This article is based on an interview with Brian (better known as Charlie) Mynard and provides an insight into the activities and pastimes of a local lad during World War II. Brian was born in 1930 into a farming family and was nine when the war started on 3rd September 1939. Brian died in January 2015.

The video clip is of Brian recounting his involvement in the impromptu VE-Day bonfire party on the Knoll, Olney in front of the Castle Inn.

Schooling during wartime

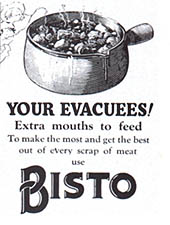

The War affected us children quite considerably. Evacuees came down from London by the coach-load at the end of August and the beginning of September 1939 so for a start, schooling was affected. There was so many evacuees that they and the local children couldn’t all fit into the classrooms. Some rooms were physically divided into two but that wasn’t very successful. Eventually the local children went to school in the mornings and the evacuees in the afternoons. As locals, we thought it was wonderful having every afternoon off; better than the evacuees who had the morning off and then had to go home and get cleaned up ready to go to school for the afternoon.

The War affected us children quite considerably. Evacuees came down from London by the coach-load at the end of August and the beginning of September 1939 so for a start, schooling was affected. There was so many evacuees that they and the local children couldn’t all fit into the classrooms. Some rooms were physically divided into two but that wasn’t very successful. Eventually the local children went to school in the mornings and the evacuees in the afternoons. As locals, we thought it was wonderful having every afternoon off; better than the evacuees who had the morning off and then had to go home and get cleaned up ready to go to school for the afternoon.

Until we were eleven we went to Olney First School, which is now the Olney Centre. We didn’t talk much about the war. In the playground we were too busy playing ‘tag’ or something similar. Every day we had milk, mostly in small, one third of a pint, bottles. As far as I can remember we were never short of pencils and there was always plenty of ink. We wrote with those old fashioned nibs which once they started to cross, were useless.

At the age of eleven we transferred to Olney Secondary School at the top of Moore’s Hill, now Olney Middle School. Here there were just three classes, for the eleven to twelve, twelve to thirteen and thirteen to fourteen year old children. We had a huge school field to play in, available for whatever the teachers felt was needed, and tennis courts were situated at the rear of the headmaster’s house. My headmaster was Mr L Lisle Orchard. We had art and science rooms and also cookery rooms for the girls. There were no cooking facilities for girls at the Newport Pagnell School so the girls used to come to Olney for their cookery classes. The older lads at Olney used to look forward to that, it was the bright spot of the week! When I was fourteen in March 1944 I left school.

Many of the early evacuees stayed only until the bombing paused in London and then they returned home. I should think it would have been 1942/43 when we children went back to school full-time. However, other families whose houses had been bombed then came to Olney. It seemed to us that a younger generation was being replaced by an older generation.

Many of the early evacuees stayed only until the bombing paused in London and then they returned home. I should think it would have been 1942/43 when we children went back to school full-time. However, other families whose houses had been bombed then came to Olney. It seemed to us that a younger generation was being replaced by an older generation.

My wife Floss first came to Olney as an evacuee in 1939 aged eight. Her family, named Callow, were later bombed out and came to Olney from London in 1942 after the youngest child, Joan, was born. A little cottage became vacant in East Street and the family took it. Floss was one of eight children; there were two boys and six girls, with an age gap of about three years between each of them. The oldest boy, Joe, was in the Army and took part in the D-Day landings. The oldest girl, Ivy, was in the Land Army. Alice, the second daughter, contracted consumption and died. Lesley, the second son, came to Olney with Floss and her younger sister, Frances. Sylvia and Joan, the youngest daughters, came to Olney with their mother in 1942. Their father, Joe, joined them later at the end of his wartime service in Portsmouth. Since our marriage Floss and I have lived in the house in Cowper Street which I moved into with my family in 1934, over seventy years ago.

