The 1945 – 1960 time period comprises two parts: Part 1 Olney’s Recovery and Part 2 Leisure Pursuits. An annex to Part 1 is added to indicate some of the significant national influences on Olney life in that period. Click the links to see Part 2 and the annex to Part1.

The Post WW2 element of Olney’s social history was originally intended to be presented in four time periods: 1: 1945 – 1960, 2: 1961 – 1980, 3: 1981 – 2000 and 4: 2001 – 2020. Unfortunately the ODHS did not possess the resources to compile the three later time periods.

.

PART 1: 1945 – 1960 OLNEY’S RECOVERY DURING THE IMMEDIATE POST WW2 YEARS

.

The Two Brewers Pub displaying a very positive image in the mid 1950s

Please note that some, but not all, the photos will show an enlarged view by clicking on the image. Also that the content is divided into sections, each of which can be accessed by clicking on a subheading below:

The contents of this section are:

- Employment opportunities

- National Service

- Bank Holidays and Works Holidays

- Transport

- Education

- Health Services

- Housing Stock

- Mains services/facilities

- Emergency Services

- Entertainment

- Jumble Sales

- Sports and Recreational Facilities

- Children’s Clubs

- A Characteristic of this Period

_____________________________________________________________

.

It is important to note that that Olney’s population in 1945 was around 2000; by 1960 it had increased only to around 2400. This increase (20%) is small compared to other towns in the vicinity and demonstrates that Olney was a little slow in developing its potential.

Consequently in retrospect it is not surprising that Olney’s recovery was not exactly ‘quick off the blocks’ during the late 1940s and 50s. The major employers for men in the town were the Lodge Plugs factory, J W & E Sowman Ltd and the Cowper Tannery.

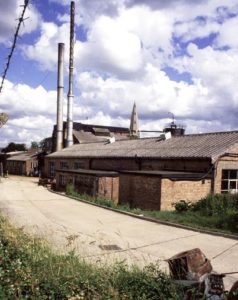

The Lodge Plugs business, that took over the Hinde and Mann shoe factory during WW11, was producing spark plugs well into the 1950s, but closed when the work undertaken at Olney was subsumed into the main production site in Rugby. The factory in Olney was located at the north end of the town (see image).

Lodge Plug Factory – early 1950s

‘Sowmans’ was primarily an ironmongery business but employed some 50 staff covering a range of mechanical and electrical engineering and building trades. The customer’s access to Sowmans was via a series of shops located on the south of the Market Place. The most prominent of those shop fronts is currently occupied by ‘Costa Coffee’. The area of the business activities was substantial; the tradesmen’s entrances being accessed via Osborne’s Court in High Street South. The staff were dispersed among the ironmongers shop, the electrical shop, the garage, the general workshop and the office. Sowmans attracted business within a 20 mile radius of Olney, including Northampton, Wellingborough, Kimbolton, Bedford, Cranfield and Bletchley. Further details on Sowmans during this post war 2 period are to be found via the link.

No 33 Market Place – Rebuilt by JW&E Sowman in 1904 as their main shop (2012 photo)

The Cowper Tannery, Chrome Tanners, Olney was situated on the town’s (north) side of the River Ouse with an access via Lime Street on to Bridge Street. It is likely that the tannery employed in excess of 150 men and women during this period.

Raw skins were always bought by weight, but finished leather was always sold by area, so the trick was to get the maximum area out of each hide without sacrificing quality. Leather was sold by the square foot in those days and output levels were of the order of 75,000 per week.

After the war the tannery continued to innovate, specialising in Aniline leather – high quality Italian skins without blemishes. Olney’s leather was much in demand; by 1990 75% of sales were for export. Despite its long and productive history the tannery closed in 1999 and the business was relocated to Billing in Northamptonshire.

The tannery site has since been redeveloped for housing.

Photo c.1986 of part of the tannery after it had closed

The tannery used the ‘Tan Buzzer’, as it was affectionately called, to summon employees at the start, mid day and finish times of the working day. At one time during this period the buzzer sounded seven times per working day at 07.00, 11.55, 12.00, 12.55, 13.00, 16.55, and 17.00 hours. Unsurprisingly the buzzer’s volume was loud enough to be heard all over the town. Its timings were so reliable that the town’s inhabitants used it as the unofficial church clock! The tannery site was finally handed over to its new owners in 1999.

