The Woburn Sands Railway Station, 1846

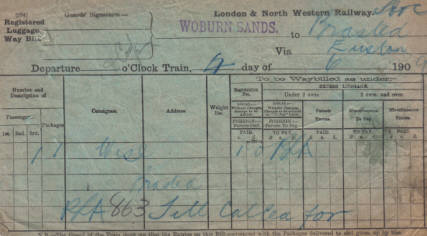

I will not be detailing the whole history of the Bedford to Bletchley (part of the Oxford to Cambridge Railway) here, but it is important to give some details as to why there is a station in Woburn Sands at all, and its importance. There are several published books on this subject and you can find the details of them at the end of this article. This page comprises of several articles by others. The images are all from my collection, and a couple from The Rail Archive, courtesy of Ian Dinmore.

The first text is a previously unpublished essay by the late local historian Arthur Parker, who spent many years researching the railway and its effect on Woburn Sands.

The Bletchley to Bedford Railway, by Arthur Parker, c.1980

The railway era commenced in 1825 – 1830, when the first lines were opened in the North of England, and from then on companies large and small sprang up all over England. It was early in 1838 before the London to Birmingham Railway opened its line to Denbigh at Bletchley, which was then described as “a small miserable village” with no accommodation for travellers. They left the trains at Denbigh and travelled to the distant towns in Midlands by coach; but the Northern section to Birmingham was finished by the autumn and the through line was opened in September 1838.

In the meantime the Directors had decided that Wolverton would be a very convenient site for their engine works, being mid-way between the two ends of the railway, the locomotives could be serviced and repaired there, a fifty-mile run being as much as they could do without inspection and possible overhaul.

In 1840 the new station was built and boasted wonderful refreshment rooms and other conveniences for the use of passengers waiting while AA engines were changed. No less than 16 women and 11 men were employed in these services; so Wolverton became an important centre, and, like Denbigh, had many coaches and mails from towns far afield making connections with the seven trains to London every day.

One of the coach services was from Bedford, and though it did not run in the direction of London, it became the favourite route for passengers to the Metropolis, as trains travelled three times as fast as coaches, and the fares were much cheaper. In 1841Northampton Mercury advertised a coach leaving Bedford at 7a.m. to connect with the London and Birmingham trains at Wolverton.

With the railway crazes at its height the townsmen of Bedford naturally thought they should have their own line, but at the time they were not ambitious enough to propose a line direct to London; Wolverton was the nearest important point, and it was to that place they suggested the railway should run to connect with the new London and Birmingham Line.

On 10 May 1844, a public meeting was held in the Bedford Rooms (the building in Harpur Street recently given up as a Library) the outcome of which was the formation of the Bedford Railway Company, incorporated under Act of Parliament. The London to Birmingham Company was approached, and asked to accept a branch running to Wolverton. Its surveyor was instructed to make an inspection of the proposed route, but Robert Stevenson condemned it, and suggested a simpler and less costly line could be run through the level to link up at Bletchley not far from the old market town of Fenny Stratford.

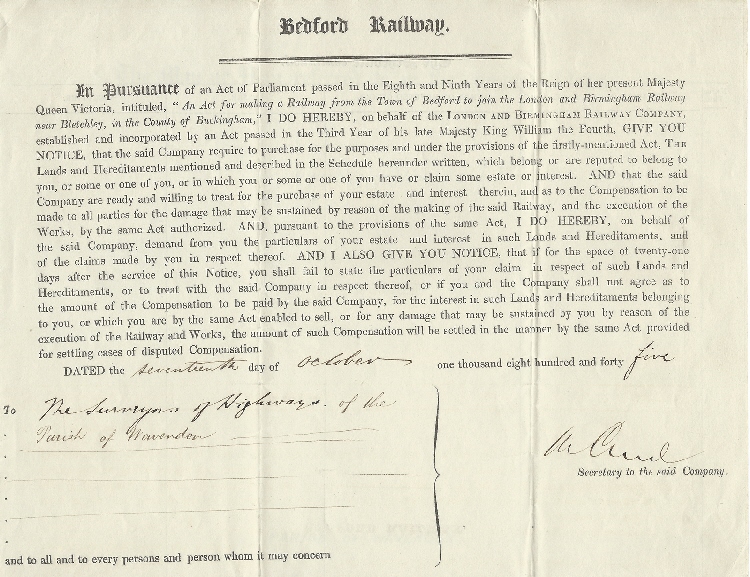

This suggestion was accepted, and the matter proceeded with. An Act for the project received the Royal Assent on 30 June 1845, and the Bedford Company shareholders met on 29 July to receive the report that the line would be constructed by the London and Birmingham Company, and that work would commence at once in order that the line could be opened in twelve month’s time.

