The Armstrong Family and Stoke Goldington

Henry Hilliard (better known as Harry) Armstrong was one of the great lace dealers – a showman and a real character as we shall see.

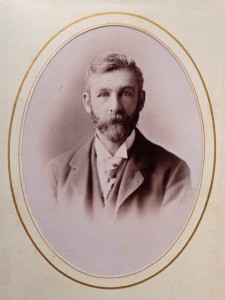

1. Charles Armstrong (Harry’s father)

The gentleman shown in Slide 1 is not Henry Hilliard Armstrong. (There are very few photos of him and you will hear my theory as to why later!) This is Harry’s father, Charles Armstrong, who was born in London in 1852.

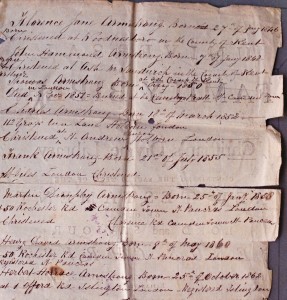

The page of the family bible recording the births of Charles and his brothers and sister is shown in Slide 2. Charles’ entry is the fourth one down (just above the black dot!).

The first two children were christened in Woodnesborough, Kent,which would suggest the family originated from there. Charles married in London though his wife was born in Hampshire. After their marriage they moved to Stoke Goldington which is four miles from Olney.

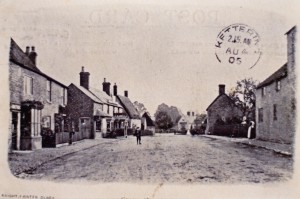

Charles Armstrong ran a grocery business from 20 High Street (the shop on the immediate left of Slide 3). Harry was of one of the eight surviving children of this marriage. His mother, Anne, died in 1894 at the age of 38 and his father married a local girl, Amy Adams, and had four more children.

The date on the postcard in Slide 3 suggests that this photograph was taken in the early 1900s.

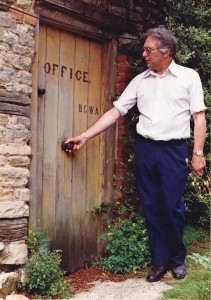

4. Bucks Cottage Workers Association Office in Stoke Goldington c. 1906

Harry’s step-mother was a lace maker – a ‘Point’ worker. Harry became interested in developing the lace marketing side of the family business, for the grocery round covered local villages in Northamptonshire and Bedfordshire, as well as Buckinghamshire. In 1906 Harry founded the Bucks Cottage Workers’ Agency from an outbuilding in their backyard. The office door still with its lettering on it is shown in Slide 4. The late David Armstrong, shown in the photograph, is the grandson of Charles Armstrong by his second marriage (and a nephew of Harry).

Harry Armstrong encouraged lace makers, who had previously given up their pillows, to take them up again assuring them of a steady market for their work.

Looking the other way along Stoke Goldington High Street, see Slide 5, the house on the left was the home of the Godfrey sisters. They were three Stoke Goldington lacemakers and, like so many other lacemakers in the local villages, worked for Harry Armstrong.

(The house was demolished in the 1960’s and a modern cul-de-sac of houses stands there now.)

The three Godfrey sisters were Mary (known as Polly), Sarah, and Esther (known as Hettie). Slide 6 shows the sisters lacemaking outside in the back garden of their cottage in Stoke Goldington. Notice their huge bolster pillows, ‘maids’ or ‘horses’ to support them, their many bobbins and their bobbin bags, pincushions, etc. The sisters were members of a family steeped in the history of hand-made pillow lace. The family was considered to be of Huguenot origin, Godefrai by name; probably forming part of the ‘Second Exodus’ who departed from Lille in 1572 and settled in Olney.

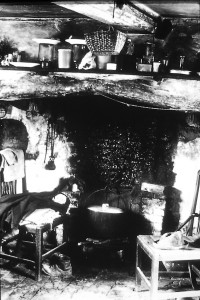

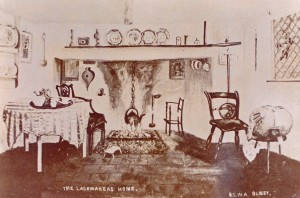

The back kitchen of the Godfrey home is shown in Slide 7. A real lived-in working room with a pot on the fire, blackened chimney, clothes and boots drying by the fire. Notice the saucers on top of the jars on the mantle piece to keep out the dust. Obviously, the ideal conditions for making lace didn’t exist in all homes!