The main alternatives for men were the building trade and the various forms of retailing. The wages paid by employers in the town were generally lower than equivalent jobs in the neighbouring large towns.

The shoe industry rejuvenated to some degree during this period, mainly though the application of the pre-war skills learnt by local women in the larger pre-war shoe factories, such as J W Manns and Cowleys in Olney and Drages in Bozeat. This rejuvenation resulted in several small factories being set up in the town. The factories that come to mind are Bignells in West Street replaced by Lewis and then by Crocket – Jones, Thomson in Midland Road replaced by Gola, Septimus Revet in the lane behind Midland Road replaced by R Griggs, Sudbury Wood in the High Street replaced by Lathaway, not forgetting Frank Barnes (who made football boot studs) in Clickers Yard!

Thomson’s shoe premises in Midland Road 1950s

Work in Olney for boys when leaving school was mainly confined to apprenticeships in the building and carpentry trades as there was very little else. Girls were taken on as trainee leather workers in the small shoe factories mentioned above or in retailing. The scope for trainees in office work was somewhat limited in the town.

A positive development during the 1950s was that job vacancies were starting to appear for professional and particularly skilled engineering staff and apprentices in the neighbouring and expanding larger towns, particularly Northampton and Bedford; also at local Government Establishments, such as the wind tunnel facilities at the Royal Aircraft Establishment and Aircraft Research Association at Thurleigh near Bedford, The Diplomatic Wireless Service (as it later became known) at Hanslope Park, and the College of Aeronautics (the aerospace post graduate and research based university) founded in 1946 at Cranfield airfield. In addition the banking, insurance and industrial sectors in the larger towns were also starting to post vacancies for management, secretarial and clerical staff.

Typical bus used by the Eastern National Company on their bus services from Olney to Northampton and Bedford

Most people requiring employment in neighbouring towns were expected to travel to work by public transport. Bus services were supplied by the United Counties Company to Wellingborough and by the Eastern National Company to Northampton, Bedford and Stony Stratford, noting that the existing Northampton to Bedford railway passenger service was available until 1962. Transport, some of it private, was laid on for employees at Olney to travel to the British Rail Workshops at Wolverton, the leather works at Harrold and Odell and the College of Aeronautics at Cranfield.

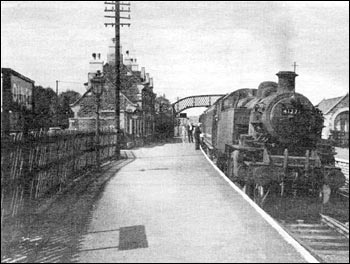

The train service from Olney to Northampton and Bedford in the 1950s

Later during this period a reproduction furniture manufacturing business was started in Olney and extensively developed in the 1950s by Stanley Woods and his family. The factory was situated behind the Bull Hotel in Hipwells former brewery buildings (now the redeveloped site accommodates the Co-op Supermarket). The reproduction furniture business proved very successful and by the 1970s had established a two storey factory outlet shop in the terraced cottages running back from Number 1 Market Place. This outlet attracted many visitors to the town, especially on Sunday afternoons. These visitors, somewhat facetiously, became known as ‘The Woodlanders’.

Typical piece of furniture manufactured in Olney by Stanley Wood

National Service had an important influence on the life of all young men whilst it was operative. It came into force in January 1949 and meant that all physically fit males between the ages of 17 and 21 had to serve in one of the armed forces for an 18-month period (which was later extended to 24 months). They then remained on the reserve list for another four years. National Service ended gradually from 1960. In November 1960 the last men entered service, as call-ups formally ended on 31 December 1960, and the last National Servicemen left the armed forces in May 1963.

National Service had a significant influence on the early careers of most young men in Olney. Although entry could be deferred for a period it could not be avoided. Therefore further education and training plans, graduate and post graduate courses, had to arranged around it.

Bank Holidays and Works Holidays

In the years after WW2 there were six statutory (bank) holidays, namely: Good Friday, Easter Monday, Whit Monday, August Bank Holiday, Christmas Day and Boxing Day Nowadays there are two more, ie: New Year’s Day Holiday and the May Day Holiday;The Spring Holiday replaced Whit Monday and the Late Summer holiday replaced August Bank Holiday.