Youngster’s Pastimes

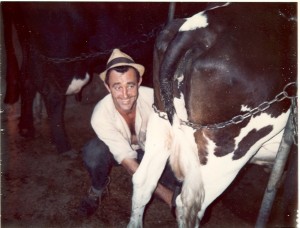

During the daytime I avoided listening to the radio if I possibly could because it was all doom and gloom. In fact, I was rarely at home. If I could get out of the house, I did, because every time I stopped to turn around, my parents found me work to do, and you soon get wise to that! Being part of a farming family, it was ‘You’ll come with me today, my boy’, even if there was a game of football in the offing. No one said ‘Will you come with me?’ it was ‘I don’t care what you’re doing, you’re coming with me’. This way of thinking was the norm in those days and of course it was expected that it would all be done for nothing, just for love. When I was at my grandfather’s farm we worked all the daylight hours. The cows were milked by hand 365 days a year, including Christmas Day.

As youngsters, I don’t remember playing games related to the war. I never had any toy guns or that sort of thing. If anyone had one it would have been made by hand from a piece of wood, as there was nothing else. We used to play hopscotch in Midland Road, the pavement slabs were ideal because they had the off-set squares. We had hoops made from a band of steel; the blacksmith used to make them by bending the steel to form a ring.

As youngsters, I don’t remember playing games related to the war. I never had any toy guns or that sort of thing. If anyone had one it would have been made by hand from a piece of wood, as there was nothing else. We used to play hopscotch in Midland Road, the pavement slabs were ideal because they had the off-set squares. We had hoops made from a band of steel; the blacksmith used to make them by bending the steel to form a ring.

We also had whips and tops in those days; usually a round wooden top about two inches across with a metal stud at the bottom. If the stud was lost, the top didn’t work. Luckily, at the beginning of the war there was a man named Woods who had moved out of Brocks Garage into a workshop at the bottom of the lane joining Wellingborough Road with Cowper Street. He used to replace the studs in our tops for free. He repaired cars and motor bikes. He had a petrol pump alongside the workshop; the remains of the pump are still there, but it’s now well past repair. He was a lovely old boy; when we spoke to him he always replied with “Yes my king” or “No, my king”. There was no “Yes Sir” or “No Sir” in conversations with him!

In the 1930s a very smooth experimental surface had been laid down along the whole length of the High Street. This surface was brilliant for us roller skating youngsters. Local boys and girls, including Daphne Bird, Violet Wood, Denis Tomlin, Tom Edwards, Maurice Crouch, Don Andrews, Phil Wickens and Keith Johnson all had roller skates. Then, particularly since it was wartime, there were no cars to worry about. The only traffic was an occasional horse and cart.

As a farm worker my father was in a reserved occupation. He used to go round with a horse and trolley on Saturday mornings, collecting waste paper. The kids would run after him for comics, and of course, if he had any to give them, they read them and then recycled them.

I belonged to the Scouts and together with the others in the troop, we were required to act as runners for the National Fire Service. We took turns one night a fortnight to be on duty with the Firemen. In the absence of telephones, our job was to run messages anywhere in the town. So the boys were quite involved in supporting the war effort at that stage, but the girls weren’t involved quite so much because they were more shielded in those days.

Early days of the war

Every house had to put up blackout curtains. Not even a chink of light was allowed, and if one was seen, you were pulled up, but I can’t remember anybody being fined for showing a light. No material was issued for the curtains so they were made from anything that came to hand. As long as the blackout curtains didn’t show light through them you could put up what you liked. There were no tarpaulins or black plastic! Bicycle lights or car headlights had to have black shields with attached flaps, so that light just shone on the ground in front of them.

We were all issued with gas masks and we took them to school for the first two or three years. If you arrived at school without your gas mask, you had to go home and fetch it and you were also given a black mark!

We were all issued with gas masks and we took them to school for the first two or three years. If you arrived at school without your gas mask, you had to go home and fetch it and you were also given a black mark!

Lodge Plugs moved into the factory building at the top of Midland Road very early in the war, probably at the beginning of 1940. The factory made sparking plugs for aircraft engines and was a subsidiary of Lodge Plugs in Rugby. The workforce was expected to work shifts. The shift started at 7.00 in the morning and the workers would go home for half an hour at midday; they would go home again for half an hour around 5 o’clock and then return until 7.30 or 8.00 pm at night. There must have been more than 100 women working there, but only about half a dozen men. To get there they used to bike from Brafield, Newport Pagnell and other areas in the district.

