Mr Andy Buxton has suppIied me with his fathers early memories of Woburn Sands, and I am grateful to him for giving me permission to republish it here. I have illustrated his story with postcards from my collection.

“My birthday was on December 30th, the year 1922, according to a certificate of birth. I do not recollect the incident itself, but my father was Henry Buxton of Wavendon, my mother Edith Lloyd of New Bradwell. Edith was Henry’s second wife, the family broken by World War 1. An early son died in the war, in the Middle East. He had married but his wife died in the influenza epidemic and Henry’s wife died that same way.

Henry was a school teacher, headmaster of Wavendon Endowed School where he had served many years. He took Edith as his second wife. She was much younger than himself. Three members of the new family were born in Wavendon, Sylvia, myself, and Joyce, then Henry reached retirement age and had to leave the School House, and relocate, moving to Woburn Sands at 47 Wood Street.

Of my early years at Wavendon I recall essentially nothing. I claim of one thing, of lying in a cradle in a room with a sloping ceiling at the School House. I was too young to remember any more.

It was after the birth of the third child, Joyce, we moved to Wood Street. Wood Street was not an improved road. It was paved and sidewalks were installed several years later. But a number of trades people were able to pass – on foot or with horse drawn carts.

There were two milk men. Mr Chester brought his milk cans to be poured into a jug. Mr Witmee came with a large can to measure from, which was ladled into jugs. Coal and coke were delivered from a horse drawn cart, taken by workmen with bags of fuel on their backs to deposit in the coal shed. A couple of tradesmen offered their fruit and vegetables for purchase.

Perhaps I should tell you the layout of our house. The home had previously been owned by a Mr Tyers, a builder. We shall call the front the south side, and east, west, and north follow. The south west first floor will lead to the drawing room, the window, a bow window of stone. Continuing to the north the ‘living room’ is adjacent, then to the north the kitchen. A further passage from the front door follows the other side of the drawing room and living room leading to the stairs to a second floor; the under side of the stairs was a pantry.

Completely separate from the home was a working room and garage, used from time to time. This area began at the south face of the home, running to the back of the living room and pantry. The room to the north of the living room was the kitchen, and continuing to the north was another room, which was proudly called ‘the next place’, and held an outside toilet. The coal shed was next to the north, then a building that had been a stable, but then housed a number of chickens.

The second floor formed bedrooms – a main bedroom and a second bedroom. Across from the main bedroom was a third bedroom over the ‘work place’, and at north east a bathroom. It was interesting for us young people that the bathroom had a toilet and bath but was never used by us for that function. It was more often a storage place. It is the location for a trap door to the roof. This roof space never had wooden flooring. It contained a large cistern, through which all our water supply went.

It was at home at 47 Wood Street where the two youngest, Isobel and Tom, were born. The domestic arrangements were about as follows. The kitchen was the utility room holding a range for cooking, oil burner for minor heating of food. In one corner was a copper for washing clothing, and a sink and drain.

All meals were taken in the living room, joining as needed the washer lady, Mrs Beetle, and sundry house workers, of whom Evelyn lasted the longest. Dinner was the mid-day meal, which seemed to follow on Sunday a roast (often in the case of beef, with a course of Yorkshire Pudding).

Cold meat with the roast on Monday, stew or leftover dishes like mince, or shepherd’s pie later in the week. Fish was normally served on Friday. The most popular dish was our father’s boiled fish, which formed fish cakes or a fish pie as Saturday ‘leftovers’. Breakfast was bacon and egg, or usual alternatives. For tea we had sliced bread with butter and jam. Cake or small cakes were often available. After school at Bedford, meals changed to school meals and a home meal after the train brought us home.

There was mention of chickens at the table and our mother was active in egg production. The flock of Leghorn (white) grew later to a second flock, Rhode Red. A further flock (Buff Orgestane?) was housed in a third hen house. Eggs became a saleable commodity and a source of some money. Mixed grain was delivered by the Wavendon bakers, the Meales, who now had a van. Wood Street was by this time paved. From time to time a cockerel or surplus bird graced the dinner platter.