In addition most local companies gave their employees 10 days paid leave of absence, at the employees’ basic rate of pay. In the building and construction trades, where the weather has a major influence on productivity, employees were often forced to take five of those paid leave days attached to the Christmas Holidays. Office workers often only fared a little better with, say, 12 paid days leave per year in addition to the Bank Holidays.

In this region many summer holidays were spent on the east coast, particularly in Clacton-on-Sea being one of the closest seaside resorts to Olney.

Typical ‘Oxford’ bus used on the Oxford to Bedford (via Olney) service

Public transport during this period was largely centred around getting people to work, as noted earlier in ’employment opportunities’ section, plus a few services running during the daytime. Other than that, the development of public transport affecting Olney was all but static during this period with just a couple of exceptions. The first, during the 1950s, a reciprocal arrangement between the (then) United Counties bus company (green buses) and the Oxford bus company (maroon buses) established a four times daily service via Olney between Bedford and Oxford. The second, Wesley’s buses of Stoke Goldington ran a village service from Olney via Stoke Goldington to Northampton, but perhaps of more importance to the younger population, Wesleys also ran a service four evenings a week from Stoke Goldington via Olney to the cinema at Newport Pagnell.

Wesleys (white) double deckers as used on the Stoke Goldington – Olney – Newport Pagnell (cinema) service

Cycles were used extensively by everyone, including children, as the means for local transport. The use of front lights and rear facing (red) lights on cycles, usually powered by batteries, were mandatory after dark. Failure to display a front and/or rear light was against the law and if caught would result in a (five shilling) fine imposed by the Magistrates Court at Newport Pagnell. A similar fate would result from riding a cycle on the pavement (particularly in Olney High Street!).

Among the manufacturers of cycles during this period, Raleigh were acknowledged to be the best mass produced cycles, with Hercules, probably the most popular new cycle, coming a little further down the ranking. Most Olney residents rode second hand cycles and with many being refurbished pre-war cycles. Sowmans and Minneys both sold new cycles in the 1950s. Apart from the development of accessories such as dynamos to power cycle lamps, no major developments regarding cycle technology were evident during this period.

The much sought after classic Raleigh cycle (1950s)

.

A ladies Hercules cycle (1950s)

.

There was very little (if any) local major road improvements around Olney during the period, consequently cyclists needed to take great care to avoid road accidents caused by poorly maintained roads, especially when cycling after dark.

Contrast the relatively slow development of cycles to the significant development of motorcycles. The development of small motorcycles and scooters continued on apace throughout the 1950s. Small motor cycles such as the BSA Bantam and the Francis Barnett 197cc, together with the Vespa and Lambretta scooters, proved to be the ideal low cost vehicle for commuting between Olney and its neighbouring towns and industrial estates. Naturally they also proved very useful for social visiting, reaching shopping centres and places of entertainment. Of course it wasn’t long before these commuters upgraded to larger motorcycles or saloon motor cars.

1950s Francis Barnett 197cc Motor Cycle

1950s Vespa Scooter

Although the town of Olney might have been perceived as a backwater due to both the lack of housing and industrial developments, the material prosperity of the residents during this period did improve more than one might have expected. The improvement resulted from the trend for residents to commute to work to the neighbouring towns dramatically increased. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the town’s economic well being was related more to the rapid development of UK’s domestic consumer durables, rather than to the scale of Olney’s housing, industrial and infrastructure developments.

For example, the number of privately owned cars in the locality started to increase dramatically during the late 1950s which probably coincided with the easing of Hire Purchase restrictions around this time. A time when Prime Minister Harold MacMillan’s quoted on 26 June 1957: ‘Indeed, let us be frank about it, most of our people have ‘never had it so good’. So a relative boom period?!

Most of the cars seen in Olney during the late 1940s and early 50s were pre-WW11 designed cars, like Austin 7s, Ford 8s and Morris 8s. However by the late 1950s all the major UK m0tor companies had launched a completely new ranges of styles. See the comparisons below for Austin, Morris and Ford motor cars.

Austin 7 1940s

.

Austin A30 1950s

.

Morris Series E 1948

Early Morris Minor c. 1950

.

