![]()

The contents on this page remain on our website for informational purposes only.

Content on this page will not be reviewed or updated.

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

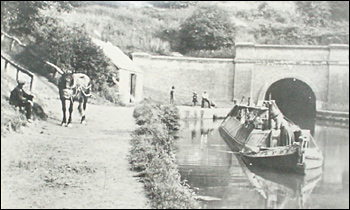

Digging Blisworth Tunnel

|

||

|

||

|

When the Grand Junction Canal Act was set out, in 1793, it was decreed that ‘adjoining to the said Village of Stoke Bruern,’ nothing in the wording should allow the proprietors ‘to cause any of the aforesaid Earths, Stone, Gravel, or other Materials, which may be dug to make the said Canal, to be carried or laid on any of the Homesteads and small Mowing Grounds.’ However, for the canal diggers their immediate concern was the geological strata, and by 1796 the Canal Company was having to deal not only with despondent contractors, but also the possibility of the excavations being flooded by hill water. In fact following consultations it was wisely decided to re-route the proposed Blisworth tunnel to a point just east of the original line at the northern end, and so cause the termination at the south to be some 130 yards west of the projected intention. Yet to carry off the hill water it would be necessary to dig a small pilot tunnel, beneath the proposed main excavation, and because of this delay the Canal Company decided that other projects elsewhere needed priority. Therefore only six men were left to continue the tunnel excavations, and as an interim measure a road would be laid over the course of the route. However, this soon proved unsuitable for heavy loads, and in March 1799 it was proposed to use a cast iron railway instead. Then with the Blisworth Tunnel as the only unfinished stretch of the canal, plans were introduced to hasten it’s completion, and for the excavation 19 shafts were sunk to the required depth, after which the digging commenced in either direction. Horse drawn cranes winched out the spoil in baskets, and the mounds formed by this dumping may still be seen. After the completion of their section all the shafts were back filled except four, which - with brick chimneys erected on the surface, to prevent objects from falling or being thrown down the opening - were left to provide ventilation. As for the tunnel being haunted, this seems of little surprise, for two men crashed to their doom in October 1803, when a shaft bucket slipped off the hook of the crane. As for another tragedy, a story is told from the later stages of the work, when the navvies were allowed only 20 minutes for lunch. Supposedly, when his wife arrived late with his dinner one Irishman, possessed of a rather hot temper, became so enraged that he grabbed his pickaxe and took off her head in one swipe. However, so as not to cause any delay the incident was hushed up, and, with the body being buried somewhere in the tunnel, the woman’s spirit is still said to haunt the watery confines. Eventually, with all the constructional difficulties overcome the tunnel was formally opened on Monday, March 25th 1805, and the first boat, carrying an assortment of local worthies, completed the 3,075 yard length in an hour and two minutes. Now the way was clear for commercial traffic, and to great excitement in May 1806 the first such vessel - laden with 100 sheep for the London market - set off from Northamptonshire, completing the 95 mile journey in 53 hours. But soon the railways, and later the roads, would siphon off the commercial trade, although the present popularity of leisure boating has ensured that the canal still remains in regular use today.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||