I recollect quite a number of Woburn Sands residents. Dr Holmes lived on Theydon Avenue at Wood Street. A large orchard separated his property from ours. Continuing along the street on the east, the neighbours were the Henmans. Mr Henman worked for the Duke of Bedford. They had one child, Joan.

Next to them, Wilson, Mrs and adult daughter. The Dawborns, father and mother and several children. Last in that block of four I don’t remember. The next block of four began with the Edwards, son John and a younger girl, whose name I don’t remember.

Next was an old lady, Mrs or Miss we never knew which, Mrs/Miss Pinder. She lived alone and was probably affected by arthritis pain. At last she had to move out to a hospital or home for the old and sick. We were convinced that she was a witch.

Mercy Stone lived in one of the next four home blocks but which one I am unable to recall. She later married to become Mrs Pikesby. Further to the east there were two or three larger homes. In the last of the group was Mr Witney and the next portion was his working farm and dairy.

Further again lived the Parkins, father, wife, and husband. The Parkins were noted for owning a small Ford car, in which Joyce and I would be invited to see some of the famous houses in the district.

On the other side of Wood Street, starting with the junction with Theydon Avenue was the Roman Catholic Church, a modest building of wood. Next to it was the Presbytery. It had earlier housed the Moores, Mr and Mrs. Beyond was a grassed and weedy space on which a donkey grazed, owned by Mrs Tomlin. It was a building site later for the Michelmoor and Maile families.

This brings us to our garden, a piece of land right opposite to 47 Wood Street, and mainly dedicated to vegetables. Adjacent to the garden was another parcel of land used by Mr Hunt for his garden. The Hunts lived on Theydon with the rear of the garden land on Wood Street. Very much later, 25 or 30 years, the Hunt family had a new home built and there they then lived.

Moving along Wood Street, the next home was that of Tom Garrett and his wife, son, and daughter Priscilla. Their home was notable for the big cherry tree behind the house. Tom Garrett was one of the two postmen in Woburn Sands, and a cheery man he was.

Further to the east was the house of the other postman, Mr Walker. Each postman had a wife and a pretty daughter. I am reminded of blind Mr Stell (?) living in Wood Street.

School days started for me in 1926 as I joined Aspley Heath School at the first class, with teacher Mrs Boxford. The route was up Wood Street, then to the hill to the square, then a few yards along to the Infant’s School.

After the first grade we moved to Miss Goodhall. The grade took to the main school building with Mrs Neville and grade three. All classes were heated with open fireplaces, using coal as fuel.

‘Silent reading’ was my most enjoyable lesson. The teacher passed out little green books with stories. I was keen on one about smugglers.

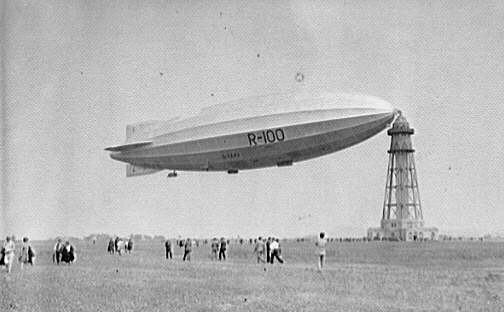

I must not forget the most excitement while at Aspley Heath School. Woburn Sands is quite close to Bedford and Cardington. At Cardington a group of airships was built, and the school was told of the launch of the R100, [1929] and all the scholars were assembled and marched, past the old oak tree, up on to the top of a hill, named Ling Hill. And there we waited for the release of the ship from the mooring it held there. In lovely sunshine finally the craft got away. Around noon the airship scouted the district. I well remember when the ship came close to the church. It was almost close enough to touch!

The R100 took a number of visits to the continent. It crashed and most of the crew and visitors perished. Later, a special train carrying their remains followed the line from Bletchley to Bedford. Most of our residents watched the train, decorated with a wreath, announcing its purpose. Reverently they moved on, and the people were destined to be buried in Cardington. [It was actually the R101 that crashed. The R100 was broken up for scrap in 1931]

Moving to cheerful matters – progressing, I applied for a scholarship and was given one. Thence to Bedford Modern School, I was placed in grade 1A1. I was dressed very differently from elementary school. I had a suit with long pants. Shirts with detached collars were worn; the collars were hard and starched, with two studs to connect to the shirt. Most evident were school caps, perched at the back of the head almost as a badge.

