This extremely long page is comprised mainly of local newspaper reports. Most of these I have copied in full rather than make notes, as they give an excellent picture of village life at that time. The fact that the vicar of a genteel village parish as refined as Aspley Guise and a local lady had such a public falling-out, over such a prolonged period and chose to use the local newspapers as the battleground, was extraordinary.

The main protagonists were:

British School and supporters

Mrs. Emily Mary Grimshawe (b.1831-d.1897) Second wife of C. L. Grimshawe, tenant of Aspley House from 1862 to 1875. The daughter of Sir Charles Gillies Payne.

Mr. Charles Livius Grimshawe (b.1820-d.1887) Tenant of Aspley House from 1862 to 1875. Educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, he was a J.P., Deputy Lieutenant for Bedfordshire and had served as High Sheriff of Bedfordshire in 1866.

Mr. John Palmer (b.1824-d.1904) Master of the British School from 1861-1873.

Mrs. Ellen Palmer (b1828-d.1935) Mistress of the British School from 1861-1873.

Mr. Thomas Gautrey (b.1852-d.1949) Master of the British School 1873-1879.

National School and supporters

Rev. Samuel Harvey Gem (b.1836-d.1926) Vicar of St. Botolph, Aspley Guise between 1869 and 1878.

Mr. John William Wall (b.1839-d.1874) Master of the National School, from c.1863 to 1874.

Mrs. Jane Wall (b.1842-d.1921) Mistress of the National School from c.1863 to 1874.

Mr. James Mumford (b.1852-d.1937) Master of the National School, then the Board School, from 1874 to 1889.

Background

Before 1870, elementary education in Britain was voluntary and left up to locals to administrate. Whilst there were Public (Private) schools which would take fee-paying pupils for those who could afford it, education of the poor lower classes was left to charities or the Church to organise. These fell broadly into two schemes: British Schools set up by the British and Foreign School Society to teach without reference to the catechism of the Church of England (and so tended to be favoured by non-conformist families); and National Schools set up by the National Society for Promoting Religious Education, who provided elementary education in accordance with the teaching of the Church of England.

There were a great many non-conformist groups in this area, with Methodists, Baptists, Congregationalists and the Society of Friends, who all wanted their children to receive an education, but perhaps not the one promoted by the Church of England. As well as the famous Aspley Academy, (a private fee-paying school), Aspley Guise had British and later National schools too. Thus, there were opposing schools, both competing for the eager young minds of the poor.

A county-wide survey was conducted in 1833, when Aspley was listed as having a “Daily School” (which had only commenced that year), as well as the private Boarding school. The Church of England Sunday School attracted 30-40 scholars, whilst the Wesleyan Methodist version attracted between 80-100.

The British School

By the side of the Square in Aspley Guise stands a small single-storey chapel building bearing a plaque announcing that it is the “Courtney Memorial Hall”, until recently used as an Evangelical Free Church. This was once used by the Aspley Guise British School.

The British school was probably established in a disused barn on the same spot as the chapel, sometime just before 1842. This was then demolished and the building you see today built to accommodate it in 1842, with a date stone on the gable end. The original barn building belonged to a local Quaker, Richard Thomas How, but it passed on his death in 1835 to his nephew William, who in turn left it to his widow Lucy in 1862.

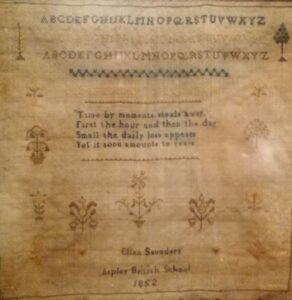

The first known teacher of the British School was John Wood, who was recorded as schoolmaster in a directory of 1850. A report made that year on the British school noted that there were 91 children present; that it was very effective at arithmetic and technical subjects, but less so at intellectual ones. The next year the inspector noted that the general plan of instruction had been “decidedly advanced since the last inspection“, with less emphasis on technical teaching though, in his opinion, the girls were doing too much fancy needlework rather than plain designs! Overall, the inspector decided it was “A most favourable specimen of a country British school“.

The 1861 census shows that John Wood, School Master, aged 36, was born in Huddersfield, Yorkshire, as was his wife Grace, 37 and daughter Mary A. Wood, 16. They lived in West Street (now West Hill).

The amenity of having a large room in the centre of the village made it an ideal location for all sorts of other events after the school day and at the weekends. The earliest reference I can find to this in online newspapers is that of 5th June 1852, when the Beds Mercury reported that a Mr. Hopcroft of Dunstable had given a lecture there on the superior advantages of life assurance over the old local benefit societies. Mr Hopcroft may have been slightly biased in his approach, as he worked for the Times Life Assurance Company and had established a local agency for them!

John Wood is still listed as Schoolmaster in the Kelly’s directory of 1854 and he also appears listed as helping with examinations at Leighton Buzzard British School in 1859, but the 1861 census showed a new Master had taken over at the school. John Palmer was 37 and from Frome, Somerset. His wife Ellen, 34, originally from Portsmouth, was also listed as a “Mistress of British School”. They had one daughter, Fanny, who was 19 months old, born in Alresford, Hampshire. He is mentioned in a Beds Times, 11th March 1862, report about the school:

“ASPLEY GUISE. On Friday, the 7th inst., a tea meeting was held in the British school-room, Aspley, for the purpose of bringing together the parents of the children to hear the examination conducted by W. Milne, Esq., of the Borough-road Establishment. In the absence of G. Clayton, Esq., B. Wiffen took the chair, who, having briefly explained the purport of the meeting, introduced Mr. Milne, who questioned the children upon reading, geography, mental arithmetic, &c. The questions upon each subject were answered very correctly; the reading was especially good; and the readiness with which the answers were given in mental arithmetic showed they had been well taught. After the examination of the children the report was read, showing a balance in favour of the school of £1 8s. 7d., after paying for some considerable alterations for the improvement and accommodation of the children. Mr. Milne then addressed the parents upon the advantages of education, and the good results derived from sound moral principles being instilled into the minds of youth. Mr. Palmer, the schoolmaster, also addressed the audience, and especially called upon the parents to see that their children were sent regularly to school, as much of the success was descendant on the parents as well as the master. The tea, which was of the best quality, was done ample justice to by the numerous attendance of parents and friends, and the public meeting was also well attended, the company being highly satisfied with the condition the school. At the conclusion the old song of “Don’t Fret” was sung, and the meeting broke up.”

Cravens trade directory of 1863 still gives the previous British Schoolmaster’s name, but sometimes these trade directories used previous edition information without checking very thoroughly. However, it also gives figures of average attendance: “British School, J. Wood, master: Number of boys, 70; girls, 30.”

Palmer obviously had strong views on the national education system question. From the Northampton Mercury, 14th December 1867:

“Elementary Teachers’ Association. On Saturday last the tenth quarterly meeting of the Beds and Bucks Association was held at the British School room. Mr. J. Palmer, of Aspley Guise, read a very interesting paper on “English Provincialisms,” which was followed by an animated discussion. Afterwards the meeting took into their consideration the relation of elementary teachers to the present aspect of the educational question; and it was deemed advisable that all teachers as practical men should give public expression to their opinions upon Educational Reform.”

The National School

A National school was opened in Aspley Guise in 1848. This was a short distance up Woburn Lane, south of the Square. They had advertised for a new master for it in the Northampton Mercury in November the previous year.

“Aspley Guise. Wanted, for the National School, at Aspley, a Master and Mistress, who are competent to teach upon the National System, and who are members of the Established Church. Applications, with references as to character, to be made to the Rev. J. Vaux Moore, Rector of Aspley.”