Slide 8 is a later photograph and shows a niece of those sisters lacemaking at her home in Stoke Goldington’s High Street. I like the unusual angle of being photographed from inside looking out.

The Move to Olney

9. Harry’s Midland Road premises

Harry’s business prospered and he moved to Olney in 1909 to be near the Midland Railway with its obvious rail and postal links nationwide. Harry used these premises (see Slide 9), sited at the junction of Newton Street with Midland Road, as a warehouse for packing and dispatching postal orders, as the success of his business was due to his advertising ability.

He built a sewing room across the yard to the right of this building, where lace made in the women’s homes was sewn on to lovely sets of lingerie, etc. Everything was ‘whipped’ onto rolled seams.

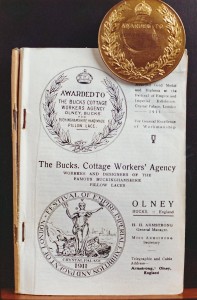

Two years after he moved to Olney, in 1911, he was awarded a Gold Medal at the Festival of Empire and Imperial Exhibition held at Crystal Palace. The award was for the Buckinghamshire hand made lace of his workers for the general excellence of workmanship. He was obviously very proud of this award and used it extensively in his advertising (see Slide 10).

The title page of a 144 page catalogue Harry published sometime between winning that gold medal and 1919 is also shown in Slide 10.

The cover of the catalogue is shown in Slide 11. From the fashions illustrated inside, I would assume it was pre First World War.

In it he states his sister Hilda, was prepared to give personal lessons in lace making, anywhere in the United Kingdom, for 2/6d (12.5p) an hour plus travelling expenses. Now the family says that not one of Harry’s sisters learnt how to make lace! If he had been taken up on the offer, he would had to have sent someone else!

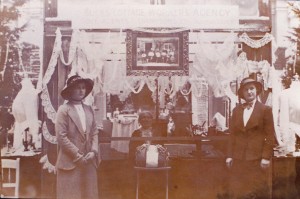

12 Harry’s sister, on the right, with a Trade Stand in Buffalo, Canada

For a larger size click the image

Through his brothers and sisters he had agencies in Australia, South Africa, Canada and India, as well as agents canvassing for him in London and Birmingham.

Slide 12 shows Harry’s sister, Hilda, on the right, with a Trade Stand in Buffalo, Canada.

A 1916 advertisement of his in ‘Fancy Needlework Illustrated’ stated that the Bucks Cottage Workers Agency gave regular employment to 600 cottage lace makers, who worked in their own homes.

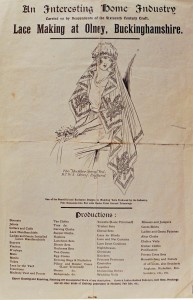

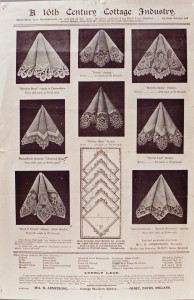

Two of Harry’s advertising posters are shown in Slides 13 and 14.

Some of the advertisements within the catalogue mention a Mrs Nellie Armstrong, or a Mrs H Armstrong. A Mrs H Armstrong is mentioned at the bottom of the ‘Handkerchiefs’ page (see Slide 14). She was neither Harry’s mother or wife – Mrs Armstrong was Harry himself – He always traded under that name thinking his customers would be more sympathetic in their dealings with a woman.

Harry never married, but he always had an eye for the ladies, and I have to be careful what I say in Olney, as he is known to have taken his female employees up the river in his punt!

Harry exploited every form of advertising, romanticising the lace industry on packaging and postcards. The picture shown in Slide 15 is taken from the lid of a box of handkerchiefs. Slide 16 depicts a cottage interior – compare that with the real thing we saw earlier in Slide 7.

