|

|

2(Reproduced by kind permission of the author) |

| HARRY ARMSTRONG can rightly be called one of the last great lace men setting up the Bucks. Cottage

Workers’ Agency in 1906 because he felt there was a need for someone to collect and market the lace made by the village women. He maintained that previously there had not been a definite, regular market for their work and many had given up lace making. Harry saw that the local lace-making industry needed an assured market for sales to encourage women to take up their pillows again in order to delight the ladies who could afford to adorn their clothes with such delicate lace, and also use it to decorate the contents of their linen cupboards. He saw himself as the man with the necessary drive and energy to do so. He was the perfect example of a successful advertising campaigner and public relations manager. ************************************************************************************************************************************************************************* Henry Hilliard Armstrong was one of the eight surviving children of his father Charles’s first marriage. His father had been born at Holborn, Middlesex and was married in London, although his wife, Anne Frances, had been born at Applesham in Hampshire.

After the marriage, Charles and Anne moved to Stoke Goldington in North Buckinghamshire and ran a grocery business from 20 High Street. (left) This business later expanded to include drapery and involved a delivery round covering Hartwell, Hanslope, Haversham, Wolverton, Bradwell through North Crawley to Cranfield and through Lavendon to Stevington.

Charles’s wife died in 1894 at the age of 38. He then married a local girl Amy Adams, and had four more children; two of whom, Arthur and Alfred Donald, are better remembered by Stoke residents as ‘Fleece’ and Don. (‘Fleece’ was so nicknamed because of his childhood mop of tight white curls.) Arthur and Don later took over their father’s extensive drapery round. Possibly through his step mother’s lace making expertise as a Point worker, Harry became interested in, and concentrated on, developing the lace marketing side of the business, founding in 1906 the “Bucks Cottage Workers Agency” from an outbuilding in their back garden. The Agency was self-supporting, thereby relieving the workers of any injured self-respect or encroachment upon their independence.

An early advertisement of June 1909 in the ‘Needlecraft Monthly Magazine’ exhorted ladies to:

In another undated advertising sheet he claimed that, by encouraging the hand made lace industry, the customer would be helping to rid society of unemployment as well as conserving the gifts of nature…

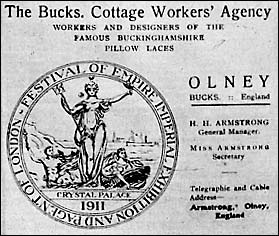

The business prospered and in 1909 moved to Olney, three miles away, to be near it’s Railway Station with the obvious nationwide rail and postal links. The lace makers continued to work in their own homes and the premises in Midland Road were used as offices, warehousing etc. and a separate building to the rear was used as a sewing room where exquisite sets of lace trimmed trousseau underwear were made. The lace was always whipped with rolled hems onto the handkerchiefs and other items produced. He imported handmade Cluny lace from Belgium and it is possible that the Irish crochet and Devonshire (Honiton) lace he sold was also bought in from those areas. Two years after the move to Olney, in 1911, he was awarded a Gold Medal at the Festival of Empire and Imperial Exhibition held at Crystal Palace. The award was for the Buckinghamshire hand made lace of his workers for the general excellence of workmanship. He was obviously very proud of this award and used it extensively in his advertising. In a pre first World War advertisement he stated that he had agencies in Australia, South Africa (through his brother, Em, who married a French girl, Marie,) and Canada (through his sister, Hilda, who went to Buffalo). He also had agents canvassing for him in London and Birmingham. A 1916 advertisement in ‘Fancy Needlework Illustrated’ stated that the Agency gave regular employment to upward of 600 cottage lace makers who worked in their own homes, and it went on to exhort – “It is the duty of every English lady to encourage a Home Industry”; this advertisement was in the name of Mrs. (Nellie) Armstrong and the previous one was signed Mrs. H Y. Armstrong. Harry always traded as Mrs. Armstrong; obviously thinking his customers would be more sympathetic in their dealings with a woman. An undated handwritten letter, possibly written in the 1920’s, shows how Harry traded on women’s sympathies:

Harry published a 144-page catalogue sometime between 1911 and 1919 (possibly pre-First World War, judging by the fashions) with historical articles as well as priced illustrations of all the yard lace and lace trimmed articles available. At the end of the catalogue he states that Miss Hilda Armstrong (his sister) was prepared to give personal lessons in lace making, anywhere in the United Kingdom for 2/6 an hour plus travelling expenses. She was also willing to visit the Continent if sufficient pupils were available. Now this is surprising, as the family says not one of Harry’s sisters learned to make lace! Perhaps he would have arranged to send someone in her place had he been taken up on the offer!