Ford Prefect early 1950s

Ford Prefect – late 1950s

There were three garages in the town during this period, namely: Souls – an agent for Austin cars, Sowmans – an agent for Morris cars and Brocks – an agent for Ford cars. All three garages delivered petrol using gantries housing petrol hoses over the pavement to connect the (hand cranked) pumps to the cars filling caps.

During this period there were two state schools in Olney; the County Primary School comprising seven classrooms accommodating children aged 4 -11 years (since developed into The Olney Centre) and the Secondary Modern School situated at the ’top’ of Moores Hill, accommodating children aged 12 – 15 years (since developed into the Olney Middle School).

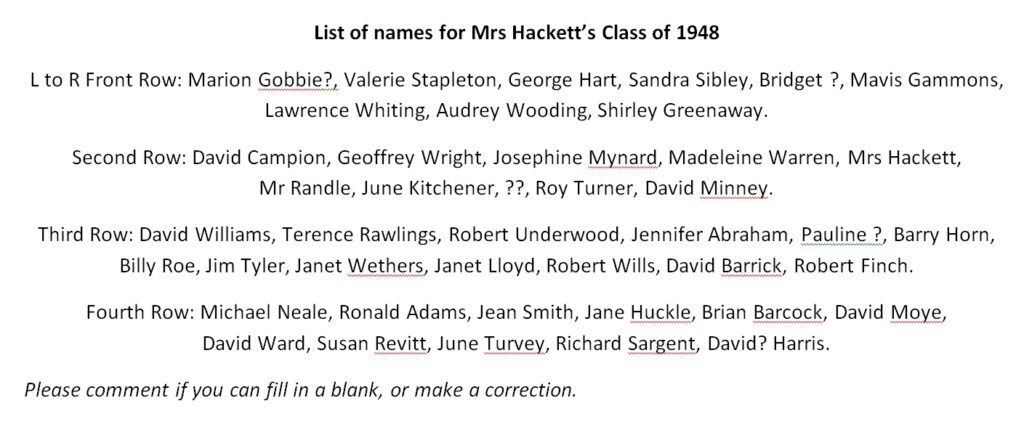

The senior class at the Primary School during during 1948, with Class Teacher Mrs Hackett and 43 children, is shown below. The Headmaster was Mr Freddie Randall who followed a Mr Packman.

Children at the Primary School were expected to sit the ’11 plus’ exam for the opportunity to attend Wolverton Grammar School when aged 10 and 11 (children were allowed two attempts). The success rate for Olney children was often no better than 10%, typically four out of forty children passed the exam each year.

Children at the Secondary Modern School were expected to sit the ‘13 plus’ exam for the opportunity to attend the Technical College at Wolverton. This school specialised in engineering subjects for boys and secretarial subjects for girls. The average pass rate for this exam at Olney struggled to make 10%.

Over the years, a few children started or transferred to the Bedford Harpur Trust Schools (essentially private schools) rather than attend the state schools at Olney and Wolverton.

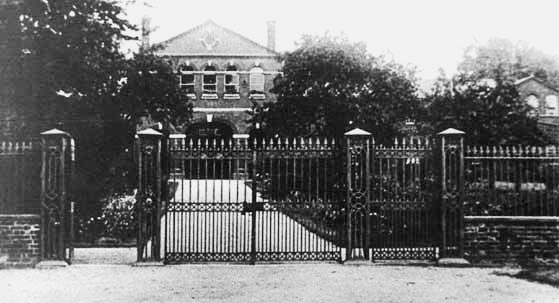

Olney had its own private school over this period. ‘St Josephs Convent High School for Girls’ was founded by the ‘Daughters of the Holy Ghost’, a religious Congregation founded in France in 1706. The school in West Street offered a comprehensive education up to the General Certificate of Education (GCE) ‘O’ Level for girls aged up to 16 years. The number of pupils in the school was 125 in 1947, and rose to 235 in 1951. Those girls wishing to attain the GCE at ‘A’ Level would continue their studies at Wolverton Grammar School or at Bedford Convent School, or at one of the two Bedford Harpur Trust Schools for girls. Boys were admitted up to the age of nine years, when they usually continued their education at one of the Bedford preparatory schools. St Joseph’s school closed on 20th July 1956. The proximity of the much larger Convent School at Bedford together with the adequacy of the public transport facilities to Bedford at the time made the decision to close St Joseph’s a rather obvious one.