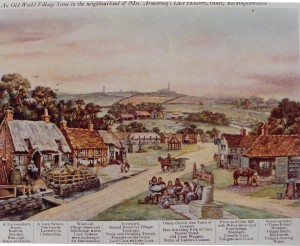

Harry even composed a romantic view of this part of the world – his ‘lace land’ – putting features from various villages into one picture! Slide 17. Thus Olney’s church stands on a hill, instead of in the valley! Turvey’s Three Fishes Inn is on the right and Harrold’s Market Cross and lockup is in the centre, as well as several other recognisable local features.

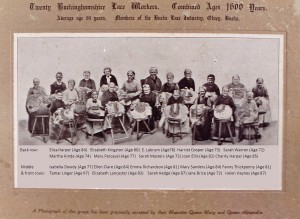

This love of ‘putting things together’ led him to employ a local photographer, Maurice Kitchener, to go around the villages photographing his oldest workers and then arrange them in a composite photograph (see Slide 18). However, this arrangement made the lace on their pillows invisible, so it was drawn in black instead!

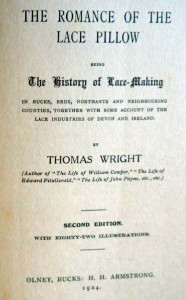

In 1919 Harry Armstrong published the extensive Lace Historians ‘Bible’ – The Romance of the Lace Pillow – written by Thomas Wright, Local Historian and founder of the Cowper and Newton Museum. A second edition, published in 1924, was even more extensive and contained 82 illustrations. The Title page of the second edition is shown in Slide 19.

Lacemaking was brought to this country by religious refugees fleeing from persecution on the Continent from the late fifteenth to the late sixteenth century. The skills were taught to the local women folk and a cottage industry of bobbin lacemaking was established.

The Lace Factory in Olney High Street

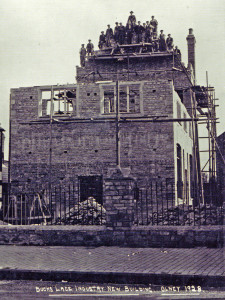

We are now into the late 1920’s and Harry’s business is still expanding and he began to look for larger premises.

A site in the High Street (now Nos 50 to 56) attracted him. Two houses, the ones with the boys outside in Slide 20, had been destroyed by fire in 1924 and the site was vacant.

The resulting Lace Factory is shown in Slide 22 and was quite pleasing considering what Olney might have had!

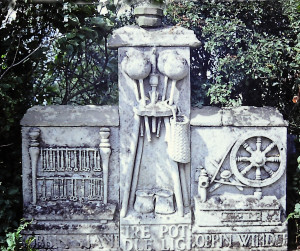

Being built in the Depression (1928) the Lace Factory was built with second hand materials. The exception was the specially commissioned carvings on the facade and over the doorway, depicting a lace maker, candle stool, bobbin winder and bobbin stand.

The carvings did not remain over the doorway for long, as they were so large and heavy and completely unsupported, so were taken down and given to one of Harry’s lady friends. Slide 23.

The carvings were re-discovered a few years ago in the garden of her former home. The Cowper and Newton Museum purchased them and had them re-erected in the museum courtyard, where you can see them today.

Harry Re-enactment of John Gilpin’s Ride

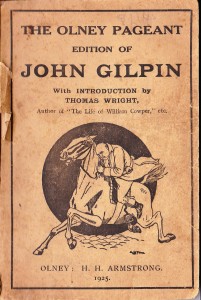

I mentioned earlier that Harry was a ‘showman’, a real flamboyant character. In 1925, he volunteered to organise a re-enactment of John Gilpin’s Ride from William Cowper’s famous poem.

This was part of a pageant put on by the Church to celebrate the 600 years since its founding. Slide 24 shows the booklet produced for the occasion. One good thing about these pageants is that they provide us with the only known photographs of Harry.

Here in Slide 25 is John Gilpin the chandler standing outside his shop (for the day – the blacksmith’s workshop next to the ‘Castle’ Inn) with his ‘wife’, ‘sister in law’ and her ‘children’. (Harry was John Gilpin, and Mrs Hollingshead and her daughter, the ladies, and the Cowley girls and their cousin Dorothy Freeman, the children.)

If you recall the poem, the Gilpins were to go off on a day’s holiday, but a customer comes to John’s shop at the last moment, so he says he’ll catch them up later. Again the scene is portrayed outside the Castle Inn. Slide 26.