The Parliamentary Plan and its schedules was lodged in November 1844. It shows the proposed line of railway by a centre line, with a ‘deviation line’ about 250 feet each side, to allow for alteration when the work was put in hand. Only four owners affected in the Parish of Wavendon; William Henry Denison, about 5¾ acres taken; Henry Hoare (together with land in Aspley Guise); Thomas Higgins, about 3½ acres; and the Surveyors of Highways, 1¾ acres. Mr Denison signed the plan on behalf of the Parish as “Lord of the Manor”. In Aspley Guise Parish land was acquired from seven owners.

In order the save two level crossings over public roads within 200 yards of each other, the road to Cranfield was diverted. It previously passed to the East of the Suveyors Allotment, “Gravel Pit Close” (now the Recreation Ground). This part was …osed and thrown into the field, where parts of the camber of the old road can still be seen and a new connection with the turnpike was made North of the railway, and running parallel with it.

The Bedford Company was only short-lived, and though it had a large Minute Book only four of its pages are filled. On 27 February 1846 the Directors applied for a Bill to extend the line to Cambridge, and the Birmingham Company similarly applied for a Bill to tend the line to Oxford. The last meeting recorded (27 February 1847) reports the completion and opening of the line, and that it was now vested in the London and North Western Railway Co. The Directors trusted “the inconveniences which have been complained of at Bletchley are already in a great measure and will soon be entirely, eliminated”.

There is no record of the making of the railway in the minutes of the parent company. Following the approach by the Bedford Company in 1844 it was agreed the branch be promoted. It was to be leased at a rent of four per cent on the cost, estimated not to more than £120,000, with equal division of surplus profits.

The first stationmaster at Woburn Sands was Mr. R. Snape, appointed at a salary of £110 as against his counterpart at Fenny Stratford, £80.

On 4 December 1845 a contract was sealed between the London & Birmingham Railway Company and the contractors, Samuel Morton Peto of Westminster and Thomas Jackson of Pimlico. Whereas Robert Stevenson had prepared plans and specifications, the contractors were willing to execute the whole of the work, to complete by 31 July 1846 and to keep in repair for one year, for the sum of £210,285. The specification is copied out on 35 pages of draft paper.

As could be expected, the work did not run as smoothly as it might have done. The way was mostly level (hence the number of level crossings) with the exception of the Ridgmont bank. This was constructed of the local clay earth and in consequence slipped as soon as heavy traffic passed over it; indeed it has continued to slip ever since, but not as seriously. This was the main cause .of the delay, but there were other small troubles, and after a number of announcements that the line would be opened ‘shortly’ and some acrimonious complaints, the first public train passed through on 18 November 1846. There does appear to have been much brass band rejoicing as with other lines, but I am told that, not only was there joyful excitement, but some of the women present cried, as the train passed through Woburn Sands Station.

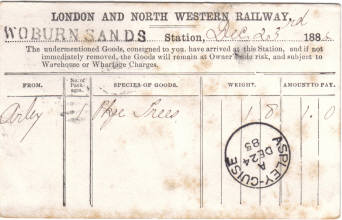

As mentioned elsewhere the quicks for hedging the Company’s boundary were supplied from Handscomb’s Nursery at Aspley Guise; and much of the ballast for surfacing the railway was taken from the pit at Aspley known as The Warren, close to Radwell Pits, for which a special siding was connected with the railway.

The second article comes from a now defunct railway magazine called Railway World, by Bill Simpson in 1986. Mr Simpson is an expert on the local railway, and has published several books about the Oxford to Cambridge Line. [I have attempted to contact the copyright owners of this article, but they have not replied]:

Railway World December 1986, Bill Simpson

On 17th November, 1846 a branch of railway was opened by the Duchess of Bedford and it ran from the youthful London & Birmingham Railway at Milepost 46½. The local company that had proposed and invested in the branch was called the Bedford Railway. As events transpired this would be the first 16½ miles of the eventual cross-country route from Oxford to Cambridge. The Bedford Railway was proposed by the civic leaders of the town and had the support of George Stephenson and the London & Birmingham Railway. Bedford had shown similar breadth of vision as had the people of Aylesbury only eight years before, and now it was possible to travel between those two county towns by rail.