The first air-raid warning in Olney was from the steam driven tannery ‘buzzer’. The tannery boiler was never allowed to go out. At that time it was coal-fired and didn’t switch to oil until well after the war ended. Later a siren was positioned on the end of the Fire Station at the back of the Two Brewers inn. The two poles and the bracket on which the siren was mounted remain there to this day. I can’t ever remember hearing the air raid siren when I was at school. It used to go off in the evenings and you would then sit under the table or under the stairs, but nothing spectacular happened.

I think we had two bombs here in Olney. They were dropped in a field on the Clifton side of the river, opposite the bathing place and not too far from the railway line. The blast travelled across East Street, funnelled up the back of the Two Brewers yard and through an archway into the High Street. It blew out the two windows across the street in Albert Lineham’s shop (which was called ‘the Linco’). The shop windows were boarded up for years because glass was unobtainable during the war. The Linco is now Stephen Oakley’s Estate Agents. In bygone days, the archway (where the bar of the Two Brewers is today), was used by Olney’s horse-drawn fire engine to enter the High Street.

Locals who owned shotguns were each issued with a box of cartridges filled with balled ammunition instead of lead shot. Quite a few people in a community like Olney would qualify because many followed countryside pursuits. A shotgun licence cost ten shillings a year. The issue of balled ammunition would have happened in the early 1940’s. I remember Dad having his box of cartridges because, like many others, I replaced the lead ball with lead shot and filled them up and used them!

In those days if you owned a gun and had cartridges, you used it. All boys working on the farm could use a gun, but cartridges for shooting game were unobtainable and many people filled their own. Carl Clifton used to make lead shot in Olney which he put in little bags. The lead shot was made by dropping melted lead through a coarse sieve from a height; the higher the drop, the smaller the shot. Carl’s nickname was Paffan, probably an abbreviation of ‘Paraffin Man’. He worked all his life at Sowmans on the Market Place, and distributed paraffin around the town and villages; some of the younger ones were scared of him. He was a bit wild, he used to put ‘crow-scarers’ under dustbin lids which would make them rise higher than a house. Crow-scarers were sold in Sowmans and were essentially a set of crude ‘banger’ fireworks attached to a rope, for use on farms. The rope burnt very slowly and the fireworks went off every half an hour or so. One rope would last a whole day. If the crow-scarers were separated from the rope and lit individually, you didn’t hold onto them for too long, because once lit, they were on a very short fuse, lasting only one to two seconds.

There were ammunition dumps alongside the roads leading into Olney and even up some farm tracks. There were several hundred in this area, situated up Weston Road, Lavendon Road, Warrington Road and up the Hyde Lane right up to the farm. Farm road had them placed on both sides. The dumps were constructed from three half-moon shaped corrugated sheets of metal bolted together to form an arch. Several arches were bolted together to form the length of the dump; they were at least seven feet high in the centre. They were painted black and had camouflaged wire netting hanging across both ends.

The ammunition in the dumps included land-mines. These mines didn’t have fuses in them, so we lads used take their middles out and put them back together again so nobody knew we’d been. The mines were cylindrical; with a gap all the way round within the outer casing. The gap was filled with steel balls. You just took the cap off the end, tipped the mine upside down and a couple of hundred steel balls fell out. The steel balls were beautiful for using in a catapult, perfectly round, accurate, you could hit many a rabbit, or pheasant sitting in a tree. Of course, we all had catapults when we were young!

The ammunition in the dumps included land-mines. These mines didn’t have fuses in them, so we lads used take their middles out and put them back together again so nobody knew we’d been. The mines were cylindrical; with a gap all the way round within the outer casing. The gap was filled with steel balls. You just took the cap off the end, tipped the mine upside down and a couple of hundred steel balls fell out. The steel balls were beautiful for using in a catapult, perfectly round, accurate, you could hit many a rabbit, or pheasant sitting in a tree. Of course, we all had catapults when we were young!

