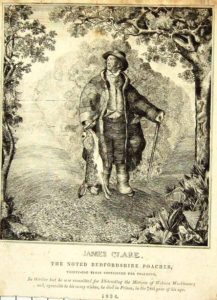

James Clare

A print exists of an engraving of a country poacher out on an expedition at Woburn. It shows a stocky man, in a long patchwork coat, holding a hare in one hand and stick in the other. It looks very much like there is also something feathered sticking out from his coat pocket! The Bedfordshire Archives and Records Service has a copy of it under Z49/365.

The label below it reads:

“James Clare. The Noted Bedfordshire Poacher. Thirty-one times imprisoned for poaching. In October last he was committed for ill-treating the mistress of Woburn Workhouse; and, agreeable to his many wishes, he died in Prison, in his 78th year of his age. 1834.”

Did James Clare actually exist? Who was he, and did he really commit so many crimes?

There have been Clare’s in Woburn since at least 1585 when Venus Clare was married there. Fitting this time frame, there was a baptism of a James Clare in Woburn 30th May 1762, and then a marriage of a James Clare to a Mary Cook in Woburn in 1785. They had two children, William in 1789 and Martha in 1792, but Mary died in 1799. Perhaps it was his efforts to provide for his family that led Clare to steal game that was not his. Stories about his poaching life only started appearing in the local press once his exploits rose above the normal poacher’s prison tally.

The Victorian Crime & Punishment website index has 15 entries for him, yet there seem to have been many more, judging by the sensationalist press reports about him. His brief description in the first entry of 1803 tell us: “Height: 5ft 5in., Hair colour: Brown, Complexion: Dark”, but his complexion in later committal details varies to “pale”. His age also seems to fluctuate a little, but it would probably have been the best guess of the prison authorities at the time.

8th November 1803 – Snareing [sic] – 3 Months – Aged 44.

6th December 1813 – Snareing [sic] – 3 Months – 55.

17th December 1818 – Game Laws – 3 Months – 48.

17th November 1819 – Game Laws – 4 Months – 49.

2nd October 1820 – Breach of the Game Laws – 4 Months – 64 – “A cripple. Widower”.

12th April 1822 – Breach of the Game Laws – 3 Months – “Occupation category: Needlework”.

23rd May 1823 – Breach of the Game Laws – 3 Months.

24th October 1823 – Breach of the Game Laws – 4 Months.

26th October 1824 – Breach of the Game Laws – 3 Months.

14th April 1825 – Breach of the Game Laws – 3 Months.

2nd September 1825 – Breach of the Game Laws – 3 Months.

3rd March 1826 – Breach of the Game Laws – 3 Months.

6th April 1827 – Breach of the Game Laws – 3 Months – “14th time within County”.

14th September 1827 – Breach of the Game Laws – 3 Months.

The note of it being his “14th time” in April 1827 must have been brought up in Court, as it also prompted the first press article that I can find about him. The Huntingdon, Bedford & Peterborough Gazette of 14th April wrote:

“New House of Correction – Commitments. – Jas. Clare of Woburn (14th time); and James Deverrex, of Campton, three months’ each; under the game laws.”

Clare’s continued imprisonments had obviously had no effect on him. For many, a trip to prison would have been a life-changing event. There was no rehabilitation scheme at that time and prison was harsh and brutal as a deterrent against repeat offences. Yet James seemed to take it all in his stride and the authorities were amazed to discover he actually didn’t really mind! When compared the life of an ordinary peasant of the period, he considered a cell a better prospect than the living conditions in his cottage. The next article appeared when Clare was sentenced to three months for the 16th time, and this gave the Editor of the Huntingdon, Bedford & Peterborough Gazette an excuse for an examination of where the Game Laws and the basic social care system were going wrong. Published on 22nd September, 1827, the article was picked up and run nationally:

“Pauperism and its effects. – James Clare is for the 16th time committed to our gaol under a breach of the game laws. So well did the constable know the disposition of tis old man, that for two hours he left him in the street before conducting him to prison; and while left to himself, on someone observing that he then had a favourable opportunity of making his escape; he said , he would rather go to gaol, where sufficient food would be allowed him, than return to his parish, where he must either pine away through want, or return to his former courses. – Great difficulties exist in many parishes as to the best method of employing their poor; at Ampthill last year they were one day employed in digging a large hole, and the next in filling it up; and this year men are sent each with a wheelbarrow and a sealed sack containing a bushel of sand, and return with two bushels of coals; a journey of 16 miles with a full load they complain of as too laborious or a day’s work, and some of them have their eye on a gentleman’s preserves, and it is thought probable that they will return to their old pursuits of poaching; to them a prison has lost its horrors, they have been repeatedly confined there; and even transportation is thought to be preferable to the degradation of wheeling sand and coals, and receiving the sneers of all they meet with into the bargain. In the year 1807, only 2 poachers were committed to gaol, but in 1827, 95 were sent there for that offence only; not a presumptive proof this, that a prison produced a general reform, but on the contrary it is to be feared that what they learn from each other while confined in these schools, as they call them, after their liberation the farmer’s poultry, &c. and the grazier’s sheep, become objects of plunder. Already is game hawked about; and while opulent tradesmen and others who are not qualified or disposed to follow the sports of the field, will have their tables furnished with game, the salesman having large demands will give remunerating prices and, indeed, so completely has game become an article of traffic, that those employed in their delivery, without looking at the direction, conclude generally that the larger parcels and intended for sale. It is our decided opinion, that some alterations must be made in our game laws, as from their demoralising effects on the lower classes in society, pauperism rapidly increases, our gaols are filled to excess , our country rates to support them are intolerable, and to provide for their familied, parishes are most heavily burdened.”