Regular evening work was assigned, usually for three subjects. The work needed the use of writing tablets. We were glad of the part of the day at which homework could be done. None was done on the train, at the St John’s station, and the Woburn Sands stop.

From the years of my early childhood until the war years, summer holidays were routine. Seaside for two weeks, a long train run and all the excitement anticipating would bring. There were important preparations to be made. First, the silver had to be boxed and put into safe hands at the bank. Second, a trunk had to be packed with necessary clothing for the holiday use. The trunk was taken to the railway station to be shipped to our destination. Then, near to our going away, big valises were packed, and repacked, to accompany us to the holiday.

For several years our holiday destination was Hastings. The Scriveners had known the family in Wavendon, and their home at Cornwallis Street was our centre.

We enjoyed side trips, but we children would rather be by the sea. One, a trip by paddle steamer, took us to Eastbourne. An expensive tea was enjoyed near the pier. I recall that a dish of shrimps was shared out. Surveying a clean plate I reported ‘My shrimps hadn’t got any heads or tails’.

On another trip by horse and wagon we were taken to see and smell the lavender fields. The men and kids had to disembark for some steep hills, while the lady passengers remained to be pushed and pulled up the next hill.

One holiday at Hastings was full with Normans replaying the Battle of Hastings. The Sunday holiday was dedicated to band music, and singing of community songs.

The Scriveners moved and our next holiday was a visit to Ramsgate. The shore was sandy, not marked by shingle as at Hastings. Dad spent a good deal of time at a mechanical cricket game, for it was Test Cricket time with Britain against the Australians. Bowling, hitting and running were all simulated in the game. We children were taken by small boats for hire on the water ways in the Ramsgate Park. Lots of fun but too expensive. Back to the seashore.

After two or three years, our holiday two weeks were spent in Hunstanton. Then a visit to Yarmouth put an end to holiday and the seashore, and the end of fortnights of sun and sea.

The reminiscence on airships became direct contact of flight in aircraft. It was the summer of 1937 probably that Aspley Guise had an appropriate field and ‘barnstormers’ rented the field and the aircraft, a pair of pilots invited the public to take a flight. Interest high, and Mother, together with Mrs Garrett, mounted their bicycles and pedalled to Aspley. The cost of a circuit around the field was a modest ten shillings per person. Buckle up, taxi out, take off, round back and a gentle settling to each and the flight is done.

It was about 1938 I cycled to Cranfield to see the recently built airdome for the RAF. The public had been invited to view the facility and the machines to be used. We saw Hurricanes and a lone Spitfire; a sample of bombers – Oxford and Anson.

An elderly bi-winged two engine powered, a bomber which was then in parachute training. Trained flight engineers would walk out onto the wing, to be clear of the engines, and pull the rip cord, allowing the parachute to pull away the trainer, and float to land.

Another visitor to Cranfield was a Bleriot light mono wing. The pilot was standing head and body above the aircraft.

With the war imminent, the Government arranged a trial evacuation of the cities to avoid bombing, particularly children. A variety of Londoners arrived by train and were packaged around the villages and settled briefly before their return home. I knew of no evacuees in Wood Street. London accents were heard, competing with Bedfordshire voices.

A year later the real evacuating began with World War 2. 1939 was the beginning of that war and much change. Uniforms common; rationing of food and services. I was near the age of military service. But 1940/41 brought a pleasant summer and a friendship with ‘Jelly’ Howard H. W. Heath. We enjoyed afternoon tea in their summer house, and smoked in there, for we were now old!

So in 1941 we joined the forces; Jelly in to the army, I to the RAF. I became a pilot, Second Lieutenant Jelly was part of the invasion of Italy. It was there that he was killed.”

Harry Buxton

Ontario, Canada 2009

If you have recollections of Woburn Sands before 1950, or perhaps know a relative who does, why not jot down some of those memories, or record them onto tape, before they are lost forever. That era will soon pass out of living memory. Or you could discuss the people and places detailed above with elderly relatives, and see if they can add any information. I would be pleased to transcribe any tapes you make and add memories to those here.

Webpage last updated Nov. 2018