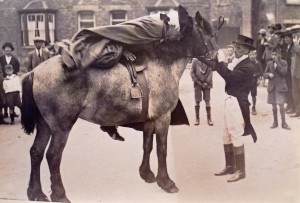

John Gilpin deals with his customer and then mounts his horse ready to catch up with his wife and family.

This delightful slide, No 27, shows the horse’s head being held as Harry mounts – NOW HARRY HAD NEVER RIDDEN A HORSE BEFORE – so small wonder that what took place next was a real enactment of the poem. The horse did run away with Harry taking him nearly to Emberton.

The horse should have stopped at the Bull – changed to the Bell for the day – in keeping with the poem. Eventually, all is well, John Gilpin does arrive back at the Bell and is re-united with his family. Slide 28.

Incidentally, the young man in the St. John uniform (without his cap!), to the right of the picture, is my father-in-law George Knight, who was to build the Lace Factory for Harry three years later.

The ‘cast’ of the ride take a well deserved bow from the balcony of the Bull – sorry, the Bell – giving us our last picture of Harry. Slide 29.

Harry’s Death and the Subsequent History of the Lace Factory

Harry travelled extensively in his business and while in Scotland in 1943 was taken ill and died on the 16th July. He was 57. He was buried 5 days later in Stoke Goldington churchyard.

After his death the Cowper and Newton Museum was given a large wall case of antique bobbins and a model of a lace maker’s lights.

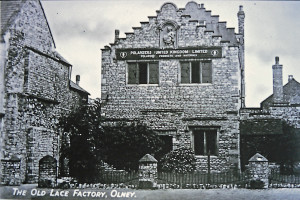

Harry’s Lace Factory was used by the Army during the remaining years of the Second World War and then used by Polarizers Ltd, see Slide 30. In the 1970s the premises were again taken over and became a successful lampshade factory. Later, in 1988, it was converted into flats and apartments.

The last, but sad tale, of the Lace Factory was told in a letter the Museum received in 1987 from a Mr Giles, a carpenter who was working for a building firm in Fenny Stratford in 1947.

He wrote:

“One day a labourer was assigned to clear out one of the sheds, and I was astounded to see what came out of the shed. There were hundreds of Lace Bobbins, and some had pieces of lace attached to them, just as they were taken off the pillow. A medallion was wrapped up with them and a box like thing was part of it. I made an enquiry as to where the lot came from and was told it was cleared out of the Lace Factory during the War. I sorted it over during the dinner break but all I could salvage was the medallion and a nice bag of beads. There were no bobbins worth saving as the damp had either rotted them, or the crowns were all cracked, a lot of them were Belgian birch bobbins, they looked as if they had been picked up cheaply. They burnt the lot after dinner. Surely I did not witness the demise of Harry Armstrong’s Lace Factory, but afterwards realised that’s just what I did”

Mr Giles sent the medallion, he rescued from the fire, to the museum. It is golden in colour, two inches in diameter and is inscribed:

‘Awarded to Henry H Armstrong for Buckinghamshire Pillow Lace’. It has a raised crown and wreath design exactly as depicted in Harry’s first catalogue, but the wording is slightly different. The illustration in his catalogue has the medal awarded to ‘The Bucks Cottage Workers Agency, Olney Bucks’, but then he could hardly run his business under the name of Mrs H Armstrong and have the medal awarded to Henry H Armstrong!

Could this be Harry’s much prised award of 1911?

And Finally!

George Knight c.1930

I will finish with a delightful tale my father-in-law told me.

He was in the office of the Lace Factory one day with Harry (who had an office built onto the side of the building later – complete with ‘fake’ inglenook).

A reasonably well to do woman came in with some lace to sell, and Harry made a great fuss of her, but after she had gone he threw the lace on the fire. Then an old woman came in with some lace, which even my father in law could tell was good, but Harry went on something alarming at this poor woman and she went out in tears.

So father-in-law said to him “What did you do that for?”

“Well, Harry said, “she is one of my best workers and I must keep her up to scratch”!!!

Apparently Harry could be a bit abrasive to work for, but because of his high standards and businessmanship, the Bucks Cottage Workers Agency flourished.

Elizabeth Knight

.

Copyright © 2015 Elizabeth Knight