The Russell family, Dukes of Bedford, had been inclined to express customary reserve at the sudden expansion of railways, a not uncommon reaction in the landed gentry. But they were at the same time inclined to evaluate developments in an astute and dispassionate way. The sixth Duke (John) had developed the commercial work of the Woburn estates by sending timber along the Grand Junction Canal at Leighton Buzzard, long before the arrival of the railways. On learning of the building progress of the London & Birmingham he had enquired as to their requirements for timber, keen to extract a good bargain.

Since 1547, the family had been a developing force in the area, and successive generations had expanded the original estate of Woburn Abbey with various parcels of land, either by marriage or by buying up failed estates. Eventually, their demesne reached well beyond the town of Bedford. The inheritance was fortunately largely maintained by the character of succeeding Russells who managed the estate with attentive skill. In particular, the seventh Duke (Francis) bought, sold, built, enclosed and drained to model standards. Even the houses built for agricultural labourers were described in the words of the time as ‘villas’, so much did the Duke believe that the retention of moral standards and efficient working was engendered by mutual respect. Ten years after the opening of the railway, he spent £832,274 from 1856 to 1875 on his Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire estates.

It would have been difficult for Bedford to have built its railway without the support of so prominent a local magnate. It would also have been less than customary for the Duke not to have seen the prospect of benefiting the returns of the estate. Most of the larchwood for sleepers was supplied by the Duke’s Housemoor Hills, Aspley Wood and Flitwick plantations. Land for the railway, including the site for the station at Bedford, was sold at £1,000 per acre; fortunately for the company this came to less than £5,000 total, to that particular landowner.

Whatever conclusions one may draw about the Duke taking no little advantage from the strength of his position, it has to be admitted that he conceded the railway the easiest route with only Brogborough Hill 1 in 29 for three miles as any kind of serious obstacle. George Stephenson’s first route, closer to Woburn, would have required piercing this with a tunnel. In the end, skirting it may have provided a gradient, but was cheaper than tunneling and more agreeable to the Duke. Woburn showed its support when the Duchess cut the first turf to begin building the line near Ridgmont station.

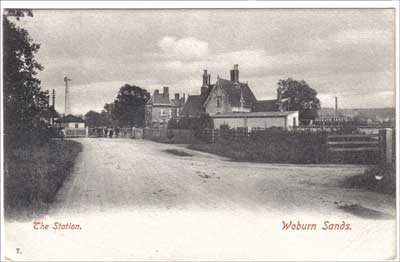

A contract for building the line was drawn up between Sir Morton Peto, along with a local builder, T. H. Jackson, and the London & Birmingham to build the line including stations and crossing houses. The remarkable result of this was that the four intermediate stations were all built in matching half-timber style, handsome black and white buildings following a gothic interpretation of cottage orne. These were complemented by the crossing keeper’s houses in brick and stone with the same decorative roof tiles. In all, a happy blend and very businesslike appearance for a railway to open with, as remarked upon by celebrated notables touring the line on the day of the first train. This contrasted markedly with the piteously frugal facilities at the junction station of Bletchley and what transpired at Bedford. The fact that the buildings were so exceptional at all must have much to do with the presence of Woburn and the existing standards there. That the company did not raise an exceptional structure to crown its achievements at Bedford was circumscribed by events elsewhere.

From the first meetings to assemble a prospectus for the line, the men of Bedford had seen this section as a precursor of the route to Cambridge, although their own capital undertaking was for this first section only. It was intended that a Bedford to Cambridge Railway company would follow, supported by the Eastern Counties Railway. Unfortunately, the enormous fraud of that self-styled railway monarch George Hudson burst upon the investment world which shook the foundations of the Eastern Counties Railway of which concern he was Chairman. In consequence, the proposed extension to Cambridge was aborted. Under financial constraints, this left the existing line with little option but to accommodate the railway in a terminus of very plain design; remaining in anticipation of restored prospects of the line to Cambridge.