The Government had insisted that schools which received government grant monies should be inspected. This was resisted by the Church of England, until a compromise on inspection by clergymen was reached. Two years after opening, Aspley Guise National school was surveyed by Rev. F. C. Cook, who reported:

“Aspley Guise Boys, 1st July 1850. 213 present. 1. Desks and furniture: Good; convenient and well-arranged. 2. Books and apparatus: Not sufficient supply of easy reading books nor of slates. 3. Organisation: Two school rooms in each, the instruction is conducted with great care and industry, by a teacher and assistants. 4. Instruction and discipline: May be much improved in the boys’ school. 5. Methods: The teaching in the boys’ school is too mechanical. 6. Master and Mistress: The master is a very respectable and conscientious man. I also think well of the intelligence and industry of the mistress. 7. Special: This report represents the two schools as one mixed school. Many subjects of instruction are common and each teacher takes part in both. The school is efficient in many points of great importance – the numbers have increased rapidly and regularly, and the children are well instructed in most elementary subjects, while some have made fair progress in the higher subjects – but great improvement in discipline and method of teaching will be requisite to justify the continuance of the three pupil teachers, after the next annual examination.”

A year later, the same inspector returned and his report said that whilst an abundant supply of good books and maps had appeared, he had now decided the furniture was now not suitable! “The desks are not convenient, but they cost much money, were approved by the Committee of Council when the school was built and could not be altered without great expense”. It was a different inspector in 1853, who mentioned that the master and mistress were Mr. and Mrs. Ellen and commented “There is much real and hearty work in this school, and I can speak of it in terms of high commendation.”

The Ellen’s are recorded as still in charge in 1854, but by 1861 the schoolmaster was listed as Mr. Webb G. Humphries. He lived in the house next door to the school, with his wife and two children. At the same time, nearby in Fenny Stratford, Mr. John William Wall was a boarder at a house. He was a single man, described as a schoolmaster. He married a Wavendon lady called Jane Sollom in 1863 and would soon become an important figure in the local National school history.

Cravens trade directory of 1863 was also out of date for this school, still giving Charles Ellen, as master. The numbers they gave as attending were 90 boys and 50 girls.

The earliest reference in the press to Mr Wall (of Fenny Stratford in 1861) having taken on Aspley Guise National School is in 1868. The Beds Mercury reported in November that the school had given a testimonial to Rev. Hay Erskine who was leaving for Long Marston. There were songs and recitations from the scholars and they presented him with a blotting book, a book-slide, a letter-weighing machine “in coromandel wood set with ormolu and Wedgwood cameos” and an illuminated paper with illustrated border of wild flowers made by Mrs. Wall, as they were then in charge as Master and Mistress.

In 1869, a new vicar, Rev. Samuel Harvey Gem, took over at Aspley Guise. The son of a Lincoln’s Inn solicitor in London, he had grown up living with his grandfather in Sion Hill, Wolverley, just north of Kidderminster. He studied at University College, Oxford, (where he won the Ellerton Oxford University Prize for best essay of the year in 1861, on “The state of religious belief among the Jews at the time of the coming of Our Lord”). After attaining his M.A., he was married to Louisa de Berniere, daughter of Rev. Newton Smart, of the Prebendary of Salisbury, with the service being conducted by the Lord Bishop of Salisbury in August 1865. They had a daughter in 1866 and a son in 1869 soon after coming to Aspley Guise. Rev. Gem took a very keen interest in the National School and the national education system as a whole.

1871

So both schools arrived at the 1870’s with prospering fortunes and a good attendance. Rev. Gem, although having his own National school to support, was not above coming to the British school to access the scholars, so there must have been a good spirit of co-operation between them. From the Beds Times, 25th Feb 1871:

“ASPLEY GUISE. This village last week was the scene of two interesting juvenile gatherings which, though not partaking of the outdoor amusements that the summer season permits, we yet desire to chronicle. The first in order was a tea given to the children of the British School by Mr. Letchworth, and of which Mr. Palmer is the highly efficient master. The results of his training were practically evinced in the examination that took place afterwards, when we would particularly specify the rapid answers given by the children in mental arithmetic and their excellent knowledge of geography. Mr. Harvey Gem, the rector of the parish, examined them in the Scriptures, and praised their proficiency. His presence on the occasion and his address to the parents best testify to the interest he takes in promoting the cause of education under whatever designation it may be promoted. There were also present Mr. and Mrs. Grimshawe, Mrs. How, Miss Thorpe, Mr. and Mrs. Dymond, Miss Letchworth, &c., &c. Then on Friday took place a meeting of the children of the National School to receive the presents suspended from a beautiful Christmas tree given by Mr. and Mrs. Gem, and which we regret her illness had prevented at Christmas. Mrs. Gem, we are happy to add, was able to be present, and we observed also Mrs. Smart, Rev. Hay Erskine, Mrs, and Mrs. Grimshawe, Mrs. Hugh Jackson, Mrs. Carlisle Parker, Mr. and Mrs. Dymond, Mrs. Trew, Miss Tattam, &c. The singing of the children in the various pieces was much admired, and the modulation of their voices very good.”

There followed the lyrics of a song, “The Christmas Tree”, composed by the school mistress for the occasion.

By the time of the 1871 census, the Palmer family had expanded to include daughter Emma, 9 and sons Fred, 5 and John, 2. There were two other children in the house described as ‘Boarders’; William Palmer, 4, from Linslade, Bucks. and William Faulker, 10, from London.

Also in Aspley, nearby in Woburn Lane, were the family of Mr. Wall, Master of the National School. John W. Wall, 32, was born in Tetbury, Gloucestershire but his wife Jane, 29, was from Wavendon. They had married on Christmas Eve 1863. Daughter Emily, six and son Harry E., not yet one, were both born in Aspley. Frederick Dickens, 14, and Alfred H. Davis, 13, were both described as Boarders. They also had a servant, Ruth Collins who was just 12. The Wall’s had to deal with a horrific accident at the National school in April, when a tall gymnastic pole erected in the playground toppled over and killed Julia Bunyan, the 14-year-old daughter of the local plumber and painter of East Street. Although looking perfectly serviceable from the outside, it was later found the timber had rotted away in the middle. The coroner ruled it an accidental death with no blame on anyone. School was suspended for two days and Mr Wall wrote in the school log-book “Distressing and fatal accident in the play ground Julia Bunyan instantaneously killed by the falling of the circular swing post.”

Change eventually had to come to the factional nationwide education system. The Elementary Education Act of 1870 was the first of a number of Acts of Parliament passed by the Government between 1870 and 1893 to create compulsory education in England and Wales for children aged between five and 13. Not only did this guarantee an education for the children, it stopped them being used as cheap labour in dangerous occupations. This led not only to arguments about who should pay for such a scheme, but also an inevitable power struggle between the opposing sides of British and National schools and their belief systems, as each wanted to be in charge locally. It was easy where only one school existed, or where one had a far greater attendance than the other, but in Aspley it was split fairly evenly in numbers. It appears neither side wished for the local arrangements to be handled by a voted-in School Board, as they would have lost overall control. This set the scene for an interesting stand-off, not only between the adults, but sometimes the children too. The friendly terms between the Aspley Guise vicar and British school were soon a distant memory…

The first report seems innocent enough. Someone took the initiative and decided to bring the two sets of children together for a late-summer fayre. The National school had had summer fayres as far back as 1850. What could be jollier than a joint-schools fete, held on neutral territory? The Grimshawe’s were tenants of Aspley House, where they lived with their three children, a French governess and five servants. From the Beds Times, 5th September 1871:

“Village Fete and Garden Party at Aspley Guise. On Friday, Sept. 1st, Mr. and Mrs. C. L. Grimshawe invited the whole of the children of the British and National Schools with their parents and friends to a festival, which was held in the grounds of Aspley House. A large number of the clergy and gentry accepted the invitation to a croquet party, which was held in the gardens on the same occasion. The children, to the number of about 220, assembled at 1.30 p.m.at the Obelisk on the Village Green, which was gaily decorated with flags, and after being marshalled into order were marched to the grounds, headed by the Aspley band, and preceded by the Rev. Mr. Isaacs, Mr. Whitman (churchwarden), Messrs. Pickering, James Turney, Ardley, W. Harris, Joel Perry, Charles Inwards, D. W. Wooding, and Goodman (members of the School Committee), and Mr. Palmer (the master of the British School). On entering the grounds the procession was received and welcomed by Mr. and Mrs. Grimshawe, both on horseback, when Mrs. Grimshawe delivered the following spirited address from the saddle: – Gentlemen of the Committee and Children of the British and National Schools, On this the first occasion of your meeting in these grounds, the first occasion, too, I believe, of your different schools meeting at a combined village fete intended equally for each, I wish to address to you a few words of welcome and some short observations suggested by the occasion. I have just described you as different schools, yet that is not a sufficiently clear definition, unless we recollect that there is such a thing as “a distinction without a difference”. All schools now under Government inspection are regarded as “British and National Schools,” and under the new code are subject to the same Government inspection and are accorded the same Government patronage regarding grants. In the Nation’s Schools I believe the Church Catechism, which constituted the original distinction, is now no longer insisted upon, and I think it is rightly so, for, whatever truth that catechism may contain, I think, with many others that it is certainly not a compendium of the Christian religion. There is one book only which can lay claim to that title, the Bible – and the Bible alone – and this is equally taught in both British and National Schools. Some are of the opinion that no one school would be sufficient for this village, while others there are who say there are as many as a hundred of the village children who attend no school whatever. I would ask those who are aware of this fact whether they think it probable that school attendance would be promoted by the extinction of the British School – established 30 years ago, the very first, when no other school existed here; I was never more astonished than when informed of its projected abandonment for want of funds. I attended the meeting at which the question was discussed, and I and several others immediately offered to double our subscriptions. I am glad to say that before the meeting broke up a new committee was formed of the leading tradesmen, who, rejecting all idea of its abandonment, forthwith voted the enlargement of the school with an additional class-room and its entire reconstruction (regarding accommodation and discipline) under its present valued master. I have known Mr Palmer now some time, and from many conversations with him on the subject of popular education I have ever found him a man of clear and liberal views – understanding the art of imparting knowledge and very earnest that such knowledge should be based on religious principles – not the distinctive tenets of any sect, but the broad principles of Christianity. I am a churchwoman myself, from a conviction as well as early education, and a member of the Church of England and I hope I shall always remain. Many of you, I believe, are not; yet there is common ground on which we can all meet – of membership in the Catholic Church of Christ – no matter by whatever name we may elect to be distinctively known; but I must not now enter on this extensive subject. Of the National schoolmaster, not here, I wish to say but little; I have tried to interest him and his wife in our gathering here today, but I regret to say without success. What I hoped I might turn out to be the means of bringing about a better understanding, has consequently resulted in an exhibition of feeling which it would be more desirable to consign to oblivion than to be further alluded to here, his scholars are here – he is absent, let him now therefore be “out of sight, out of mind.” Mr Grimshawe and myself in welcoming you here today are desirous of publicly showing you the interest we take in the education question; under whatever name such education may be advanced. Your country has pronounced, and from one end of England to the other it has gone forth, that the people must be educated, and that such education is not merely to be secular but that the Bible shall be the test book of her national religion – enforced on none, offered to all. We bid you all heartily welcome to the fete and I beg you observe three banners under which you assemble, respectively, “Education Fete” – “Read and Write Club” and “Peace on Earth, Goodwill to Men”. The education that we hope to promote is best symbolised by the large “Ivy Cross” from which you first started here today. The Christian religion is the only basis of real education. The being able to read and write well is the elementary machinery of all knowledge, and the spirit in which we all desire to meet today is that of “Peace on Earth, Goodwill to men.” The flags are also symbolic colours, red, white and blue – white symbolises purity and truth; red – determination (and I trust in the right path); and blue – hope, the colour of the heavens to which all our hopes ascend. Symbolic language is I think impressive, and I have translated mine that it might be rightly interpreted.

It is of course impossible to reproduce in print the clear enunciation, the vigorous, earnest style, the sweet intonation, which characterised the delivery of this address, as it is also equally impossible to paint the impressive action which accompanied the words as they fell from the lips of the graceful equestrienne. It was listened to with deepest attention throughout, and loudly applauded. After the delivery of the address the children and their friends set to work to make the most of their holiday, and enjoyment soon became the order of the day. The tents and gateway and the church tower adjacent were gaily decorated with flags bearing severally the following mottoes: – “Long Life and Happiness”, “Education Fete”, “Read and Write Club”, “Peace and Plenty”, “Peace on earth, Goodwill to men,” & c. The band was playing, the bells ringing, here was trap-ball vigorously carried on, there football, there again a croquet party; over yonder was a time-honoured aunt sally; further on a large party at French romps; opposite were a group of the younger visitors running, skipping, jumping, rolling, laughing, romping, tumbling and generally enjoying themselves to the upmost by “threading my grandmother’s needle” until four o’clock approached, when the buns and tea and cake attracted the majority to the tents for refreshment. The first tea was supplied to about 350 in two tents provided by Mr. Lilly of Woburn, the tables being ornamented with bouquets; the second supplied about 50 or 60 more. The little folks were kindly attended and waited upon during tea by the committee, with the misses Grimshawe (under the care of their Governess) at their head. In the garden meantime the croquet party was proceeding. Mr Wilshaw’s Quadrille Band being in attendance. Refreshment were provided in a tent on the lawn and were freely partaken of.

… After tea the children, accompanied by Wilshaw’s Band, sang the exquisite melody, “O Paradise, O Paradise,” with most delicious effect. The sports were resumed until about six o’clock, when several balloons were sent up, to the great amusement of the juveniles. A variety of prizes having been distributed, dancing was continued until the shades of evening gathered around the festive party and gave the signal for departure.”

Under that news report was a letter addendum from the Grimshawe’s:

“THE VILLAGE FETE. The fete given at Aspley House on Friday last to the Committee and Children of the British and National Schools and the promoters of education generally is intended, should circumstances permit, to take place annually. Next year it will probably be fixed for an earlier day during the months of July or August. At this fete, given in honour of education and for the enjoyment of the people, the game called Kiss in the ring will under no circumstances whatever be permitted, and is absolutely prohibited. Everyone who thinks twice will see the reason of this, in the highly objectionable character of the game. The freedom and licence it allows are destructive of good manners, and too generally conduce to conduct that is morally wrong. What real enjoyment is there in pleasure that we feel we cannot look back upon with satisfaction? What real enjoyment is there in any recreation that, instead of better fitting us for our work in this world, only leads into temptations that unfit us for life in the other world In England now, at all properly organized fetes, whether private or public, this game is forbidden by all those promoting the healthy enjoyment and recreation of the people. There are many other English outdoor games that all can join in with pleasure and satisfaction instead of “Kiss in the ring.” We will have a “dance on the green,” to music that all can listen to with delight and all take part in who desire. Let us at Aspley have education (at least to such extent) that it may everywhere be said, “All people at Aspley know how to read and write.” Let us at Aspley have such recreation as may everywhere be said, “The people of Aspley know how enjoy themselves. Let us at Aspley have such conduct as may everywhere be said, “The people of Aspley (by whatever name they like the call themselves) are Christians.” E.M.P.G.”

A laudable idea surely? It seems an idyllic fun-filled British summer fete had been had by all. All, that is, except the two people who had apparently refused the invitation to attend… the Master and Mistress of the National School, Mr. and Mrs. Wall.

After the next Sunday service at St Botolph’s, where two sermons were preached for the benefit of the National School, the Beds Times reported that a note had been found in the collection plate:

“There are two parish schools in this village,

Both acknowledged by the Government of our country,

Both, I hope, fulfilling their mission of usefulness.

The one, poor — by some despised and rejected;

The other, rich — by many patronised and supported.

To the first, my sympathies as an Englishwoman belong;

To the last, my contribution as an individual is small;

To both, as a Christian, I must wish success.”

To me, that sounds very similar to Mrs. Grimshawe speech from the fete, so it appears she, or perhaps someone close to her, was having a further dig at the National School.