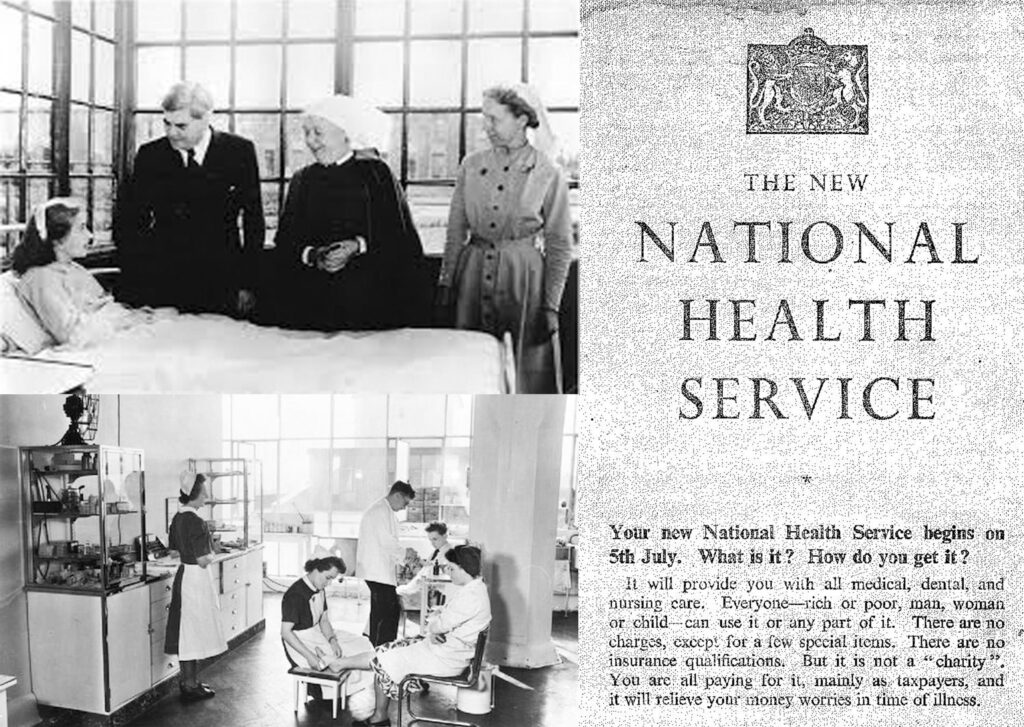

The National Health Service was launched by Aneurin Bevan on 5 July 1948 ‘to meet the needs of everyone and to be free at the point of delivery’.

At this time one doctor (Dr Dickenson and later Dr Winterbottom) and usually two district nurses (Nurse Hutchenson – Chapman when married – and Nurse Winterford, and later Nurse Crouch) were expected to service the needs of the 2,500+ population of Olney and the adjacent villages. The doctor’s surgery was essentially a two roomed single storey annex attached to the doctor’s house at 100 High Street. The room facing the extensive garden was the doctor’s surgery, whilst the room at the front was the waiting room entered directly from the High Street. As the waiting room was quite small and usually full, if you didn’t enter with a medical condition, then you probably had contracted one by the time you left!! The nurses were expected to cover three major elements of nursing: home visits and general, midwifery and welfare.

The Doctor’s House with the Surgery on its left – No 100 High Street c. 1950

Northampton General Hospital was the primary centre for accident and emergency care and covered all hospitalisation needs, whilst the adjoining Barratt Maternity Hospital was the primary centre for maternity services. Manfield Orthopaedic Hospital in Kettering Road specialised in the longer term treatment of tuberculosis and polio cases. (‘Barratt’ and ‘Manfield’ were the names of the owners of two of the largest shoe manufacturers in Northampton.) Post operation patients were often transferred to the Convalescent Home in Dallington for a few days before being allowed home.

Northampton General Hospital (say) 1940s .

.

Barratt Maternity Home Northampton c. 1940s

.

A ward in Manfield Hospital c.1950

Another maternity home used by Olney residents at this time was the Westbury Maternity Home at Newport Pagnell which accommodated lower risk patients. Also during this period a private maternity service was offered in Olney by Nurse Plackett at her home in the High Street.

Olney had two part time dental surgeries in the town, located on opposite sides of the High Street. Many school children were expected to use the free school dentist who set up a surgery about once per year in the staff room of the primary school. However, one visit to the school dentist for fillings was enough to frighten many children away from all dentists for decades!