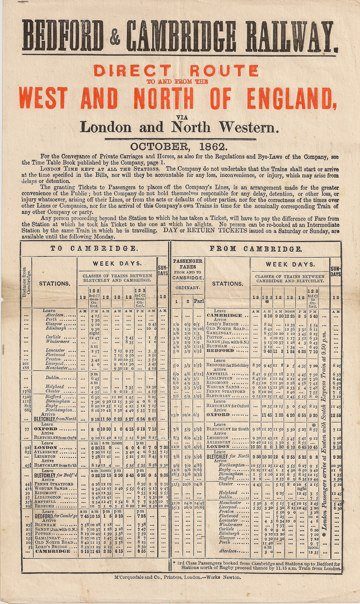

By 1862, the railway world had undergone a large number of changes in a comparatively short time. The London & Birmingham company no longer existed, nor did the Eastern Counties Railway and indeed the Bedford Railway had now become part of the London & North Western Railway. It was this company that had to be canvassed for support of a newly subscribed Bedford to Cambridge Railway which was finally opened to Cambridge station on 7 July 1862.

With the opening of the line through to Cambridge, the Bedford station was rebuilt in the gothic style, attractive if not as flamboyant and striking as the four examples on the rest of the line. How it would have appeared had everything gone to plan in 1846 must remain for thoughtful contemplation. One thing that is certain is that the LNWR station was not now in sole preserve of all of Bedford’s railway requirements, for the southward trek of the Midland Railway had brought it through the town, in prospect of reaching the capital which was first of all done via the Great Northern Railway at Hitchin. The Midland, first seeded in the mind of George Hudson, would soon steal the direction of railway interest when the impressive terminus at St Pancras was built, and so Bedford was finally located on a main line.

Returning to the subject of the early stations, the first of these was only a mile from what had been called ‘Bletchley and Fenny Stratford’. With the opening of Fenny Stratford’s own station, this was deleted from the name of the main line station. The design of stations appropriately suggests the entrance lodge to a large estate. The structure at Fenny Stratford has more closely retained its original appearance, rough cast panels with the timbering arranged with an angular vitality, the delicate fretwork of the bargeboards providing a perfect foil. A charming effect is the almost secretive peep of little dormer windows enclosed in the decorative roof tiling expansively appreciated on the steep pitch of the roof. On each side of the projecting gable are enclosed verandahs, one leading to the ticket office and waiting room overlooking the platform, the other leading to the ladies waiting room and lavatories. The gable that is the stationmaster’s house projects at right-angles, on to the approach. A repeated motif is the fleur-de-lis emblem of the roof finial which may hint at the signature of the draughtsman of this design.

Woburn was later named Woburn Sands after the geological strata of the greensand ridge upon which it stands. It follows the same pattern very closely, but here there is a suggestion of in-filling on the Bedford side of the platform gable. It is known that in 1856 additional waiting room facilities were built in this angle at Millbrook station.

Ridgmont is identical to Fenny Stratford, but has the appearance of the projecting gable thrown off balance by the addition of a ground floor window of a room that housed the block instruments.

Millbrook station is on the tenth milepost and is similar to Woburn Sands in having the waiting area enlarged in 1856. There is some association with Ridgmont which once had its signaling frame on the opposite side of the road crossing, but was moved over to the main station building in 1934 to reduce staffing. At Millbrook, the frame remained in situ as it does to this day with the instruments included in the attendant hut. This station was originally called Ampthill, but with the building of the Midland main line close to that village Ampthill had a new station and, to save confusion, the LNWR one was renamed Millbrook.