Mr. Palmer, of the British School, was a keen photographer and was obviously on good terms with the Grimshawe’s. He attended their house in November the same year to give a dissolving lantern show of comic scenes and astronomical images. He returned a week later with his whole school science class, when he delivered a lecture on “Electricity and Magnetism”, to which Mr. and Mrs. Grimshawe attended with their children. He also had an engagement to perform the same lecture to Baroness Mayer de Rothschild at Mentmore. Mrs. Grimshawe also had an interest in photographs and projecting lanterns.

1872

Just into the New Year of 1872, she loaned her equipment to the British School for an entertainment in their hall. The Beds Mercury of 13th January, said, “the photographs were most artistic, and the comic scraps and chromatropes were welcomed with shouts of delight from the juvenile audience”. About 140 sat down for tea and singing. The article went on to describe the history of the hall, the school and the budget, in a very pro-British School piece:

“It may not be out of place if we, on this occasion, lay before our readers some information regarding this school, the oldest parochial school of the village. Built in 1842, at a time when none other existed, it has gone on steadily pursuing its educational work. During the mastership of its present master, nearly 700 scholars have passed through the school, the majority of whom are occupying most respectable positions in life, some ministers, some clerks, some schoolmasters and schoolmistresses themselves. Not later than a fortnight ago 70 of these old scholars, at their mutual desire, met together at the British school and spent an interesting evening, recurring to their past life there, and their present happy prospects that one and all felt were owing to the care bestowed by their former master, which must have been highly gratifying to him, and at the same time satisfactory proof of the success of the British school system. Last year, owing to failure of funds, the school was on the point of abandonment. It was felt with adequate support this ought not to be, and Mrs. Grimshawe, whose interests in the education of the working classes is well known, threw life and energy into the movement. The Government had in great measure adopted the principles of the British school system and the Elementary Education Act, giving a stimulus. A new committee was formed who decided according to its requirements to considerably enlarge the school, which now we believe is the largest in the parish. How it is to carried on remains to be seen, for in the parish of Aspley Guise there are two schools, the British and the National, now equally dividing the education of the place, each of them having the same number – about 100 scholars – in daily attendance. The great difference of the two schools being by the last report, that while that of the National is carried on at the expense annually of £179, that of the British with the same number of scholars has only £85 per annum to meet all expenses. The salary of Mr. Palmer, a certificated master, has consequently been reduced from £70 per annum to £25. It is estimated that besides these 200 children there are nearly 100 more who attend no school whatever. How long this state of things will last, whether the solution of present difficulties will be only be in a schoolboard, the future will decide. Those who deprecate such a solution will have only themselves to thank for the dogmatic spirit in which they have endeavoured to carry out the Act, instead of softening difficulties and amalgamating the exertions in the important matter of national education, has aroused throughout the country a feeling of sectarian bitterness, of which, as Professor Jowett says, the little children are the victims. Those who dislike a school-board, from the fear of rates, should calmly examine the subject for themselves, and not be panic-stricken by the prejudiced statements of others, but work out for themselves the simple problem, using homely adage of whether prevention may not be better than cure; whether by the blessings of national education the chances of temptations to vice and crime would not be considerably diminished whether in a word an education rate would not considerably decrease the national tax which we have now to pay for our paupers and criminals. To those who regard school-board looming in the distance with feelings of satisfaction, events appear fast hastening when compulsory education must become the order of the day; then only can ignorance cease, and the people no longer perish for the lack of knowledge; and the day is probably not far distant when elementary education shall be free, when such education shall not necessity and quibble, but the free inheritance and legal possession the whole English people.”

Another rousing speech which may have come directly from the pen of Mrs. Grimshawe? This latest attack on the costs and (suspected) blinkered view of the coming Board system by the National School could not go unanswered, but it was not the National School master who wrote in in defence the next week, it was the vicar of Aspley Guise himself. From the Beds Times, 23rd January 1872:

“ASPLEY GUISE. Sir, l have observed in your paper during the past summer several communications respecting the Aspley Schools. I have thought it better pass these over, being anxious to avoid all chance of controversy; more especially as the British and National Schools have for many years lived on terms of peace and amity, a state of things which I have earnestly endeavoured to maintain. But an article communicated to your last impression is calculated to give an erroneous view of the condition of parochial education in Aspley (St. Peter). It is stated that nearly 100 children in that parish attend no school whatever. But the same article makes the number at the British and National Schools to be 200. Now the population is 962, and the Government rule is that one-sixth should be under education; 160 therefore is the number that should be at school, but the article admits 200 be there. The excess might be supposed to be due to children coming from other parishes, but these are in no great number, and the necessary inference is that the parish children attend tolerably well. That this is so was proved a year ago by a house to house investigation by my curate and myself, conducted for this special purpose. The number on the books the National School was the last return 105. Its master and mistress are each certificated; there are two pupil-teachers and a pupil-monitor. Everyone who knows anything of parish schools knows that 100 children – boys and girls cannot be disciplined, taught, and trained in at all a satisfactory manner with teaching power of less amount than this; and in fact with less power than this any inspector will say that the teaching and discipline must necessarily be inefficient. The sum earned Government by good examinations and attendances was £65 including £5 1s. 8d. for the Night School, and the Inspector’s report was highly creditable. Nor should it be omitted that the National Night School has a full average of 20. Your correspondent, taking the last year’s accounts only, asserts that “the National School is carried on an expense of £179 annually.” This is not so. A heavy charge for repairs and another increased item raised the ordinary outlay (which is about £165) to higher sum than usual; and I may appeal to all who understand the matter, and to the authority of Mr. Forster himself, whether a really good school is not reckoned to cost 30s. a child: indeed on that calculation it is that 15s. child, or 50 per cent., is allowed by Government for those children who fulfil the conditions. For 105 children the whole cost would thus be £157. If we exceed this it is to be remembered that the expenses of the Night School are included in our annual total. The writer, I must observe further, is inaccurate in regard the size of the National School-rooms. Having been built originally for Crawley and Woburn Sands as well as for Aspley, the school space, according to the requirements of the Privy Council, is sufficient for all and more than all the children of school age in Aspley (St. Peter). To free the British School from its “difficulties,” (of which, I should say, there may be other solutions,) your correspondent advocates a School Board. The parish can hardly desire to incur the expense of one to bear the cost of salaries to treasurer, clerk, rate collector, and beadle – to encounter the disputes and bickerings and party divisions inherent, apparently, School Board – to throw away the liberal voluntary contributions which now save the ratepayer from an increase to his already heavy burdens, and to reject too, along with those contributions, the kindly feeling which it is the privilege of schools voluntarily tended and cared for enjoy; and as to the compulsory power of Board, I think the parish will ask if it be wise to give up positive advantages and incur certain evils, when the value, operation, and efficacy of compulsion are yet in doubt. The supposed “dogmatic spirit of certain parties” elsewhere has no counter-part in this parish. It is well known here in how thoroughly friendly a spirit I have endeavoured to act towards the British School; and how, considering nearer connexion with the National School, I have gone out of my way on many occasions to shew my readiness to co-operate with the supporters of the other school on the broad ground of Christian good-will and unity. There has been nothing therefore in the conduct of the clergy to give occasion for a Board School.

Your obedient servant, S. HARVEY GEM. Aspley Rectory, Jan. 16.”