Lorries, some belonging to the London Brick Company, went up and down Hyde Lane to the dumps all during the War and ruined the lane. Bill Campion was one of the LBC drivers. At the end of the War, Graham Needham took over the farm from a Major Randall. Graham applied to the government for a grant to lay a concrete lane. The application was successful and the concrete lane was laid by three Irish chaps, Paddy and Batty McGowen and Larry. The concrete started at Warrington Road and finished at the first cattle grid way up the lane. All the digging and shovelling was done by hand; the concrete was prepared using a small cement mixer. Maybe that’s how several farmers have concrete roads leading into their farms.

Army units were stationed in two large Nissen huts sited on the left hand side of Midland Road, opposite the entrance to Newton Street. The army also occupied factory and temporary buildings on the other side of Midland Road. In the 1950’s these temporary buildings were used by the Olney Boys Club and the Olney Youth Club, and have only recently been demolished.

I wasn’t really old enough to remember the call-up of Olney men into the Services. One neighbour that I remember well was Cliff Campion, Norman’s brother, who started in the Merchant Navy at the beginning of the War when he was 17. He later transferred to the Royal Navy. Another neighbour, Bill Howson, went with the British Expeditionary Force into France and was taken prisoner of war, as was Fred Halton, a nearby neighbour. They both spent some time in a German prisoner of war camp.

Rationing

The rationing affected everybody really, but with the farm in the family, this was not a serious problem for us. Milk was always available. At home in the evening, we used to sit round the fire listening to the radio (no television in those days), with a screw-top jar filled with the cream off the top of the milk. We shook the jar, first with one arm, until that arm got tired, and then the other, till that got tired. Then the jar was passed to the next person and by the time it had gone around the four of us, the cream had turned to butter.

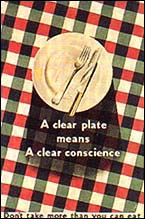

Again, the meat rationing didn’t really affect us. There were always rabbits, the odd pheasant and anything else that came along. You were allowed to kill a pig but I can’t remember whether it was once or twice a year. The smallest one of the litter was called the runt. If it was female, or a dilling, it could be kept for breeding, if it had 14 teats. If the runt was male or a barret, as they were called, then it would soon find itself in the stew pot.

Again, the meat rationing didn’t really affect us. There were always rabbits, the odd pheasant and anything else that came along. You were allowed to kill a pig but I can’t remember whether it was once or twice a year. The smallest one of the litter was called the runt. If it was female, or a dilling, it could be kept for breeding, if it had 14 teats. If the runt was male or a barret, as they were called, then it would soon find itself in the stew pot.

Living in a small country town, almost everyone had an allotment, so finding enough vegetables wasn’t a problem for most people. We were never short of potatoes or greens and we had all the seasonal vegetables. However, gardening was another chore that many lads had to do after school when their father came home from work. “Come with me my boy, up the garden”. “I don’t want to go up the garden; I want to go play football.” “You’re coming with me my boy”.

In the High Street, George Fowler’s fish and chip shop was open several days a week. The only nights the shop didn’t open were on Sunday and Monday, so although there were shortages, fish and chips were always available.

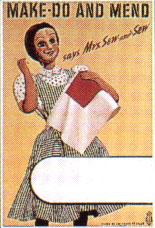

Clothes rationing was a different matter. School children over a certain height qualified for extra clothing coupons. I think the entitlement was an extra 20 coupons a year for those taller children. I qualified, and my sister Ruby immediately confiscated them. She was working at the Lodge Plug factory making sparking plugs for aeroplanes and earning money. Anyway, I hadn’t any money to buy clothes.