Renny Lodge Hospital – Newport Pagnell

There were no care homes in Olney for elderly or very sick residents. Most patients in this category were referred to the Renny Lodge Hospital in Newport Pagnell which, perhaps unfortunately, was converted from the former work house! The conditions in this home were far from ideal, but perhaps its biggest handicap was its former history.

There were few housing developments in Olney during this period. The major building firms in the town were W T Revitt, McCulloch & Lett, A G Morgan and ‘Stoker’ Crouch. Revitt’s also had a substantial carpentry business in Newton Street that manufactured large caravans for fairground managers.

A Revitt built ‘fairground’ caravan on its way to be refurbished

Developments within the town was largely confined to building council houses on Weston and Dagnell Roads. Smaller developments included the bungalows at the bottom of Long Lane and the semidetached houses in Spring Lane. These four builders also had significant building contracts in nearby towns and villages.

A new gas main was laid to the town in the late 1940s in preparation for the decommissioning of the gasworks and the two gasometers in Silver Street.

Mains electricity was installed in most houses throughout the town during the late 40s and early 50s. This installation quickly brought the end of gas lighting and the misery of replacing very fragile gas mantles!

Unclear when ‘mains’ water was generally available in the town, but ‘hand pumps’ over local wells were still used in some people’s houses in the 1950s. Also, communal pumps over wells servicing small groups of houses were often used to flush (manually) outside toilets. The toilets for most houses during this period were sited outdoors in small unlit ventilated buildings, which needed to be sheltered from winter frosts.

During the 1940s and 50s a coal fire was universally used in ‘living’ rooms for heating and this one fire was often the only fire in the house. Exceptions were made for ‘high days and holidays’ when a second fire was often lit in the ‘front’ room. Although a fire place was usually built into one or two bedrooms in a terraced house they were rarely used, as they were considered as being too expensive and/or too much of a fire risk. As a child, if a bedroom fire was lit because you were ill in bed, then you knew that you were ‘very poorly’.

Rippingiles Fyrside Paraffin Heater

A new range of paraffin room heaters arrived in the late 1950s. These heaters (eg: Rippingiles Fyrside) became very popular because they were very efficient, portable and cheap to run. They were often used to heat living rooms during the daytime and used part time to heat kitchens and bathrooms. Both Turners and Sowmans used specially adapted vans to deliver paraffin direct to your door to service the increased demand for paraffin heaters.

In the 1940s many galvanised steel bath tubs were still used, usually on Friday nights, for bathing in front of the coal fire. Smaller steel bath tubs were placed usually in a stone kitchen sink the bath the children and certainly on Monday mornings ‘to do the washing’. The washing was first ‘boiled’ in a coal fired copper built into the kitchen. The washing was subsequently wrung out using a mangle in the backyard or a wringer screwed to the kitchen table before being pegged on the washing line in the back garden.

Galvanised ‘Tin’ Bath 1950s

.

Although gas and electric cookers and boilers became affordable in most households during the 1950s, open coal fires predominated as the major source of heating. Personal washing and shaving facilities remained pretty basic, often using a kettle to fill a bowl in the kitchen sink. But in the late 1950s electric razors/shavers did become more affordable and convenient to use.

The iconic British telephone kiosk

Private telephones were too expensive during this period for the vast majority of households to have them installed, but local doctors, dentists, vets and larger businesses were very dependent on them. Consequently the general public were heavily reliant on the public telephone boxes for phone communications. The cost of a time limited telephone call was four old pence (less than 2p). During this period there were only three kiosks in Olney, that is, outside the post office, outside the Castle Inn and in Weston Road at the junction with Dagnell Road.

Police : Olney Police Station was housed within No. 15 Bridge Street; a Sergeant Turney was based there during this period. Olney also had a resident police constable (PC Wood) who lived at No. 25 East Street. Police constables, accompanied by their bicycles, could often be found outside the phone kiosks, particularly the one on the Market Place or that outside the Castle Inn where they could be in communication with the local police stations or elsewhere in Bucks.

The Local Magistrate’s Court for Olney was held at Newport Pagnell.