The vicar had to write in the next week correcting his own figures, as the costs for the national school should have read “£65 excluding £5 1s. 8d. for the Night School”. Immediately below the correction was printed the return salvo from a British School supporter, who signed themselves as “A Subscriber to both Parochial Schools” (Mrs. Grimshawe?). The correspondent extolled the successes of the British School system, “however despised and rejected it had been by some at the outset”. They thought that if a rector was upset by the Government decision to take education out of the hands of the National system, it was hardly a surprise. “If Mr. Gem desires to shut his eyes to the impressive phase Elementary Education has now assumed, and the necessity allowed on all hands of its speedy settlement of a broad popular and really national basis, there can be no hopes on enlightening him. The people of Aspley are, I believe, too well informed to be scared by any conjured vison of school rates, which, borne equally by all, would fall heavily on none…”

The vicar was quick to respond. The Beds Times – 6th February 1872:

“Sir, I do not purpose to enter into any controversy on parochial education, and therefore only wish to state:

1st. That I purposely abstained from any observation on the British School because I consider that criticism of this kind should be avoided, as it is only likely to stir up strife. But I demur to this inference that all the “facts” alleged by your correspondent about the school is therefore “unassailable”.

2ndly, Mr. Foster’s intention was that the School Board should be established in places where the education proviso was deficient, not in parishes like Aspley, already amply supplied with schoolrooms, teachers and scholars.

“A Subscriber” desires a change in the Education Act. But it is clear that if a change in it is ever affected, it will not be in the direction wished for by “A Subscriber”. The Manchester Conference has gone over to the Education League, and has pledged itself to secular Education, pure and simple. This would bring with it the destruction of the British system by the resolutions of the Conference no Board school master is allowed, even out of school hours, to give any religious instructions. The lips of every English schoolmaster, accepting office under a School Board would be for ever sealed on those sacred subjects which, as Christians, he has hitherto regarded as the most important of all.

Further, I will only refer “A Subscriber”” to the admirable speech made at Sandwich last week by a member of the Government, Mr. Knatchbull-Hugessen.

Your obedient servant, S. Harvey Gem.

Battle lines thus drawn; the situation proceeded with each side trying to get the most favourable view of their school into the newspapers. The Beds Times of 2nd March 1872 featured reports on the “Day of National Thanksgiving” thrown for the recovery of the Prince of Wales (who became Edward VII) from typhoid. It said the village was decorated in red, white and blue with arches decorated with flowers thrown up across the roads. “The flag of England was hoisted on the British School, and at its entrance gate was another arch of laurels supported by two tricolour flags. Both representative – the one, that of the people – the other, that of Prussia suggestive of the wishes of the people of England on one of the leading questions of the day – education – “compulsory and un-denominational.” However that may be, the festal decorations of this pretty village were most picturesque, and the tout ensemble in admirable keeping with the occasion they were to celebrate. The whole of them were designed by Mrs. Grimshawe and carried out under her superintendence.” It was also Mrs. Grimshawe that read out The Queen’s Letter, giving an update of the Prince’s health, “with clear voice and intonation”. The children then sung a specially commissioned song, “God Bless the Prince of Wales”, comprising of four verses written by… Mrs. Grimshawe. It started:

“Throughout the homes of England

And all her distant land.

The voice of prayer ascended

For God’s Almighty hand

To save—to bless her people

And spare her Monarch’s Son,

At gate of death unconscious;

The people prayed as one.”

Not to be outdone, the very next article in the same newspaper edition had the news from the National school. To celebrate the Prince’s recovery, they had had a tea with cake for 140 children and the church choir, the award of prizes for writing, maps and needlework and then sung their own song, composed by Mrs. Wall, mistress of the Girls’ school.

“Now through the length of Britain’s isle,

High songs of praise shall ring,

To-day we welcome back our Prince,

Our future King.

It pleas’d our God to lay him low,

In sickness and in pain,

Yet He in mercy to our prayers

Healed him again.”

Stirring stuff indeed! The issue of costs was to be brought up time and time again. Who would be paying for the new school system if it were taken out of the hands of the church groups? The local rate payers didn’t think it should be them. In July 1872, the Beds Mercury published the official notice for the setting up a “School District of Aspley Guise” and therefore necessitating a School Board.

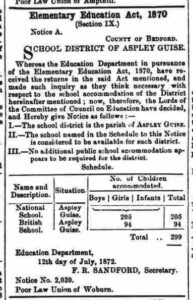

“Elementary Education Act, 1870 (Section IX.) Notice A. County of Bedford. School District of Aspley Guise. Whereas the Education Department in pursuance of the Elementary Education Act, 1870, have received the returns in the said Act mentioned, and made such inquiry as they think necessary with respect to the school accommodation of the District hereinafter mentioned; now, therefore, the Lords of the Committee of Council on Education have decided, and Hereby give notice as follows: –

I. – The school district is the Parish of Aspley Guise

II. – The school named in the schedule to this Notice is considered to be available for such district.

III. – No additional public school accommodation appears to be required for the district.

Schedule:

National School, no. of children: 205.

British School, no. of children: 94

Total: 299.

Education Department, 12th day of July, 1872. F. R. Sandford, secretary. Notice No.2,039. Poor Law Union of Woburn.”

…but nothing seems to have been done about it over the next six months. In the time since the jostling in the press had mentioned that each school had about 100 pupils and there were a 100 without any schooling, the National School seems to have leapt to 205 while the British had just 94. Was there some massaging of the figures?

In an attempt to settled which schools were where, how much they cost and how many pupils attended county-wide, an education survey was taken. The local results were published in the Beds Times in August 1872. This showed that the National school in Aspley had received grants of £273 10s. 0d. for buildings, enlargements and improvements for the 92 day and 18 evening scholars, plus an annual grant of £70 1s. 8d. The British school had not received any building grant at all, but had annual grants of £66 12s. for their 67 day and 78 evening scholars.

In September, the Grimshawe’s repeated their garden fete of the previous year at Aspley House for all the local school children, about 200 in number. There was a long list of local dignitaries in the Beds Mercury, including Her Grace the Duchess of Bedford, two other Russell ladies, Colonel’s, Major’s, M.P.’s and local clergy, although not Rev. Gem of Aspley Guise or the National school Master and his wife. Mrs. Grimshawe’s welcoming speech was shorter, but included the lines “I am sorry that the master of the National School is absent. Your rector’s absence too I must also regret, and I am sure you will all share that regret with me; but we must allow everyone to have freedom of thought and will to act as they conscientiously believe to be right and best, which we desire for ourselves…”

There are very few references to the British school in the National School log book, just a few notes on children having swopped schools to go there instead, but Mr Wall recorded in it “Joint treat given by Mrs Grimshawe to both schools. Over 30 of the National School children did not attend as their Master & Mistress were not invited.” This was followed by an entry reporting on the National School’s own treat that 138 children attended a week later.

A long letter appeared in the Beds Times on 28th September 1872, from a writer signed as “Tilbury” under a heading of “Women’s Rights” and how Mrs. Grimshawe had overstepped the mark with her comments about the National School master at the Fete. “This lady is entitled to great respect as benevolent and philanthropic person, an indefatigable admirer of Earl Russell, and evidently one who directs her thoughts to matters of serious and solemn import. It is evident also that she thinks the occasions on which she meets the combined schools’ children on the lawn of Aspley House are occasions of considerable importance, for she always addresses the children on horseback, carrying our thoughts and memories irresistibly back to Queen Elizabeth at Tilbury Fort.” The writer also disliked the “…sneers at the master of the National School and at the rector of the parish, regretting their absence… She has unfortunately exhibited that defect of judgment which is often the real defect of women when they interfere in the practical government and business of the world.” and continues, “Their judgment on abstract matters is better, surer, swifter than that of men. Their judgment on practical matters cannot be so good. Their domestic habits of life necessarily hinder them from that contact with the minds, habits, and of men, from that experience of men, their motives, vices, follies, weaknesses, without which it impossible to legislate wisely or safely for mankind.”! The letter ends “It is plain that there a great desire on the part of Mrs. Grimshawe to do good; but it certainly appears to me that she does not go the right way.”

The Beds Mercury of the same date, 28th September, had an entire column from Mrs. Grimshawe, headed by a copy of a petition she had received just before the fete:

“Aspley Guise. Village Fete at Aspley House. We have been requested to publish the following correspondence: –

“We, the undersigned, being members of the Committee of the Aspley Guise National School, desire hereby publicly to protest against the wrong inflicted on the children of the school by the exclusion of the Master and Mistress, Mr. and Mrs. Wall, from taking their proper place at the head of their scholars at the entertainment to be given at Aspley House tomorrow, – a proceeding calculated to lower them from the position they rightfully hold.

