Before Jean left school, she was interviewed by the Careers Officer. A vacancy for an office junior had become available at Sowman’s shop, the well known emporium in Olney; she applied for the position and was successful.

Jean in her early Sowman years

Jean started work a month before the end of the school year, going to Sowman’s after school Monday to Friday, and Saturday mornings from 9 o’clock until noon. This was in 1958 and she was fifteen years old. When she started full time the hours were long; work started at 8.30am in the morning and finished at 5.30pm in the afternoon. Wednesday afternoon was early closing in Olney so the shop was shut. However, she did have alternate Saturday afternoons off, but when she worked a full day on Saturday, she didn’t finish until 6 o’clock. An hour was allowed for lunch and Jean always managed to go home for her meal. Holidays followed the traditional pattern; two weeks off in the summer, together with the Bank Holidays, including Christmas Day and Boxing Day, of course. Good Friday and Easter Monday were negotiable days. Stanley Lord, the Managing Director of Sowman’s, Leslie Fairey of ‘Allen’s of Olney’ and Wilf Turner, another ironmongers, used to confer with each other to agree the days the shops closed; either Good Friday and Easter Monday as in Bedford or Easter Monday and the following Tuesday as in Northampton. However, they always opted for the Good Friday/Easter Monday closing.

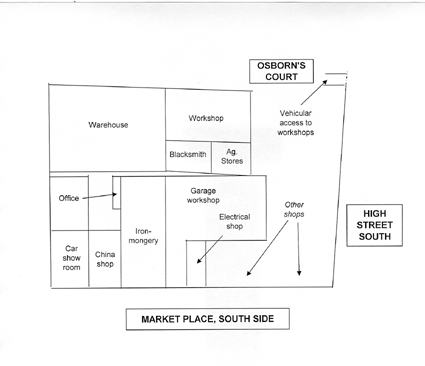

Sowman’s office accommodation was in a lean-to building at the back left-hand side of the main shop, opposite the lift and invisible from the front of shop. At the rear of the lean-to was the old warehouse where all the corrugated iron and rainwater goods were kept. To the side of the lean-to were out-buildings where a variety of sledge hammer and other handles were stored. (See floor plan below.)

Floor Plan of the Sowman Complex – Late 1950’s

The working conditions were quite Dickensian. Mr Andrews (who died quite young) was the office manager. His six office staff sat in a row on high wooden chairs at a high desk. Coffee and tea breaks were not allowed and so there were no tea-making facilities. When important visitors arrived, Jean had to go across the street and ask for tea from Mrs Loom’s tea shop, and when that wasn’t open, she had to go to the Olney Café (now Mario’s fish and chip shop). Otherwise, tea for personal consumption was brought in vacuum flasks. Empty cartridge boxes served as wastepaper bins. These were emptied every Monday morning and as Mr Andrews objected strongly to the smell of oranges they could not contain any orange peel or food! In any case, eating in the office was not really allowed. The office cleaning was done by the ‘junior’ who had to sweep, and every so often wash, the old ‘lino’ floor covering. The toilet was upstairs, had wood panelled walls and was ancient. There was an old sink and a built-in wooden cupboard. At least the lighting was not too bad as it was provided by fluorescent tubes. These were the conditions at Sowman’s in the late nineteen fifties, not that long ago! Nevertheless, chivalry dictated that when the girls had to take cash to the bank, they were escorted, usually by Tom Dix. He did odd jobs including cleaning the outside shop frontage, and occasionally driving the van.

As office junior Jean had to answer the telephones – ‘Olney 213’ and ‘Olney 217’. The equipment was housed in a wooden box in the corner on the wall next to Jean’s desk. The in-house telephone exchange was operated by a crank handle and calls could be put through to the garage, warehouse and shop floor. Hopefully, someone would answer the bell. Jean was also responsible for filing and general ‘dog’s body’ jobs. Filing consisted of two cabinets, with three drawers; one drawer for letters, one for invoices and another for receipts. Receipts were also kept on open shelves behind Jean’s desk prior to being filed.

By October 1958 Jean had progressed to ledger clerk, thereby missing the next stage up the office progression ‘ladder’ and leaving the more menial tasks to her juniors. This promotion was brought about by the marriage of Dorothy Peters (the previous ledger clerk) to Graham Wooding. This was a big step up for Jean; because she was good with figures she could be relied on to do the book-keeping accurately.

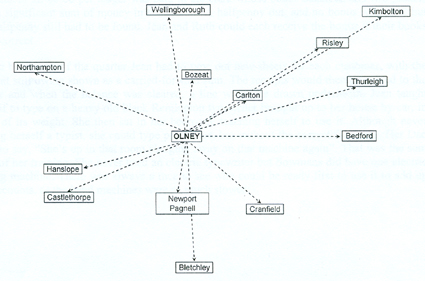

Sowman’s business covered a very large area. The sales ledgers were divided into East and West regions. The six ledgers for the East Region were looked after by Ruth Sharp (neé Perkins). These covered the area from Cold Brayfield to Kimbolton, including Cranfield, Thurleigh, Carlton and Riseley. Jean handled the six ledgers for the West Region. The first covered Weston, Ravenstone, Stoke Goldington, Tyringham, Gayhurst, Hanslope and Castlethorpe; the second covered Northampton and District; the third dealt with Bletchley and district; the fourth covered Yardley Hastings, Grendon, Easton Maudit, Bozeat; a fifth ledger addressed Emberton, Sherington and Newport Pagnell including Newport Pagnell Rural District Council. The Council lorries and vans used to come to Olney for petrol if they were in the area. The sixth ledger was a monthly ledger for Olney trades-people who were billed every month.

The general public were billed every quarter. The majority of customers had an account with the shop, so a record was kept of their addresses and purchases. When items were sold from the main shop, these were entered into a little duplicate book. The customer was given the top copy of the receipt and at the end of each day all the duplicate copies were collected up and sent to the office. In the late 1950’s, the items which had been purchased were entered into the duplicate book but not always priced up. Mr Charles Sharp (no relation to Ruth) used to come in from Sherington, to go through the duplicate book and enter the omissions. The entries were then transferred to the ledgers.

Watch a video clip of Jean describing Sowman’s Ledgers

The accounts were sent out each quarter on Lady Day, Midsummer, Michaelmas and Christmas. One of the tasks of the junior was to lick the stamps, a nasty tasting chore, stick them on the envelopes and then take them to the post office. Olney accounts were all delivered by hand; a pleasant duty when the weather was fine, but not so good on a wet day. When the ledgers were closed for each quarter, they had to balance to the nearest halfpenny. A bonus of £2-0s-0d per ledger was paid to the clerk whose books balanced and two pounds was a significant sum of money in the 1950’s. A halfpenny out, and no bonus was paid, but the halfpenny still had to be found. Jean and Ruth could each receive the bonus if their books were correct.

At the beginning of the quarter Jean had to type out new sheets for each customer, with the amount still owing shown as a carried-forward sum. The receipts would then be posted to the ledger and when the balance was cleared, a line would be drawn underneath. Jean taught herself to type on a heavy old black Remington typewriter brought up to her house by car, in view of its weight. She then sat in her bedroom, teaching herself to use it. Although never calling herself a typist, she could type pretty fast, but without the correct fingering. Her Dad used to say, “She’s up in that room clanging away on that machine again”. That was the sum total of her training. She never used an electric typewriter but Sowman’s did have one electric adding machine. There was always a race to see who could be ready first to use it to add up the accounts, as the hand machines were so much slower