Trade stand in Buffalo, Canada

In 1919 Harry Armstrong published ‘The Romance of the Lace Pillow’ which was written by Thomas Wright, the local historian. In the book, Thomas Wright, who regarded Harry Armstrong as an authority on the subject of Point d’Angleterre, stated that Harry had invented a collapsible pillow stand and that the Bucks. Cottage Workers’ Agency never used cotton thread, as it had no durability any new thread offered to them was always put to the test of soap and water. On page 239 in his book, Thomas Wright describes the establishment of the Bucks. Cottage Workers’ Agency thus:

removed to Olney, being impelled thereto not only on account of postal and railway advantages, but also because of the town’s association with the poet Cowper, whose name is so intimately associated with the lace industry. A large building was purchased, and experience soon proved the wisdom of the choice. The industry being carried on under more favourable conditions went forward by leaps and bounds, orders arriving by every mail, not only from homes in the British Isles, but from all parts of the civilised world. In 1911 the Agency was awarded a gold medal at the Festival of Empire and Imperial Exhibition held in that year at the Crystal Palace. As the above extract suggests, Harry was an exacting employer, demanding the best of everybody, from the lace makers to the office staff. Although he never married, living with his sister Hilda at 29 High Street South (now Cole’s bakery) before her marriage to Jack Longland, he always had an eye for the ladies. There are tales of him inviting his female employees for rides up the river in his punt. Despite the problems of the Depression in the 1920’s, the business continued to expand (helped through his sister Hilda’s sojourn to India after her marriage) and by the late twenties Harry was looking for bigger premises. A vacant site in Olney’s High Street, caused by a fire, attracted his attention and he set about dreaming of erecting an elaborate building, the like of which Olney had never seen. He employed George Knight, my father-in-law, to build it and George had to dissuade Harry from some very fanciful designs, including Corinthian Columns! The resulting edifice, built in 1928, is quite pleasing with it’s stone lettering and carving of a lace maker, said to be the work of the sculptor of Northampton’s War Memorial. There were originally three other carvings over the doorway; of a bobbin winder, light stool and bobbin stand. These were not allowed to remain unsupported over the door for long as they were too large and heavy, being bigger than gravestones. They were rediscovered a few years ago in a garden of a house in Weston Road. This house had once belonged to a lady friend of Harry Armstrong. They are now on permanent display at the Cowper and Newton Museum, Olney. Harry moved into the flat above his Lace Factory and kept a strict check on his workers. He was a real terror to work for. George Knight was in the office of the Lace Factory one day when two women came in, one after the other, with their lace. The first woman was well to do and Harry praised her and made a great deal of fuss of her, then, when she had gone, threw her lace on the fire. The second, poorer woman, came in and Harry treated her quite differently. He criticised her work, saying she must do better, and carried on so alarmingly at her that the poor woman left in tears. When she had gone George asked Harry why he had treated her so harshly. “Oh, well”, Harry said, “she is one of my best workers, and I must keep her work up to scratch”. Harry published ‘A Sixteenth Century Industry’ sometime after 1936. In this book he gives a history of the lacemaking industry, extracts from various articles about lacemaking – one being delightfully entitled ‘A Woof for Women’ and describes the work of the Cottage Workers’ Agency – and also illustrates and advertises the laces which could be purchased from the Agency. He proudly lists the awards won by the Agency, including a Gold Medal from the Paris Exhibition of 1925, and includes his usual plea to help the ‘lace makers in distress‘ by purchasing their merchandise. The book was obviously used for advertising purposes but it is not known whether it was sold or given away gratis with orders. Possibly customers ordering goods over a certain value were sent a copy. Harry Armstrong travelled extensively and while in Scotland in 1943 was taken ill and died on 16th July. He was aged 57. His demise was possibly caused by a ruptured spleen although it is known that he suffered from a blood disease. He was buried 5 days later in Stoke Goldington Churchyard. After his death the Museum at Olney was given a large wall case of Antique Bobbins which he had collected, and a model of a lacemaker’s lights. There are local tales of sacks full of bobbins being burnt when the lace factory was cleared. It was used by Polaroid during the remaining years of the Second World War and was then taken over as a lampshade factory in the 1950’s, before being converted into flats and apartments in 1988. The last sad tale of Harry Armstrong’s Lace Factory is told in a letter sent to the Cowper Museum in November 1987 by Mr. Francis Giles. Mr. Giles, a carpenter from Aspley Guise, worked during 1947-1949 for the building firm of Garner and Sons in Denmark Street, Fenny Stratford, Bucks. He wrote:

Mr. Giles sent the medallion, he rescued from the fire, to the Museum. It is golden in colour, two inches in diameter and is inscribed. It has a raised crown and wreath design exactly as depicted in Harry’s first catalogue but the wording is slightly different. The illustration in his catalogue has the medal awarded to “The Bucks. Cottage Workers’ Agency, Olney Bucks.” But then he could hardly run his business under the name of Mrs. H. Armstrong and have the medal awarded to Henry H. Armstrong!

Could this be Harry’s much-prized award of 1911?

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to record my special thanks to David Armstrong and his mother for their helpful co-operation in the compilation of this booklet. Without their assistance there would have been no family background or photographs. I am also grateful to The Stoke Goldington Association for inviting me to speak on Harry Armstrong thus initiating this research. The notes for the talk have been expanded into a booklet which is sold for the benefit of The Cowper and Newton at Olney, where a large lace collection is housed. There are very few known photographs of Harry Armstrong; perhaps he disliked being photographed, as he did not wish to dispel the illusion of “Mrs” Armstrong. Elizabeth Knight (September 1989) |