Harvey Gem, Rector,

S. Parker,

C. Blackden

W. Forester.

Sept 13, 1873. To Mrs. Grimshawe, Aspley House.”

Gentlemen, – ln reply to a communication from yourselves (the majority of the National School Committee), you must pardon saying I could not avoid smiling at so formal a protest on my refusal to invite this year to our village fete the National Schoolmaster. But the spirit of the inhabitants of Aspley is well known, the variety of their opinions, and the energy with which they one and all take up any question which they may interested. Yet I think we are, or ought to be, all agreed on one point, that variety of opinion may exist without variance, and mere difference of opinion ought to exist without personal differences.

Being much engaged, superintending the decorations for the fete, my impression on first reading it was that, having already stated our reasons for such exclusion to the Rector, such protest called for no further reply on my part. Yet second thoughts on a second reading may, perhaps, be best; and I cannot by silence give consent to the tone of feeling and doubt that protest appears to me to contain.

You say, ‘Inflicting wrong on the children of the National School.’ ‘Lowering the school in the position it rightfully holds.’ Strange words, I think, to apply to anything I have either said or done! And I appeal from such private misinterpretation of my conduct to my public acts that are before you. Through the Press they were widely known last year, and to the public I must look for a morn faithful interpretation and more favourable judgment, if not from those who ought to know me better. I repudiate such misconception of conduct on your part, and I conceive that had you taken a little more time for consideration, you would not have so worded any remonstrance a difference of opinion might have led you to make the occasion.

You arouse me to speak, and though without the slightest annoyance at the course you thought right to adopt: yet it is with no slight feeling of emotion that I should have been so misunderstood that I commence my reply. For such purpose I must go back to last year. The question of National Education had been agitating all minds interested in the subject. The new Elementary Education Act had come into operation, and I at once, with Mr. Grimshawe’s approval, seized the opportunity it gave me of carrying out a long cherished project – that of endeavouring (so far as a humble individual like myself could do so) to destroy the detrimental rivalry that had so long existed between the two parish schools of this village, dividing, I may say in round numbers, the elementary education of the place. With such object in view, I naturally sought all the co-operation I could, and without which I could have done nothing. The mental and personal exertion it cost at the same time to organise such a gathering as I proposed – on Liberal principles, and Christian principles of charity, you will see, must have required considerable efforts on my part, and I spared none. I took up the matter with a woman’s enthusiasm; and if such course, as it appears, has drawn to myself the disapprobation of some, yet, though it does not appear here, I have received the high approval of others, to which I cannot allude without sincerely thanking them for their generous support. Powerless woman may be able to carry out any purpose of her mind, such support gives a spirit to proceed, that, I trust, no want of moral courage woman’s part will ever cause to fail. To return now to last year. On such principles, with such object, and with such hope, Mr. Grimshawe and myself gave a village fete to both British and National Schools. I hope exception may not be taken to such verbal precedence on my part. You are aware that, in recognition by Government, and under the now Education Act, both schools are equal, and, in speaking, I adopt an alphabetical as well as chronological arrangement, – the chronological order being that the British School was established here many years before that of the National, as also the British School Society preceded by several years the establishment of the National Society. Until the rise of this latter, the British Society was the only society for the education of the poor. Its grand principles of a Bible education and unsectarian teaching gradually drew to it the patronage of most of the leading men and thinking minds of that day, as of this; and Mr. Gladstone has declared it the model for a really national education. Among its supporters of the generation in which it arose was the then Duke of Bedford, who received Lancaster as an honoured guest at Woburn Abbey, and established the British Schools at Woburn. Since then the successive Dukes of Bedford have ever given a powerful and influential support to the British School Society. Earl Russell takes a most active part in promoting its interests. I need not say with which society my sympathies are: they are known, and at the time my impartiality regarding both schools here I thought was too well known for you to address me in the terms you have. Everyone must have their preferences. These do not involve prejudices, and we must all advance what think right with that charity without which all orthodoxy of doctrine and moral action in worthless.

While I was last year endeavouring in the most impartial manner to arrange such fete, the National Schoolmaster not only wrote me letter unbecoming his position, but behaved with great rudeness and discourtesy – ‘banged up’ his books when I was speaking to him, and, turning his back, walked off, saying would ‘have nothing to do with the fete,’ and ‘that he washed his bands of the affair.’ He consequently was not present, and his scholars enjoyed themselves without him. Is it surprising that this year I did not intend to extend my invitation to him? When the Rector asked me, I stated to him the only conditions on which I would so.

The National Schoolmaster, to say the least, set at nought and despised my invitation. The Rector will know where precedent might be found, to which I might here reference.

Though I could not invite the National Master, I did not see that on his account the National children were to be deprived of their promised fete together with those of the British School. I, therefore, chose a holiday, and fixed Saturday, when they would be free and liberty to attend. The first year of our fete occurred the conduct I refer to. The second year I was obliged to mark my sense of it. It is now past and gone. For the coming year: this may now be a fitting opportunity to announce to you that I purpose next year giving an invitation again to the National Master and Mistress, as well the National children, together with the British. Ending this long letter, I cannot more distinctly assure you, gentlemen, of the misconception I consider has dictated your communication than repeating words you may have heard before. ‘There are two parish schools in this village. Both acknowledged by the Government of our country. Each, I hope, their mission of usefulness. The one poor – by some despised and rejected. The other rich – by many patronised and supported. To both as a Christian I must wish success.’ “

Yours faithfully, E. M. P. Grimshawe. Aspley, 17 Sept.”

How had the National school dealt with this furore internally? They held their own day of celebration. The children must have been getting tired of the marching and singing! This appears directly below Mrs. Grimshawe’s letter, as above, in the Beds Mercury:

“NATIONAL SCHOOL FESTIVAL. On Friday, the 20th inst., the annual festival the Aspley Guise National School was held. The children, headed their teachers, marched in procession to the Church, where a short service consecrated the rejoicings of the day. A substantial tea, provided Mr. Lilley, of Woburn, followed, – the National School-rooms being decorated for the occasion with many festive devices, among which was a very effective one of gold letters on scarlet ground framing the inscription “Long live our noble Duke and Duchess.” At five o’clock, her Grace the Duchess of Bedford entered the school-rooms, and took her seat at the head of the long table on which the prizes to be distributed were arranged. The Rector then addressed a few words to the supporters of the school, informing them of its continued progress in efficiency. A larger Government grant had been obtained than on any previous occasion, and the exertions of the master and mistress, Mr. and Mrs. Wall, had enabled 29 children to pass in the “extra subjects” of geography and physical geography. The prizes for good attendance were now to given away, and the Rector desired to express to her Grace the sincere acknowledgments of all present for her great kindness in coming among them that day, and their earnest wishes that the Duke and herself might long enjoy the honours of their high position. Each child then came forward to receive from her Grace’s hand the toward it had earned, a favour which the little ones will no doubt long remember.”

Another specially-written song followed. But these were not the only pieces in this edition of the Mercury that week. On the letters page was a long reply on the matter from the Rector himself.