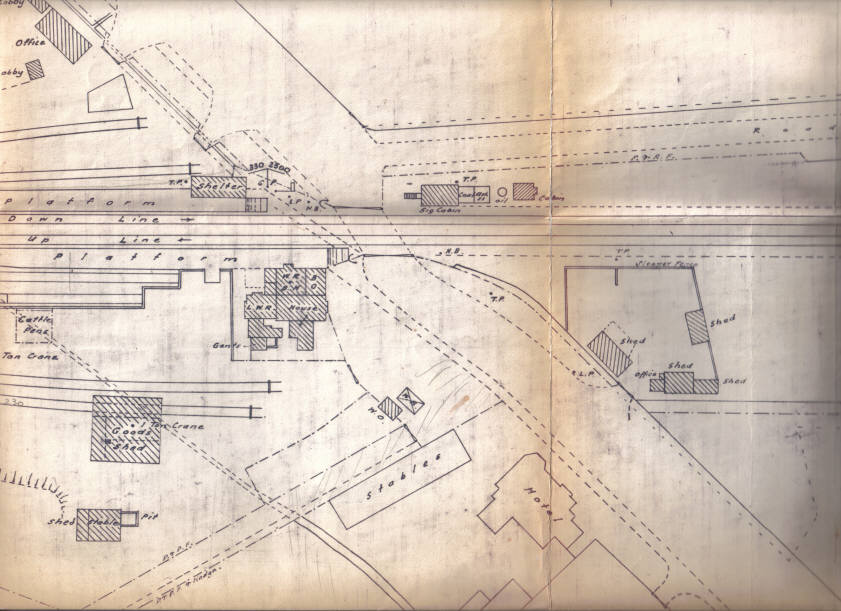

This was once a station with intense activity derived from the produce of the nearby Millbrook Brick Company – so considerable that it required five clerks at the station to administer the goods business. Special sidings were put in 100yd on the Lidlington side. At the station was a spacious goods yard with a large LNWR-style timber goods shed and brick-built stables.

Although all four station buildings are listed Grade II, maintenance has been variable. Fenny Stratford is now a dwelling only and so requires the normal attention of habitation, Woburn Sands is used by small businesses and, at the time of writing, Lidlington is up for letting while Ridgmont is still used by the signal / gateman on duty. Millbrook has been completely unoccupied for many years, and this has left it at the mercy of the elements. They have taken their toll of the building which looked likely to fall down, until recently rescued by private purchase. Dave Thomas and Alison Foreman have undertaken a prodigious task in restoring Millbrook to its former attractiveness and at the same time, they have provided a novel home for themselves.

Crossings were certainly a feature of this line with no fewer than 12 of them between Bletchley and Bedford. Each was commodiously supplied with attendant and lodge houses which brought intensive staffing levels for the line.

As mentioned in Railway World, May 1986, the Bedford line began a steam railmotor service in 1905, as did the Oxford to Bicester line. This brought into use a further six rail-level halts which in effect established 12 stopping places for all-stations trains: wherever you were along the line from Bletchley to Bedford you were near a station. For most of the period enjoying such intensity of train working, the halts were served by Webb 5ft 6in and 4ft 6in 2-4-2Ts with push-pull trains, in replacement of the railmotors. In LMS days, such workings became the preserve of ex-Midland 0-4-4Ts until LMS/BR Ivatt and Riddles 2-6-2Ts took over; in turn these were replaced by DMUs. In contrast to the Oxford line, the halts on the Bedford line survived for much longer, and indeed four of them remain open for passenger traffic. This must be unique in view of the far-reaching effects of transport policies since the mid-1950s.

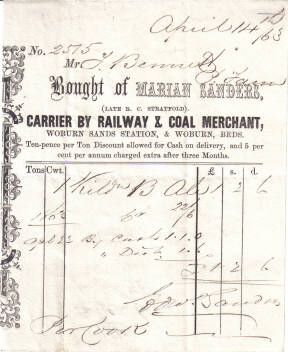

Perhaps the initiative of Woburn developed the prosperous base for communities to maintain a thrifty growth along the line. There was certainly continuing development derived from a scattering of farms until the single dominating influence on the goods traffic – the developing brick industry. The line’s east-west route ran parallel with the cross-country claybelt which was expansively exploited. First of all, there were small concerns, and a brickworks alongside the line at Woburn was almost certainly part of the commerce of the estate. Later, with large capital investment by industrial magnates, the brick industry took an enormous leap forward to large-scale manufacture, employing a method called the ‘Fletton’ process, so named after its birthplace. By this method, kilns could be built to handle four or five million bricks a week and nowhere was it more easily witnessed than along the Bedford line. In parts, the railway seemed to pass through the centre of bustling workshops with towering columns of chimneys in rows above the kilns and mountains of bricks being moved in every direction. Plants at Ridgmont, Lidlington, Millbrook, Wotton Pillinge (Stewartby) and Kempston all had sidings with brick trains marshalled into 800-ton loads for eight-coupled engines of the LNWR to draw away to meet an insatiable demand. In particular, the bricks went to the expanding network of London suburbs that had started to gain momentum after World War 1. The large volume of goods traffic and the travel requirements of the workforce saw the line prosper, in contrast to the sections to Oxford and Cambridge. At Stewartby, the London Brick Company built an entire modern village for its workforce.