Fire Service (to be added at a later date)

Ambulance Service and St Johns (to be added at a later date)

In the late 1940s, in households where no mains electricity was installed, radios were powered by High Tension ‘high voltage’ batteries which were relatively expensive to renew every few months. These radios also required a low voltage accumulator (a 6 volt heavy lead/acid battery) which needed to be recharged at the local radio shop (such as Minneys) every couple of weeks or so. Obviously owning such a radio in that period was quite an undertaking. A radio also required a substantial ‘aerial’ and an ‘earth’ connection. The installation of mains electricity and the subsequent development of portable radios quickly brought an end to these miseries.

12 inch? Bush TV 1954

The odd roof mounted television aerial appeared in the early 1950s. Reception was poor in Olney because the nearest transmitter was around 50 miles away at Sutton Coldfield (near Birmingham). Early transmissions were limited to one BBC channel for two hours daily (8.00 to 10.00 pm) plus an hour for children on Sundays at 5.00 pm. The numbers of TVs in people’s homes at that time, say one or two TVs per street, were not enough to materially impact on cinema attendances or other leisure pursuits, such as men popping into the local pubs for a night cap. Dances and ‘social evenings’ were popular in the town and the surrounding villages around this time, but declined over the decade.

A few years later ’traditional jazz’ bands and ‘swing band’ concerts were becoming fashionable in converted cinemas in most of the larger towns. These bands and their concerts were largely replaced in the late 1950s by pop and rock music bands. This music in turn generated a huge increase in record sales and equipment to play them, such as record players and radiograms.

There were three agents/dealers in the town that sold radio and TV equipment, namely: Field Bros & Smith, Minneys and Sowmans, but Field Bros & Smith sold by far the most records in town.

Field Bros & Smith in the High Street (1950s)

By 1960 most households owned or rented a TV which quickly resulted in the demise of the local cinemas and many of the traditional basic pubs. Many households possessed a private car for commuting to work, which also changed social habits dramatically. For example, social drinking in smarter pub lounges and out-of-town restaurants, particularly at weekends, was becoming very fashionable.

Jumble Sales were very popular during this period. Their purpose was to sell used clothes and household articles for charitable purposes. They were often, but not always, organised by church groups and held in an appropriate hall. The jumble was collected and sorted by the sponsoring group. Posters were displayed in the town to announce the opening time and venue. Entrance charges were very modest, usually around 3d (1p). Queues formed outside the hall before the opening time with the aim of picking up a real bargain!

Sports and Recreational Facilities

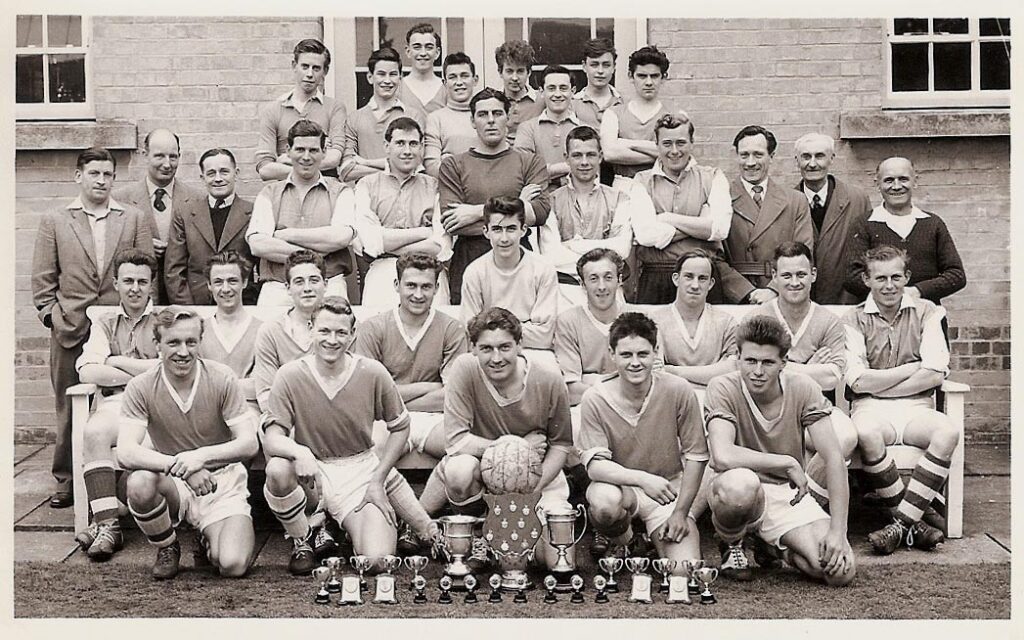

In the early post war years, Olney’s sports clubs were well established and well supported with pitches located on the river side of East Street.