The Huntingdon, Bedford & Peterborough Gazette again, 9th February, 1828:

“Commitments to the New House of Correction – James Clare, of Woburn, for the seventeenth offence against the game laws – three months.”

The Globe (who apparently had picked it up from the Bucks Gazette) commented on his habit of arranging his prison stays for the winter months on 3rd January 1829:

“Bedford gaol and penitentiary are very full; and the are now upwards of 40 prisoners confined under the game laws. There is one from Woburn (Clare) who has taken up his usual winter quarters for the twenty-first time. The offence of being found armed at night with intent to destroy game, &c. is punishable with transportation for seven years; but this sentence is seldom, if ever, carried into effect.”

The Huntingdon, Bedford & Peterborough Gazette yet again, 18th June, 1831:

“EFFICIENCY OF THE GAME LAWS!!! – On Thursday last, James Clare of Woburn was discharged from the Penitentiary in this town, where he had been incarcerated three months (being the twenty-eighth time) for destroying wild animals. To this feeble old man the prison allowances are comforts, when compared with the miserable existence he pines under when at his parish; and, according to his own expression, “a little exercise is all very well, after which he gladly returns to his town house,” meaning the prison, which to him has lost all terrors. Surely the great expense gentlemen are put to in preserving public nuisances and the serious expense incurred, both in individual parishes, and to the country at large, require that great amendments should be made in our abominable Game Laws.”

Clare was now in his 70’s. His last offence was very different for the former ones. He attacked Elizabeth Clevely, mistress of the Woburn Workhouse where he was then an inmate, with a clasp-knife. This occurred in nos.19-20 Bedford Street which was used as a workhouse for over 100 years before the purpose-built larger institution at London End, Woburn. The Northants Mercury said he was between 78-80 years of age. The relevant Quarter Session Records [QSR1833/4/5/7] are now available at Bedfordshire Archives & Records Service, who have helpfully provided on their catalogue a transcription of the evidence given, and therefore a detailed description of the event, as used in court can be given:

Elizabeth Clevely: James Clare was an inmate of the workhouse and between 12 and 1 o’clock all the inmates of the workhouse were at dinner. James Clare had some of the meal, pudding and potatoes and he asked for some more, which she gave to him. He then called her “a good for nothing bitch” and said it was not enough. She told him to eat that and then he should have some more and he called her a bitch and a whore and abused her with words and said that Mr Heighington, the overseer, had said he was to have as much as he pleased at any time. She replied he was to have as much as he pleased when the rest were at meals. Clare then said “you are a liar and a whore”. She took hold of his hair and said he deserved to have it wrung off his head. He struck at her with a knife which he had in his hand and which he used to carry in his pocket. It was as sharp as a razor. The prisoner cut her hand both above and below the wrist very deeply. He struck her with a great deal of violence. In the near moment he took the poker and brandished it and said he’d thrust it down her throat. Her hand was bleeding very much and she got away. The wounds were sewn up by Mr Parker’s apprentice. James Clare had often threatened her life. On the previous Wednesday he had told her he would ‘do her’ if he possibly could. A fortnight or 3 weeks previous he had held a knife at her saying “I’ll stab you to the heart, I would not mind stabbing you more than a beast”.

Robert Fowler, an inmate of the workhouse also gave evidence. He was present at dinner when James Clare called Mrs Clevely a lying bitch and many other names. He saw Mrs Clevely take hold of Clare’s hair and he heard her say something to him. Clare took hold of a poker and threatened her. He did not see Clare strike at her with his knife but he did see the knife in Clare’s hand. He saw Clevely bleeding very much.

The local doctor, Thomas Parker said that he had examined the wounds on Mrs Clevely’s wrist and arm and the cut on the wrist was slight. The other wound was of considerable extent and depth and extended across half of her arm. The back part of the arm was completely divided. The wound was inflicted with determined violence. It could not have been accidental. It would not have been inflicted by her running against a knife in the hands of another person. If the wound had gone a little deeper it would have deprived her of the use of her arm forever. As it was Mrs Clevely would not have use of the arm for some weeks, even if it goes favourably. He considered it a formidable wound. He heard the statement of Clare and he was of the decided opinion that it was not the case that Mrs Clevely ran her hand against the knife. The wound could not have been inflicted in such a way. He was convinced extreme violence and determination must have been used to inflict the wound.

Clare’s own defence statement was short. He said he did not cut Mrs Clevely’s hand. She ran it against his knife and she had been pulling at his hair. She had abused him before.