Much has remained to be seen in the area. Woburn Abbey is still owned by the Russell family, retaining its esteem alongside the lighter vein of public entertainment.

As to railway interest, there is the nowadays the less common experience of travelling along a railway branch line. Many historical features may still be observed. Apart from the introduction of diesel traction the line has only begun to alter to any marked degree within the past five years. This is in some measure due to the fact that British Rail did not expect the Bedford-Bletchley section to survive a number of closure proposals. Escaping the Beeching axe allowed it to last until there were new minds at the Transport Ministry and the line managed to qualify for a government support grant. London Brick Company’s consistent use of the line with its Fletliner brick trains and Easidispose landfill trains helped to buttress strong public feeling to ensure retention of their local railway. This was effectively focused into a local group called the Bedford to Bletchley Rail Users’ Association and members have tried to keep the ‘Paytrain’ service in the public eye by organising events and delivering timetables door to door in the villages. As with so many surviving rural lines, a familiar sight is provided by the 100 or so schoolchildren who use the Bedford – Bletchley service daily.

With the building of the new Bedford Midland station in the late 1970s, the Association brought every pressure it could to persuade BR to run the Bletchley service into the new station over what had once been a goods-only connecting line. In this they were successful, and with the closure of the old station of Bedford St Johns a new halt of the same name was put in on the connecting line close by. Many of the road crossings, so much the vexation of BR, have been converted to automatic operation.

The scale of the local brick industry has diminished dramatically in only a few years, and the plants at Ridgmont and Marston have been razed to the ground. There is a certain poignancy in the survival of the Bedford-Bletchley section, with the decline of the rest of the Oxbridge cross-country line. The later Bedford to Cambridge section ceased its passenger service in December 1967 and was lifted altogether in August 1968. The regular passenger service between Oxford and Bletchley ceased at the same time, but the rails remained for freight use and many special trains have used them since. However, singling has taken place over much of this section and stations have been demolished. This leaves the first part of the through route initiated by those founding men of Bedford, remaining in regular service and so taking its 30 passenger trains a day into the line’s 140th year. Having come thus far, dare we hope that its future will remain secure? There is strong public feeling along the line that certainly wishes this to be so.

The line has its own user group, the Bedford to Bletchley Rail Users Association, who support the line and publise it. The following is from their published work, by Arthur Grigg, another expert in local railway affairs:

Bedford to Bletchley, 140 Years. BBRUA, 1986 – Woburn Sands, by Arthur Grigg The various Dukes and Duchesses were train travellers of importance. They had their own saloon which was attached at Woburn Sands to an up train from Cambridge and then at Bletchley it was placed on the rear of an express for whatever their destination, which seems to have often been Scotland. During World War 1 the Duchess was frequently seen at Bletchley station, supervising the transport of wounded officers from arriving ambulance trains on to her own road motors for her own hospital at Woburn. The same Duchess preferred flying in the days when it was not a popular means of transport and it was certainly a dangerous one. The Duke would arrive in a Rolls Royce at Bletchley station with some of his servants and then go by train to Scotland, the Duchess taking to the air. She learned to fly at the age of 61. In 1937 she took a solo flight and disappeared, never to be seen again.

On Tuesday 30th August 1910 the Woburn Sands signalman, Steele, stopped a runaway engine from Bletchley. It was not a spectacular event for him because the little ‘DX’ class engine was slowing down through loss of steam pressure. It was probably more exciting for the signalmen and a crossing keeper in between. Driver Joe Marshall and fireman, Frank Pacey arrived in No. 4 platform at Bletchley (later renumbered, 7) with the local goods train from Oxford. Frank Pacey jumped off the engine to uncouple the engine from the train, as was the usual practice. Seeing the guard walking towards him, Frank walked to meet him to get the train work sheet. Quite unknown to him, Joe Marshall decided to walk along the other side of the train to meet the guard and pick up the same work sheet. Whether the regulator had been left slightly open or it was blowing through, is not known, but the engine gently and then at a quickening pace moved away and without a controlling hand on board was seen to be merrily puffing its way towards Bedford. The signalman and gatekeeper at Bow Brickhill were all informed that the rebellious ‘DX’ was on its way and the gates at Fenny, Bow Brickhill and Woburn Sands were opened in readiness. When the engine left Bletchley its fire was getting low because it was due to go on shed and be disposed, so by the time it passed Bow Brickhill the steam pressure was getting low also, and was on the point of giving up when the signalman, Steele, climbed on the footplate at Woburn Sands. Another engine came from Bletchley to drag home the exhausted rebel. The day of reckoning came for Joe Marshall and his mate. Joe was suspended for two weeks and reduced to shed labourer, whilst Frank was put back on cleaning for six months. It did however, have a happy ending eventually when both men got reinstated to their former positions.

