood in readiness. Aspiring to be an engine driver, Costa Wells, a brother of Oliver Wells, had commenced his railway career as a cleaner in the Bletchley locomotive department but in anticipation of his future ambitions, he one day began to drive an unattended engine. Unfortunately, he was unable to stop the locomotive, and it crashed through the closed doors, whereupon Costa’s railway employment also came to a crashing halt. Dismissed, he managed to get a job for a while at Wolverton Works but in 1912 he then decided to emigrate to Canada with his wife, the local union branch providing him with a grant of 30s, for his 12 years membership. At the age of 84 he would die on December 21st, 1964 at Saskatoon, Canada, having been a mill foreman for many years, until his retirement in 1950. As for Bill King, of 24, Cambridge Street, a farrier since 1906 he became the Locomotive Shed blacksmith in 1914. Born in Simpson Road, on leaving school he had been apprenticed to Mr. Garner of Fenny Stratford, and then went as an ‘improver’ to Stony Stratford, before joining the railway at Bletchley. He was married at St. Martin’s church on April 16th, 1912 and his wife also had railway associations, for with her father being an engine driver, the family had moved from Bedford to Bletchley when she was young. When Bill joined the railway there had been eight railway horses at Bletchley, and being trained for shunting work in the station area, the shunt horses were accommodated in stables situated in the Railway Approach Road, with adjoining stables available where passengers could leave their horses when using the trains. At the turn of the 19th century Cecil Hands, the landlord of the George Inn, (in fact his birthplace), had taken over the stables and, before the Post Office acquired their own vehicle, he also delivered the mail to local towns and villages. Cecil would remain as the landlord of the George Inn until 1955, then moving to 5, Clifford Avenue.

On the outbreak of World War One, with, including the office workers, 312 staff employed at Bletchley, unless given permission by the management, railwaymen were not allowed to enlist, due to the increased use of the railways. However, from the telegraph office, having been a member of the Beds. and Bucks. Volunteers Joseph Fennell would serve in the National Guard, whilst Harry Dimmock spent three years at Southern Command Labour Centre. As for Bill King, the Locomotive Shed blacksmith, he bred pigeons for the Government and with the increased rail movements caused by the war, in 1915 Fred Stanton, previously a porter at Bushey, arrived at Bletchley as a fulltime signalman. A native of Willen, he had begun work on the railway at Blisworth in May, 1905. Despite the exemption from military service, life for railwaymen could nevertheless prove hazardous and in 1915, on suffering an accident in the Locomotive Shed Charles Matthews had to have his left leg amputated. Also working in the Locomotive Shed, George Hankins, a fitter, then lost his right thumb and two fingers, when his hand became trapped between an engine wheel and axle box. Then on August 11th, 1916 a soldier and his horse were tragically killed, when a train crashed into a horsebox on the back of a local passenger train, backing out of the Cambridge bay. With Alfred Bowler now as the Lodging House Attendant, ammunition trains could be seen parked in the Bletchley sidings at all hours awaiting despatch. The army guards were housed in one end of a large platelayer’s brick cabin, and by 1917 the Locomotive Shed, accommodating six roads with a turntable fifty feet in diameter, could house some twenty four tender engines, or thirty six tank engines. In spite of the ‘reserved’ nature of railway employment, several Bletchley railway employees did see active service including Risden Lickorish, who was amongst those wounded during the Battle of the Somme. Born at Gayton, Northamptonshire, at 10s a week he had joined the railway as a cleaner at the age of 15, and would return to this employment after his discharge in 1919. Another local railwayman was Fred Healey who, having been taught to drive the petrol electric locomotives, forerunners of the diesel electrics, served with a light railway company of the army in France, working from the normal railheads to the trenches. Born in Salden, he had come to Bletchley with his parents and on leaving school at the age of 13, worked as a blacksmith’s striker for Phillips and Sons, whose premises, in Bletchley Road, would later become the site of the offices for the auctioneers W.S. Johnson. Eventually he found work as a labourer, unloading coal at Bletchley station and before joining the army held a number of cleaning jobs at various locations. Having joined the railway in 1914 as a train reporter, another Bletchley railwayman to see action overseas was William Chappell, who, enlisting in the Royal Engineers in 1917, later transferred to the Lancashire Fusiliers. Resuming his railway career after the war, resident at 58, Windsor Street he would for 23 years until his retirement, in 1962, be employed in No. 3 signal box although, due to failing health, for the last few months he reverted to train reporting. After World War One, with cars becoming more numerous Mr. Cecil Hands shrewdly converted his stables into a garage and he also offered a taxi service, which in later years would even make the acquaintance of royalty. For the railway, however, the station was already acquainted with royalty for just after the war the Prince of Wales could often be seen at Bletchley, arriving by a Royal coach attached to the rear of an express. The reason for his visits was to attend the Whaddon Chase Hunt - his horses being schooled and cared for at stables situated in Great Horwood - but not everyone was initially impressed by these regal visits, especially Bill Tarbox, the Horse Shunt Driver, whose horticultural abilities had brought Bletchley station the award of 1st prize in the Station Garden Competition. On one occasion, having detached the Royal Coach in preparation for the return journey, Bill was not amused to see a well dressed man picking one of his prize roses. In fact, rampant with rage, he made his feelings vociferously known, whereupon the man duly apologised, explaining that he had picked the specimen especially for the Prince of Wales. The amused Prince then offered to pacify the situation by sending Bill plenty of rose cuttings! Apart from such patronage Bill’s gardening expertise was then again recognised in 1927, when he was presented with a medal, and illuminated address, for having brought the station gardens ‘into the state of cultivation which is so well known to the many travelers of the L.M.S. Railway’. A native of Steeple Claydon, Bill had come to Bletchley at the age of five and began work on the railway in 1892. Also being a bandsman in the Salvation Army, at the age of 66 he died at 12, Railway Terrace in 1942. During World War One, the Government had assumed control of the railways and in view of the wartime experience, in 1923 for a more efficient and economical operation they amalgamated 120 railways into four groups, the London Midland and Scottish, Great Western, London and North Eastern, and Southern. Thus into this new arrangement now came John Wickes, a native of Rugby, who having begun his railway career as an office boy, would now be District Controller at Bletchley. (He retired from the railway in 1930). From a position as a porter at Euston station, in 1921 Percy Prior arrived at Bletchley as a goods guard, an employment he would then continue until his retirement from the railway in 1956. Born at Cranfield, as an Old Contemptible and holder of the Mons Star he had served during World War One as a Sergeant in the Royal Artillery, and during World War Two would serve in the Home Guard. After the war, from 1945 until 1963 he then regularly marshalled the annual British Legion Remembrance Day parades in the town. Sadly on March 2nd, 1924 Joseph Dibbs, for many years the Chief of the Locomotive Department at Bletchley, died at the age of 87 but he would at least be spared any involvement in the legal unpleasantness the following year, when Sir Herbert Leon, of nearby Bletchley Park, who had frequently loaned his grounds to the railwaymen for their charitable Hospital fund and Orphan Fund events, (and in recognition of this had been made an Honorary member of the Trade Union), took out an injunction against the L.M.S. Railway, claiming that excessive smoke from the Locomotive Shed was causing damage to the trees in Bletchley Park. With the court deciding against the Company, as part of the remedial measures the breakdown train would now be stabled elsewhere, and the chimneys on the Locomotive Shed heightened. In addition, Welsh coal was to be used for lighting up the engines, with Inspectors detailed to watch for any ‘black smoke’ offenders.