With the evidence being quite overwhelming, Clare was sentenced on 6th September 1833 to six months prison for “Cutting and Maiming”. His age was given as 81. Most of the newspaper reports of this crime agreed that this “notorious poacher” had had more than 30 convictions, mostly in Bedfordshire, but also a couple in Bucks.

His committal led to another story about him appearing in newspapers up and down the country, after being printed in the Bucks Gazette. At one of his poaching trials he had used a comical defence in court. This from The Globe of 7th November 1833:

“A curious anecdote is told of old James Clare, the Woburn poacher. Some years ago, when about to be committed, he was remonstrated with by a noble duke on the life he was then leading, and cautioned against destroying any more of his Grace’s hares. Old James scratched his head, and with well-feigned humility said, “I am sure I never killed any but my own hares, and should scorn doing so.” “Pray what hares have you got?” was the interrogative. “Why” said the veteran poacher, “mine are all marked, they wear brass collars, your Graces hare’s do not, and I can safely declare I never killed one that did not have one of my collars on.” – (the poacher’s snare) The old man’s ingenious remark drew forth a hearty laugh, and afterwards obtained for him the promise of a small annuity, provided he would take some other course of life. But the promise was useless, as he now declares, in his 82d year of his age, that he will preserve in poaching on the Duke of Bedford’s preserves as long as he is able to set a snare.”

But Clare did not live to trouble the free-ranging game on the Duke’s estate again. During his six-month sentence for wounding, he died in prison. The Bucks Gazette, 7th December 1833:

“DEATH OF JAMES CLARE. – On Sunday afternoon, James Clare, the Woburn poacher, terminated this life in the county gaol of Bedford. He died from pure old age, and is said to have completed his 80th year. From youth upwards he lived a life of a poacher, and always made it his boast that he could live without work. Though a pillage of game, particularly that on the Duke of Bedford’s preserves, he always maintained a high character for honesty, and notwithstanding the most tempting offers made to him upon condition of him discovering the parties to whom he sold the game, he never abused the confidence reposed in him. He had nearly completed three apprenticeships in gaol, having been committed 33 times, consequently the prison became his home or “town house” as he familiarly designated it. He had a great aversion to dying in the workhouse at Woburn, and to that is attributed the attempt he made to stab the mistress of it, in order to procure his committal to prison. In his youth he was a remarkably strong man; and at one time he could clear at a leap the highest fence* around the park at Woburn.”

(*This is unlikely to be the famous Woburn estate wall. That was constructed 1792-98. Other fencing must have been in place when Clare was a young man.)

The Northampton Mercury added a few days later that an inquest had been held at the prison by Mr E. Eagles, junior Coroner for Bedfordshire, “on view of the body of one of the inmates, by the name of James Clare, better known as the “Woburn Poacher.” The deceased, from the testimony of the surgeon who attended him, died from the effects of weakness, arising from extreme old age”, and a verdict of “Died by visitation of God” was recorded. He was buried at St. Paul’s in Bedford.

Some locally carried his name into folklore. One William Capp was committed to prison for three months in December 1849, for snaring game at Woburn. The prison officials duly recorded his identifying marks, which included: “Faint mark on the right arm of J. CLARE and 2 hairs [sic] in Indian ink”!

In September 1920, the Beds Times ran a story about the art collection of their then owner Mr Charles Edward Timaeus, which decorated the walls of the Beds Times offices. One of them was of James Clare.

“Among the pictures of special interest is a portrait in oils of James Clare, better known as “Bony Clare” a famous poacher at Woburn early in the last century. Stevens, the artist, has depicted him standing in a riding in the Woburn evergreens with 2 hares in his hand, and a worried look on his face, which is explained by the fact that the keeper is on his track. It is early morning and a beautiful light from the rising sun breaks into the alley between the foliage, and the whole picture is extremely well executed. There is an engraving of the portrait dated 1834… It has been observed that poachers and gamekeepers live to a good age. Evidently their vocations are healthy.”

That reference to “Bony” Clare is odd; it is not used in any other article about him.

It was another 30 years before Clare was mentioned again, which also occurred in the Beds Times. By now, the oil painting that had hung in their own offices was not known about. Columnist “Touchstone” had bought a copy of the print, and after discussing the contents of the picture, asked if any readers knew more?

Mr. H. Sylvester Stannard of Flitwick wrote in a week later with information:

“In 1877 I remember well that I was taken into a little room in Woburn by my father, who watched an old portrait painter at work in water colours. His name was I. Stratfold and perhaps the chief reason for my clear recollection of him was because he constantly sucked his paint brush. He was then about eighty years of age, and I was seven.”

So it appears the painting had possibly been produced much later from the contemporaneous engraving. Robert Stratfold was born 1797 in Woburn and would therefore have known Clare. By the time of the 1881 census, he was 83 and a widower and boarder in a house in Linslade. He was described as a retired general merchant and artist painter. He died in Bedford in 1886 at the age of 89.

I have not been able to track down where the original painting is now, nor an original copy of the engraving. The image of the engraving here was found on Google. I poached it. It seemed appropriate….