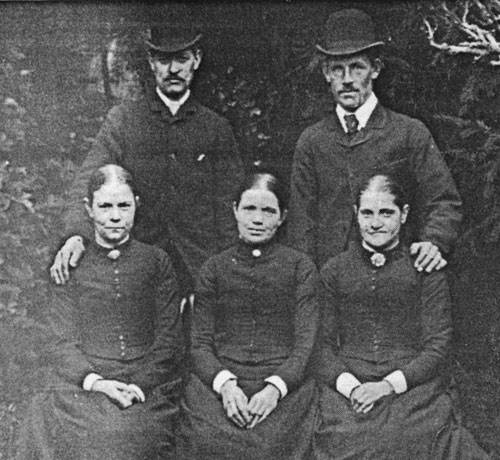

Seventy years ago, the small north Bucks village of Stoke Goldington straddled what was then a peaceful country road, but which with the advent of the combustion engine soon sprung to life and now forms part of the A50 between Northampton and Newport Pagnell. In this village was the cottage home of the Godfreys, a typical lace making family, in which lived my great-aunts, the Godfrey sisters. The illustrations to this article are from photographs taken of the family by my father during the first decade of this century.

The three Godfrey sisters lived together in a double-fronted cottage with its front doorstep butting on to the cobblestone footpath. Its geranium-filled windows gave an unobstructed view of the Congregational Chapel and Chapel House (now "The Manse" occupied by Sir Robert Bradlaw) just across the street, with the date 1819 stilt .plainly visible. Judging by the layout of the cottage interior, with its wider-than-usual staircase hung with the familiar brass bed warming pans, it had in its original form obviously consisted of two separate dwellings.

The solid floors at ground level were constructed of red bricks laid edgeways - hard wearing and somewhat uneven, but always kept remarkably clean. Similar red bricks, most probably made and baked in the local brickyard, paved the floor of the open passage which ran parallel to the rear wall of the cottage, and gave access to the only fresh water supply available, an external cold water tap; though this was ultimately piped into the pantry-cum-wash-house. Nearby stood a huge butt fed by a pipe from the roof to provide a constant reservoir of soft rain water. A four-foot brick wall buttressed the higher level flower, fruit and vegetable garden, with its uneven paths leading to the poultry run and the dry closet; the whole area being enclosed by a six-foot high brick wall.

The back parlour window with its wide, low window seat looked out on this garden, but the most interesting portion of this parlour was its ancient fireplace and chimneypiece. Most likely dating back to the early 1800s, it was typical of the almost primitive facilities provided in most of the cottages built at that time. Surprisingly, there appeared to be no obvious difficulty in meeting the basic household cooking requirements, though the absence of an oven meant that cakes, Sunday joints, had to be taken to the communal bake house higher up the street. The parade of villagers, each carrying the weekend joint in a baking tin containing the Yorkshire pudding batter, to and from this bake house was a picturesque Sunday ritual which afforded ample opportunity for relatives and friends to meet and tarry awhile exchanging family news and gossip. (If you have never tasted Yorkshire pudding baked in this fashion, richly flavoured with the natural meat juices, try it, you are in for a real treat!)

The three Godfrey sisters, spinster members of a family of seven were my great-aunts Sarah, Mary (better known locally as Polly), and Esther. At intervals they were joined by their elder sister, Elizabeth (widow of Richard Green), my grandmother, who as midwife and nurse was frequently engaged for quite lengthy periods by families living in the vicinity or surrounding villages. My mother (Annie) spent her childhood in Stoke Goldington, but in her teens ventured out into the Big City, obtaining a post at the Great Northern Hospital, London. My father (George Arthur) lived nearby. They met at the Upper Holloway Baptist Chapel, were married there in 1895, moved to Yorkshire in 1901 and settled in Harrogate after living a few years in Leeds and Ripon.

Opportunities for education were not established in Stoke Goldington until 1837. The first schoolroom - which the rector of that day described as "imposing, and an ornament to the village" - was opened in 1839, admission fees being 2d. per week for the first child and one penny for each additional child of the same family. The children's pence, if amounting to less than IOs. per week, were supplemented by the committee and constituted the teacher's salary. At its peak there were seventy to eighty children attending, and the salary rose to 15s.

Many village children, even from the tender age of six years, were employed at home lacemaking or attending one of the ten lacemaking schools. Consequently, with such a limited scope, it will be appreciated that my great-aunts, in common with most of the village girls, had little choice but to take up lacemaking at a very early age and, inevitably, their education suffered. Esther, being the youngest, had the greater opportunity and thus became the "brains" of the Godfrey trio, and under her capable hands and careful guidance the domestic wheels certainly appeared to run very smoothly.

Having devoted most of their spare time - but never on Sunday - to the tossing of bobbins and the transplanting of numerous pins, it will be seen that the monetary returns could hardly be regarded as fair compensation for the untiring effort incurred. There is little doubt that the combined earnings of the Godfrey sisters from lacemaking would barely have been adequate for their needs had they not been able, cheerfully and in good heart, to supplement their standard of living by utilising to the utmost the many natural resources available to them. They were not alone in this, of course, for these small rural communities seemed remarkably adept when it came to extracting the very last ounce from nature's bountiful Store. Every available piece of ground was carefully cultivated, and poultry and bees accommodated if at all possible.

Fields and hedgerows, in season, yielded mushrooms, berries of every description, nuts, hops and herbs; all gathered and 1preserved in true squirrel fashion. Regular collectin4 of wood for fuel was a must. The harvesters of those days were by no means one hundred per cent efficient and this gave the gleaners a welcome opportunity to collect a useful free bonus of grain to build up winter stocks of food for poultry. The beekeepers made a practice of extracting (through a muslin bag) the liquid honey from the combs, after which the remaining wax was melted down into convenient blocks which, in addition to any surplus honey, were readily sold.

In spite of their diligence and industry, these fine characters who had been making lace since their childhood were unfortunately fighting a losing battle, for even as early as 1819 a certain John Heathcoat found it practicable to produce lace by machinery, and within a few years the demand for the handmade variety began to fall. However, it took the best part of a century before the pillows, bobbins and "horses" were finally laid aside, and the soft music of the bouncing, beaded bobbins, which at one time could be heard when passing by the open doors or windows of most cottages, slowly died away, leaving the making of this fine lace to develop into a leisurely form of handcraft to be indulged in by a small group of enthusiasts. In this respect it is pleasing to note that during recent years there has been a steady revival of interest.

In conclusion it must be said that I personally regard it as a privilege to have had the great pleasure, during my impressionable years, of enjoying twelve months' holiday - virtually a "Year of Augusts" spread over twelve years - in the delightful company and environment of these wonderful characters, and meeting so many of their contemporaries. The passage of time has seen their cottage and adjacent site replaced by a group of modern dwellings. Nevertheless, memories linger and I shall never forget the peaceful contentment of these villagers, for they have left a lasting impression so strong that in retrospect, one is left wondering whether the so-called advantages of modern education and science have really brought about a betterment in human behaviour and relationships.