An ‘older’ Brian in the dairy

As farmers, we bought petrol from Brocks. It was rationed and we needed valid coupons. Souls also sold petrol and so did Sowmans on south side of the Market Place. Ordinary people had to have a good reason to buy petrol. For example, if someone in the family was disabled, then they would be allowed a little. Farmers could buy petrol because tractors started on petrol and then ran on TVO (tractor vapour oil). Every time the tractor’s engine stopped it had to be switched over to petrol because if the tap was switched to TVO the engine wouldn’t start. TVO was similar to paraffin, and could be used to clean anything. I think TVO was 11d (almost 5p) a gallon and I can remember buying petrol for half a crown (12 ½p) a gallon! I used to be given half a crown by my grandfather to buy petrol to start the tractor. He would say “Whatever have you done with it, boy, you only bought some a fortnight ago!”

Entertainment

The ‘Electric’ cinema in the High Street was open more or less all through the War, but by the time the films got to Olney some were up to 3 years old. Seats in the front row cost 4d. We could earn 4d by returning two 2lb jam jars to the International Stores or the Co-op in the High Street and collecting the deposit. I think the back row cost one shilling during the War. Later, around 1947 when I was courting Floss, it was 1/9d. A full house at the cinema was probably about 150 people. There were five seats on either side of the central aisle and at least 15 rows. The back five rows were raised, that’s probably why these seats were more expensive because you could see over the heads of the people in front. The cinema, or ‘the pictures’ as we called it, was quite an asset to the town.

During the war, I started going to ballroom dancing and old-time dancing with the Charlie West Band from Yardley Hastings. The Church Hall was the main social centre and Violet (Vi) Luttrell used to run 2/6d hops on a Saturday night. One week it would be ‘modern’ dancing and the next would be ‘old-time’. All the soldiers and young girls came to these hops which continued pretty well all through the War.The first floor room at the back of the Bull Hotel, the Masonic Room as it was then called, was also used for hops, but these were priced out of our pocket. The Masonic Room became more popular for social events after the War. The community spirit in Olney was very good. We didn’t have a lot but what we had we shared between neighbours. Front and back doors were never locked; sometimes the key would be left in the door. If a door opened it was often somebody putting something in, like a cabbage or a rabbit. No-one took anything because no-one had anything and so everyone was on a par. You didn’t crave after anything because it was unobtainable. Although no-one had a lot, you didn’t need a lot to be happy. It wasn’t like it is today!

During the war, I started going to ballroom dancing and old-time dancing with the Charlie West Band from Yardley Hastings. The Church Hall was the main social centre and Violet (Vi) Luttrell used to run 2/6d hops on a Saturday night. One week it would be ‘modern’ dancing and the next would be ‘old-time’. All the soldiers and young girls came to these hops which continued pretty well all through the War.The first floor room at the back of the Bull Hotel, the Masonic Room as it was then called, was also used for hops, but these were priced out of our pocket. The Masonic Room became more popular for social events after the War. The community spirit in Olney was very good. We didn’t have a lot but what we had we shared between neighbours. Front and back doors were never locked; sometimes the key would be left in the door. If a door opened it was often somebody putting something in, like a cabbage or a rabbit. No-one took anything because no-one had anything and so everyone was on a par. You didn’t crave after anything because it was unobtainable. Although no-one had a lot, you didn’t need a lot to be happy. It wasn’t like it is today!

D Day and VE Day

Early in 1944 there were army vehicles on manoeuvres everywhere. The vehicles ranged from Jeeps and Bren Gun Carriers, which were wheeled, to tanks, which were tracked. Little did we know at the time that it was in preparation for D-Day. I remember as lads we were all over these vehicles when they were parked all up East Street for the night. Apart from photographs in the newspapers, it was the only chance we had to get a good look at them. They were parked everywhere in the town. There were no private cars in the streets as they were all garaged.I did once see an American transporter vehicle going north carrying a huge tank. It couldn’t get under the railway bridge on the Wellingborough Road so eventually all the tyres were let down and the transporter just managed to manoeuvre underneath. The tyres were then re-inflated on the other side of the bridge. I think the bridge had a 14 feet 9 inches clearance, double-decker buses could get under it with ease. (See picture of the bridge)

At the end of the War in Europe on VE Day we needed to find a way of celebrating the occasion, alongwith the rest of the country. It was local knowledge amongst us lads (I was a 15 year old at the time), that there was an ammunition dump containing thunder-flashes near the Alcove at Weston Underwood. Thunder-flashes were used for army training purposes and were about the size of a half-litre beer can. We used to ignite them on a Swan Vestas match box. They had a barrel and a fuse about four inches long so they couldn’t be held too long before they exploded. All the lads, I think there would have been about 50 of us, fetched the thunder-flashes from Weston and before long half the town had them. Somebody came up to me and said, “I want some thunder-flashes”, and I said “I’ll sell you some for a tanner”. More of this later.