“The Village Fete at Aspley House. To the Editor of the Bedfordshire Mercury,

Sir, – The able and interesting letter of Mrs. Grimshawe in your columns calls for a few words of explanation from me, after which I have no intention of trespassing further your space. On reading the exposition of Mrs. Grimshawe’s views about the British and National School, your liberal readers will naturally exclaim – Bigoted Churchmen! enthusiastic lady, nobly vindicating the cause of the oppressed, and the principles of true Christian charity! But let me invite attention to the humbler region of village facts. Is it the case that the British School was “despised and rejected” Before Mrs. Grimshawe moved at all in these matters, I had established a working-men’s reading-room in the house of the British Schoolmaster (of which kindly offered me the use on account of its central situation), and this I carried on for two whole winters with success – becoming thereby as well acquainted with the British Schoolmaster as I was with my own valued master. Moreover, when invited so to do, I attended the entertainments given in the British School, and I expressed on those occasions my pleasure in coming there, to recognize our common ties of Christian brotherhood, and the ample field which there was, in my opinion, for the work of both schools in this parish. On one of those evenings I examined the children in religious knowledge, at the request of master, in the presence of the parents and supporters of the school. Soon after Mrs. Grimshawe threw herself into the educational interests of the place, I gave her the use of the National School on one occasion for an exhibition by the British Schoolmaster. At this very time, as now, several of our leading gentry, as well as the tradespeople, subscribed both to the National and to the British School. At that period “detrimental rivalry” of which Mrs. Grimshawe complains existed almost entirely in her own imagination: at any rate, the clergyman of the parish was doing his best to render it only an honourable emulation in work and duty between the two schools; but, at this moment, the project of a combined school-treat (excellent in itself) was so carried out in detail as to be far from impartial affair. It was on this ground, and not at all a matter of principle, that we objected to its management both this year and last. The letter of which Mrs. Grimshawe complains had the approval, before Mr. Wall sent it, of a member our committee. But apart from the personal question between Mrs. Grimshawe and Mr. Wall, there was condition annexed by her to his admission to the festival this year, which I could not consent to fulfil. The National School was to be given up for entertainments alternately with the British. At first sight, nothing seems more reasonable, but there were grave objections to the plan. We have a night-school three evenings a week, and this would render the arrangement of the school-room for entertainments highly inconvenient. The British School is central, and lighted by the village gas, an advantage which ours cannot have; and, when one school-room is so well adapted and readily available, I see not why a second should be required for the same purpose. With those particulars, however, I must not trouble you further: my only wish is show that it is on details, not on principles, that we have differed with Mrs. Grimshawe. I am very happy to find, however, that it is her purpose to invite our master and mistress next year, which is all we wished for on the present occasion. To mark our regret at their exclusion, all the resident gentry of Aspley absented themselves from the Aspley House entertainment (with the exception three individuals), and 30 of the children, of their own spontaneous feeling, gave up the pleasure of the treat, rather than go where their teachers were not welcomed.

Your obedient servant, S. Harvey Gem. Aspley Rectory, September 24, 1872.”

Given that the entire newspaper was only eight pages long at that time, the coverage of this village spat accounted for a significant part of it! You may have thought each side would have retired and called it a draw. But it appears someone (Mr. Wall?) was not satisfied that his character had been suitably cleared. Rev. Gem had to write again, to the 12th October Beds Mercury:

“Aspley Guise Schools. To the Editor of the “Bedfordshire Mercury.”

Sir, – I have again to ask your indulgence. My letter on this subject, written under heavy pressure of duties which have the first claim upon me, has been thought insufficient; it is complained that I have not gone through the whole facts. Now, to enter into the details of differences that happened a year ago, – and which should by this time be forgiven, if not forgotten, by all concerned, – is most repugnant to my feelings, and I decline the task. But, explanation on one point, and as an act of justice to Mr. Wall, it may be right to say that his supposed personal insult to Mrs. Grimshawe was recently examined into by three gentlemen of the committee and myself, and was found to deserve no such name; it appeared that what occurred was in fact trivial, and that Mr. Wall had received much provocation. This latter fact I more especially know from an investigation I made into it in the presence of Mr. Palmer, the British schoolmaster.

Then as to Mr. Wall’s “impertinent letter,” I have now before me a letter written September 6th, 1871, by Rev. W. D. Isaac, the clergyman officiating in my absence, who knew the cause of provocation and all the circumstances, in which he says, – “I do not think Wall was fairly treated by Mrs. Grimshawe, and to the letter he wrote to her, which she calls impertinent, I am rather disposed to consider it under the circumstances that called it forth a proper one.”

The facts of the present year are these, – and they of themselves furnish ample justification to the committee and other friends of the school. After a long season of quiet, during Mrs. Grimshawe’s absence, that lady sent out “at home” cards for a specified day without any indication to me, the committee, or others invited, of a school treat being her object, and the invitations were accepted in ignorance of it, and of her intention to ask the National School children without their master. As such a proceeding was calculated to lower the teacher the eyes of the school, to injure his authority and discipline, and to excite dissension in the parish, I called on Mrs. Grimshawe and remonstrated, but in vain. Finding her inexorable I told her I could not sanction her highly objectionable proceeding by my presence at her fete, and should not attend. The school committee took the same view, and thought the case sufficiently serious to make a formal protest against Mrs. Grimshawe’s intentions; but still she persisted. She was willing to yield on two conditions, one being impossible for reasons given in my former letter, the other equally so, namely, an apology from Mr. Wall, without (of course) any admission of the provocation given to him. I forbear to add more detail, as I might well do, to this mere outline of the recent facts. I have been all along willing to believe in Mrs. Grimshawe’s good intentions, although in common with the friends of our school I have found it difficult to reconcile her proceedings with her professed “good feeling for its welfare.” Assuming, however, that good feeling, one would have thought a little consideration would have shewn Mrs. Grimshawe that if she could not forgive the supposed affront she should have previously referred the matter to the committee, and not have brought the children into the question, by putting an open slight upon one to whom their respect was due. Mr. Wall might have been present under reservation; anything rather than endanger the interests of the school.

I would add only a personal remark. It is hard measure for clergyman to be called from his higher duties to enter into controversy with persons of leisure who may have relish for discussion and disputation as a mental distraction. We must be excused, I think, if in such case our letters are hastily written, or curtly or imperfectly worded.

Your obedient servant, Aspley Rectory. S. Harvey Gem.”

Mrs. Grimshawe did not write to defend herself; this was done by Mr Palmer, British school Master, the next week. Preceding it was a notice that all six local children entered had succeeded in a science exam at South Kensington Art Department, thanks to the teaching by Mr. Palmer, “quite distinct from his British school”. Many villagers came to the certificate ceremony, taking an “astonished interest” in the various science experiments shown.

“Aspley Guise Schools. To the Editor the “Bedfordshire Mercury.”

Sir, – I have hitherto been a silent, though interested reader of the letters in your paper in reference to our village school doings, and should have remained silent, but for another letter from the Rev. S. H. Gem, in your last issue, where my name occurs in such a way that it requires an answer, or I might be justly accused of double dealing.

I am surprised at Mr. Gem’s inconsistency, which is unaccountable, desiring to live in harmony and peace, to “let by-gones be by-gones,” “the past be forgiven, if not forgotten, by all parties,” and yet, in spite of these professions, he is not satisfied with writing once, but seeks by misstatement to deal a heavier blow in a second letter, declining to enter into details of the past, and yet dealing with one-sided details to the end of his letter.

I thoroughly believe that had each of the gentlemen who inquired into the alleged provocation to Mr. Wall been made acquainted with the facts of the case, they would have come to the conclusion that it was “trivial” indeed. In fact, I most emphatically deny that Mr. Wall had any cause for provocation; this is just what Mr. Gem wished me to admit when he made the investigation he alluded to in my presence: but my reply to him was “No, sir, I admit nothing of the kind.” Mr. Gem may still hold his opinion, and perhaps induce others to see with him, but let him act at least consistently by stating both sides of the question, then I think that every unprejudiced mind would say that I, the British Schoolmaster, had the most cause to feel aggrieved. Let Mr. Gem do any act of justice to Mr. Wall, by all means, but let him be just also to Mr. Palmer at the same time. Mr. Gem declines to show the imagined cause of provocation; and why? because it is so “repugnant to his feelings.” Then why write at all? But I know it all from beginning to end; and were it not so strictly local, and uninteresting to general readers, I would state it without fear of contradiction, and the public verdict would, I sure, be that it was puerile and bigoted in the extreme; in fact, there was nothing said or done to hurt Mr. Wall’s feelings in any way. The truth is, Mrs. Grimshaw acted in good faith throughout. With the intention of making the schools work agreeably together, she felt they required to be placed upon an equal footing, as viewed by Government, and that neither the British or National should take precedence one of the other, but that the children of the two should intermingle. She also arranged that the master of one school with the mistress of another should preside at one table, and the same arrangement should be observed at the other. This intention is unknown to most people, and it is ignored by Mr. Gem.