The football pitch was located adjacent to East Street and the changing rooms were in a building at the back of the (then) Working Men’s Club. Arguably, during this period, the Olney Town Football Club was the most popular of all town’s sports clubs. For example, the number one ambition for most young lads in the town was to be selected to play for ‘Olney’.

The Recreation Field was on the river side of the football pitch as was the Bowls Club. The rugby football pitch was located on the river side of the recreation ground and its changing rooms were located in a building at the back of the Two Brewers Inn. Again, Olney Rugby Football Club was a very well supported club, whose popularity was to increase immensely in subsequent decades.

The rugby pitch was transformed into a cricket pitch during the summer months.

Olney Town Cricket Club, a very active club with games organised for most Saturdays and Sundays over the season. The club had a ‘scorer’s hut’ and a small band of dedicated volunteers who maintained the pitch to a high standard.

Olney Bowls Club was a well established and active club which appeared to cater for the older generations during this period. It was securely fenced which tended to give the impression that its membership was little more selective, but that radically changed in later decades.

The Tennis Club was located on the south sides of the recreation ground (in fact where it is located now). The club possessed two grass courts and a small pavilion which were surrounded by a suitably high chain link fence. During this period the membership was relatively small and any matches were organised on a friendly basis.

Coarse fishing (angling) was particularly popular among middle-aged men. The Olney fishing club was very well supported with many contests arranged throughout the fishing season along the river banks of Olney and Clifton waters.

‘Tending an allotment’ was an essential pastime for most Olney men to supplement the household budget by growing a range of fruit and vegetables throughout the season. Most allotment tenants rented a plot with an area of 10 or 20 poles. Olney had a number of council run allotment sites on the outskirts of the town; in Near Town, Yardley Road, Wellingborough Road, Long Lane and Weston Road. Consequently, annual vegetable and flower shows were very popular and very competitive.

Indoor sports such as billiards and snooker were confined to the Working Men’s Club where a couple of tables were available in a purpose built room. Table skittles, darts and card games such as whist and cribbage were played in most pubs in the town. Inter pub leagues were popular and again very competitive. Table skittles is somewhat unique as it is generally only played within a radius of 20 miles from Northampton. At Christmastime ‘Fur and Feather’ whist drives, which offered poultry and game as prizes, were always well attended.

Clubs for children during this period were far from numerous. The Cubs and Brownies intended for younger children were very popular in the 1940s as were Girl Guides for older girls, but Scouts may not have been available in Olney until well into the 1950s.

The local churches also formed children’s groups, some of which were linked to Sunday School.

An Air Training Corps unit was formed in the 1950s by the secondary modern school headmaster: Mr L Lisle Orchard. The unit was accommodated in a temporary building built in the school grounds and thrived for a good few years. A main attraction for the air cadets was the occasional Sunday visits to an air force station, such as RAF Abingdon in Oxfordshire, where the highlight of the visit was a flight in a small RAF training aircraft or an RAF transport aircraft such as a Valetta or a Hastings aircraft.

An Army Cadet Unit was also formed in Olney and was housed in a former temporary army building in Newton Street. This building was later used in the 1950s as a Boys Club and a Boxing Club, which became very popular in the early 1950s. In the mid 1950s, the Boys Club became absorbed into a Youth Club which met on Sunday evenings.

A Characteristic of this Period

After listing the Sports and Recreational Facilities and Children’s Clubs above, a characteristic of this period that should not be forgotten was the ability of children, who had few material possessions, to improvise and organise themselves. A good example of that was the impromptu football team captured in the ‘snapshot’ photo below taken around 1950.

Impromptu football team dated around 1950

Top row: David Barrick, Billy Clift, Geoffrey Wright, Richard Mayo

Middle row: Peter Hart, Robert Megeary, Terry Rawlings, Michael Ward

Front Row: Richard Sargent, Brian Marshall, Roger Berrill

Copyright © 2022 Olney & District Historical Society