At the end of the War in Europe on VE Day we needed to find a way of celebrating the occasion, alongwith the rest of the country. It was local knowledge amongst us lads (I was a 15 year old at the time), that there was an ammunition dump containing thunder-flashes near the Alcove at Weston Underwood. Thunder-flashes were used for army training purposes and were about the size of a half-litre beer can. We used to ignite them on a Swan Vestas match box. They had a barrel and a fuse about four inches long so they couldn’t be held too long before they exploded. All the lads, I think there would have been about 50 of us, fetched the thunder-flashes from Weston and before long half the town had them. Somebody came up to me and said, “I want some thunder-flashes”, and I said “I’ll sell you some for a tanner”. More of this later.

Later on, we lit a huge bonfire, where the Knoll now is, and of course we set off the thunder-flashes. The local people knew what was going on and we really did have one hell of an evening. It was a big celebration. Outside the pubs, the local publicans filled galvanised baths with beer. These were same ones used for bathing and by the women for the washing. Everyone just went along and, provided you didn’t lose your pot, you could drink as much as you liked. It was a wonderful, wonderful evening, particularly because we’d never been allowed to have a bonfire at night during the war. (Brian’s account of this VE Day celebration is on the video clip above.)

The local police soon found out that thunder-flashes had disappeared from the ammunition dump and started their enquiries around the town. They questioned the lad who said that he had bought some from me, so of course I didn’t have a leg to stand on when the police came around to my house. Later we all, at least a dozen of us, had to appear at the Magistrates Court at Newport Pagnell. Stan Goss and Stanley Lord were on the Bench at the time. I was fined five shillings and had a verbal slap on the wrist and told not to be a naughty boy. I was put on probation and bound over for twelve months. I had to pay the fine myself, as my father wouldn’t pay it. For a Court Appearance, every child had to have a parent with them, so there were quite a lot of people queuing outside the Court on that day!

At the end of the war the number of pubs in Olney was down to ten. Starting at the north end of the town and walking south there were The Queen, The Castle, The Red Lion, the Working Men’s Club, The Two Brewers, The Cock and The Bull on the Market Place, The Sun on Weston Road, then The Swan and The Boot. I was weaned on beer in The Queen. Father used to take me in there on Saturday and Sunday mornings and buy me half a pint of beer. “Don’t tell your mother” he said. But Mother smelled the beer and said, “Where have you been?” I replied “You’ll have to blame our Dad”. “I’m not blaming your father, I’m blaming you” was her reply. The Queen was built by Hipwells Brewery to service the railway. Although it was called a hotel I don’t ever remember anyone stopping there, then.

At the end of the war the number of pubs in Olney was down to ten. Starting at the north end of the town and walking south there were The Queen, The Castle, The Red Lion, the Working Men’s Club, The Two Brewers, The Cock and The Bull on the Market Place, The Sun on Weston Road, then The Swan and The Boot. I was weaned on beer in The Queen. Father used to take me in there on Saturday and Sunday mornings and buy me half a pint of beer. “Don’t tell your mother” he said. But Mother smelled the beer and said, “Where have you been?” I replied “You’ll have to blame our Dad”. “I’m not blaming your father, I’m blaming you” was her reply. The Queen was built by Hipwells Brewery to service the railway. Although it was called a hotel I don’t ever remember anyone stopping there, then.

All in all, I have fond memories of my childhood. The times were hard, but none the less, we got by because people were more neighbourly then, and we did have some fun.

Brian (Charlie) Mynard (Interviewed: 3rd December 2003)

Acknowledgements to various web sites for the illustrations

.

Copyright © 2005 Olney & District Historical Society