Mr. Gem considers there was no insult from Mr Wall to Mrs. Grimshaw. Now much depends upon the medium through which we an object or action, and as much depends upon the manner as the words to which utterance is given, I venture to say that if I, the British schoolmaster, had conducted myself with such impropriety of manner and words to anybody connected with the three gentlemen of the National School Committee who enquired into the matter, as Mr. Wall did to Mrs. Grimshaw, they would have come to an opposite conclusion to that they arrived at; and had I acted so, when my passion was cooled I should have thought myself most unmanly if I had not offered an apology even before I was asked. Let me say word or two on the “impertinent” letter from Mr. Wall to Mrs. Grimshaw; if the right word had been used it would have been libellous letter, written with the evident intention of damaging my own reputation in that lady’s estimation, accusing me of the meanest tricks – of “untruthfulness”, ”want of truth and honesty,” and gross misrepresentation (I quote from the letter). Mrs. Grimshawe asked me to explain the letter in Mr. Wall’s presence, when I affirmed what I do again reiterate – that it is tissue of untruths. It was in attempting to defend his charges that he certainly lost his temper, and hence Mrs. Grimshaw’s words – that he “banged up his books and said he should not attend, and that he washed his hands of the whole affair.” But there was another witness on the occasion, but his testimony is by Mr. Gem not alluded to, although similar to my own. In self defence I appealed to Mr. Gem, who proposed meeting at the Rectory, where mutual explanations would perhaps heal the breach. Here Mr. Wall would have had the opportunity of establishing his charges to my shame, or I the pleasure of refuting them. I say nothing of that interview now farther than this – by mutual consent the past was to be forgotten. How far this has been carried out let Mr. Gem’s letters answer; and I will add, should the gentlemen of the National School Committee, who know me well enough, think the charges in that letter to be true in any way, and consequently look on me as bearing such brand, I challenge publicity, and propose that the managers of both schools form a committee and enquire impartially into the matter, and not as Mr. Gem has done, investigate one side of the question and ignore the other. Such an enquiry would show clearly enough whether any cause existed for Mr. Wall’s so called provocation, and would give that gentleman the chance of proving what he asserts of me to be true, and if so, the right to tear away the mask that must have worn for twelve years as British schoolmaster in Aspley, retaining the testimony of my neighbours to my character for uprightness and integrity which I have not deserved.

I need say nothing in defence of Mrs. Grimshaw’s acts of this year, she is well capable of defending herself without any champion; but let it be known her intention – perfect equality of the two schools – was carried out, the children being intermingled to destroy differences and distinctions, and the treat was given on a Saturday, which is not a school day, and when the children would be free to attend. In conclusion, I am sorry to appear in print in this affair; but silence would be a tacit admission of wrong doing on my part, which I must repudiate.

I am, sir, your obedient servant, J. Palmer. Aspley Guise.”

Did that silence the comments and allow the situation to heal? Well… no. If only someone had a blow-by-blow account of the conversation that had taken place in 1871 that had seemed to so upset so many people. Thankfully, they did. The vicar wrote again on the 26th October with just that account, direct from Mr. Wall. You can almost see the steam rising off his words…

“Aspley Guise Schools. To the Editor of the “Bedfordshire Mercury.” Sir, – My last letter was reluctantly forced from me by representations, from various quarters, of the necessity of justifying the committee, the friends, and the master of the schools, in relation to Mrs. Grimshawe, which it was urged I had not done in my former letter; – my present one by Mr. Palmer’s letter; which obliges me to publish the earlier facts of the case. These I had held back out of forbearance for Mrs. Grimshawe as a lady, and in the interests of peace. They will be found in the subjoined statement, drawn up with my approval by Mr, Wall, who made notes at the time, and which, our conciliatory attitude being mistaken, I now make public, expressing at the same time my deliberate opinion that Mr. Wall has been greatly injured, and is undeserving of any blame.

I have by me an exact copy of Mr. Wall’s list of scholars, with 28 of their names as erased by Mrs. Grimshawe herself. The conversation at the British School was lately read in the presence of the witness to whom Mr. Palmer alludes, namely, Mr. Pickering, who suggested no difference except in the single sentence noted as doubtful.

To Mr. Palmer’s unbecoming and (to avoid a harsher term) unscrupulous letter I do not condescend to reply; but I will observe that at the investigation before which he misrepresents, I greatly blamed him for accepting at Mrs. Grimshawe’s hands the name of evening scholars to whom he had no right whatever.

Your obedient servant, Harvey Gem. Aspley Guise Rectory, Oct. 17, 1872.

FACTS IN CONNECTION WITH MRS. GRIMSHAWE’S FETE WITH REGARD THE NATIONAL SCHOOL, 1871. Mrs. Grimshawe called on me and asked me to make her out, from my registers, a list of day, Sunday, and night scholars. She told me she intended giving a tea to the children of both schools, their parents, and committees. I made out a list, giving the names of the children, their ages, and the names and residences of their parents. I was careful to have everything correct, and in compliance with Mrs. Grimshawe’s expressed wishes I took the list to Aspley House.

The next day, on meeting Mrs. Grimshawe, she told me “she had scratched a number of the names off my list as they belonged to the British School,” reducing my list from 137 to 109. Mrs. Wall went the next morning to ask to see the list. Mrs. Grimshawe told her, after reading the names of those scratched off, that the British School could not muster so many children, therefore she had cut off number of the national scholars, and that several of them were to go to tea with the British School as scholars of that school. Mrs. Wall asked her if it would be fair and just to the National School to take a number of its scholars and make them appear as scholars of the British School. Mrs. Grimshawe replied, “It is not for you or for any one to question me about my fairness to the National School.” Mrs. Wall replied she was afraid it would be unjust to the Rector, the school committee, and supporters who were present at the fete. Mrs. Grimshawe said, “I shall please myself. I have a perfect right to do as I think proper; neither Mr. Gem nor Mr. Wall have anything to with its being fair or not. Those children have promised Mr. Palmer to go to his night school next winter if he commences one, and I have determined that they shall go to my tea only as British night scholars.”

Mrs. Wall asked to allowed to bring back the list to me. On her return I went to each scholar’s parent (marked B. N. S. in the list) and asked if they had promised that their children should attend a British night school if one were opened, and they preferred them to appear as British scholars at the coming tea party, and each and all denied having made any such promise. Then I wrote a letter to Mrs. Grimshawe, explaining the case as it stood, and the bad effect it would have upon my school, and asking for justice to the school and children. Having submitted it to the approval of C. S. Parker, Esq. (a member of our committee), and the Rev. W. D. Isaac (officiating clergyman), I sent it to Mrs. Grimshawe. Shortly after I received a verbal message in reply to my letter – “You are to go down to Mr. Palmer’s directly and meet Mrs. Grimshawe there.” After a little hesitation I went, taking with me my registers. I found Mrs. Grimshawe on horseback in the playground of the British School, Mr. Palmer with my letter, and Mr. Pickering standing by. The following conversation took place:

Mrs. Grimshawe: Mr. Wall, I’ve given your letter to Mr. Painter.

Mr. Wall: Very well, ma’am; I believe will find what I have stated correct.

Mr. Pickering: I think it a very wrong letter, altogether. [Mr. Pickering was then ignorant of the provocation given. – S. H. G.]

Mr. Wall to Mr. Palmer: I’ve brought my registers, Mr. Palmer, to prove that those children are on my books, and in actual attendance at my school.

Mr. Palmer: They have promised to come to my night school.