Life on the Railway, by John Spencer

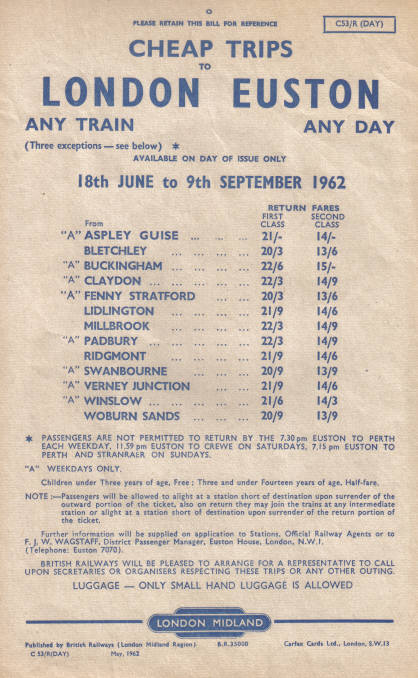

The Bedford to Bletchley line played quite an important role in my life because I was a resident of Aspley Guise until the age of 21, in 1966, and have been a life long railway enthusiast. At first I lived in Duke Street in Aspley Guise and the village station and Woburn Sands station were about equidistant from there, Woburn Sands being preferred as more trains stopped there. My childhood playmate was a cousin who lived very near Woburn Sands station and we spent many happy hours there, watching the trains, turning on the gas lamps at lighting up time and helping the porters Stan Cox and Tommy Mudd. The daily pick-up goods train was always fascinating to observe and occasionally my cousin and I cadged a footplate ride on the locomotive, shunting either by the old gas works, the coal yard or the goods yard on the Bletchley side.

My late father was also a user of the branch line when I was a child and he used to travel on the ‘motor train’ from Woburn Sands to Bedford St. John’s for many years when he worked at Taylor Brawn and Flood’s chemists shop, formerly at St. Peter’s street in Bedford. Father travelled on the same train as the school children in the morning and often complained about their boisterous behaviour. I recall father purchasing a cheap day return ticket and instead of tearing it in half, he used the pair of scissors carried in his waistcoat pocket.

Richard Clarke contacted me in May 2012:

My Grandfather was William Voss Clarke and was Station Master at Woburn Sands between 1910 and the early 1920’s. My father told me that anything that came by rail for Woburn Abbey had to be delivered immediately, and whoever delivered the goods was given a pound of meat and a pint of beer. The beer was to be drunk on the premises, but the meat could be taken away. As you can imagine, that there was great rivalry between the men at the station to get these jobs, although I believe my Grandfather shared it out equally. If it was a boy that delivered the goods, then he still got the meat, but the pint of beer was substituted for a pint of milk. I don’t know a great deal about my Grandfather, as I was only three when he died in 1949 and we were living in Yorkshire but if you do have any information about him I would be grateful. My father Cedric Cyril Clarke was signalman for a few years at Woburn Sands before leaving to continue his Railway career in various parts of the country.

The Bedford to Bletchley Rail Users Association (BBRUA) can be contacted at their website and I am very grateful for their assistance in putting this page together.

For further reading, see:

Town of Trains – Bletchley and the Oxbridge Line, by A. E. Grigg, 1980. ISBN 0860231151.

In Railway Service, The History of the Bletchley Branch of the NUR, by A. E. Grigg, c.1972. Private.

Railways in Bedfordshire, on old Picture Postcards, by Sandy Chrystal, 2000. ISBN 1900138514.

Oxford to Cambridge Railway Volumes 1 & 2, by Bill Simpson, 1981.

The Oxford to Cambridge Railway Forty Years on 1960-2000, by Bill Simpson, 2000. ISBN 1899246053.

Page last updated Dec. 2018.