The Summerley family, of Aspley Heath

I am indebted to Mr Ross Davidson, of New Zealand, for furnishing the history of the Summerley family, who once lived on Aspley Heath. I have reproduced three written histories from their papers, adding only some dates. The photos are mostly from their own collection of postcards etc, apart from a couple I have used from my own collection.

I read their story with mounting respect for their perseverance and courage. Their descendants are rightfully proud to have such character in their family tree. Although much of their story takes place just about as far from Woburn Sands as you can get, for a long time they still regarded it as ‘home’, and it makes an interesting example of how some families spread out.

The first part is a family history by Ella Summerley, born 1885, written as a letter for her sister’s children.

The Summerley Saga

In Sir Winston Churchill’s “History of the English Speaking People” he mentions a Bishop Somerie. We’ve always known somehow or other that there had been such a person and that we descended from him. That was 1066. There is also a castle near Luton known as “Someries Castle” Frances has seen it and it comes under that same heading.

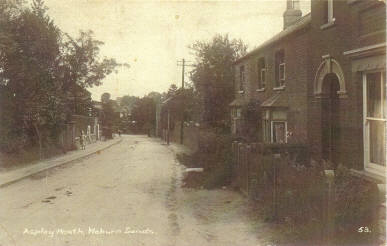

There is reason to believe that the Summerley family owned a large part of what is now the village of Woburn Sands in the 1830’s (1724 – 1812). According to hearsay the land was sold in order to pay debts caused by gambling, presumably to the Bedfords, who are great landowners. What was left was a piece of property on the Heath now known as Church Road. It began part of the way up and formed a division between Church Road and Sandy Lane, a turn off, but running parallel at a lower level. At that time there were probably two houses one at each end. The first real country cottage was over 300 years old. It had a thatched roof and very thick walls of brick and timber, and was white-washed outside. Inside, there was a kitchen, scullery, living room, and a small one divided by a partition from the living room. The staircase was a twisty one, leading up from the scullery to two bedrooms, each had a dressing room with a small window, a long wardrobe divided them which could be used by both. There were diamond paned windows in the kitchen and scullery and brick floors. The living room was board floored, and low ceilinged with thick beams across it; the window had iron bars outside. The house at the upper end was a big rambling old house and may have been the home of some of our honourable ancestors. They would be a Mr. and Mrs. John Paul Summerley.

As far as I know they had only two sons, John Paul and Henry; the latter married and produced one son and two daughters. Taking that family first, the son Alfred did very well in life, when he visited us he always looked well dressed. He married a delicate little lady, they had one daughter May. She was given every advantage a girl could wish for, being a student at Girton College. May was a fine looking girl with dark curls and dark eyes. She held an important post in the Department of Health. Alfred died, leaving May and her mother living together. Unfortunately May developed a mental illness and had to spend the rest of her life in a mental home. She died in 1950’s.

Henry’s eldest daughter Elizabeth, (Aunt Lizzie) became a school teacher and held a position in Dorsetshire. She married an elderly schoolmaster, named Spinney. They had one daughter Maud who was slightly deformed. The younger daughter Rhoda was in business in London. When she came home for a holiday, she was always dressed in the latest fashion, and often brought with her exquisite character dolls modeling the latest designs. She used to dress Maud so that the deformity was not noticeable. According to some papers Gordon found, the Summerleys go back to the 16th or 17th centuries and were connected with a Judge John Iredale who lived at one of the three Brickhill villages, he may have been related to the Bedfords, as he stabled his horses in the Abbey stable. Uncle Henry and his daughters lived in the rambling old house at the upper end of the property. What uncle did before he retired, I could not say, but when I knew him he had a marvellous collection of junk which kept him busy buying and selling. When Uncle died the junk disappeared, so did the old home and a very (ugly) up-to-date house was built where Lizzie and Maud lived. Rhoda retired and came to live with them. All three were very good Methodists and went to their Church in the High St. whenever there was a Service or anything else on. They greeted us when we met, but Maud was never allowed to come and play with us, or we with her. Sid used to call them the Three Bears. Aunt Lizzie had a gruff voice, Rhoda’s was softer and Maud had a regular squeak. Sid reckoned it was a sweet voice.

Uncle Henry’s elder son John Paul was born at Cateram is Surrey; he married Sarah Ann Bateman. They had seven children that I heard of: John Paul, Thomas, Louis Napoleon, Georgina, Emma, Hannah and another girl. The boys were sent to Charter House School, the girls evidently stayed home. Their father dealt in herbs, he became well-known for his tonics, pills, ointments etc., and was given the honour of the Freedom of the City of London for his medicines “Summerley’s Brown Powder”. From bits of conversation I gathered that the family visited France several times and had something to do with the French Court.

On retiring the family came to live in the cottage on the Heath, that grandfather enlarged considerably. Added on the cottage downstairs was a fair-sized hall containing a grandfather clock which we all loved, two Chippendale chairs, two marble busts on pedestals, one of Shakespeare and the other of Louis Napoleon King of France (Horace my eldest brother said we were a quarter French – and when I think of my two aunts Georgina and Emma who were both very dark I think there must be a connection; grandfather could easily have been a French courtier or a relation). There was also two coloured glass windows, the heavy front door and the staircase, also a door leading into the drawing room, which had a wall to wall carpet, horsehair couch and chairs, a round mahogany table, a large oval mirror with gilt frame of leaves and cupids which we wore never tired of looking at, also carved ceiling all round and in the centre. The staircase in two sections led to the front bedroom which was over the drawing room and bathroom over the hall.

The bedroom had a curtained fireplace and a large four-poster bedstead with curtains round it. The windows overlooked the village and beyond, it was so high. There was a large garden of herbs and fruit trees at the back. In front the garden ran down to a point. It held trees cut into various shapes, and all kinds of flowers

My Grandfather was a real old autocrat. Of the three boys, John ran away and joined the Army; the 7th Hussars, commanded by Lt. Kitchener. Thomas ran away and went to Australia. Louis Napoleon developed a lingering illness and died when he was 20. Of the girls, Georgina and Emma did straw-platting for a hat firm in Luton; they worked in a little room off the living-room known as the Platt room. Later it became our playroom. Hannah developed an illness and died young and a brother named John who was a mason married a jewess name Emma. We used to talk of Aunt Emma Bateman and Uncle John; he did the most beautiful work in marble. I remember being taken by Aunt Emma Summerley to see relations of Aunt Emma Bateman before I started school. They lived not far from Woburn Sands. They were two ladies wearing lots of jewellery, had rather big rosy faces and dark corkscrew curls down to their shoulders. Great-aunt Hannah used to come and see us. She wore a mantilla and a black poke bonnet. As she was stone deaf, people used to talk to her through the top of her bonnet. She was a dear little old lady. I was very small at that time and living with Grandma and Auntie Emma.

The other sister, which I mentioned above without a name, married a Sibley. She must have died fairly young; nobody ever mentioned her. Yet there were first-cousins living in London who were John, Jane, Annie and Emma Sibley. John married Sephy, a very smart lady with golden hair which cost a lot of money. They were well off and had a beautiful home. The only time I remember seeing John was at Aunt Emma’s funeral, he came to represent the London cousins. Annie and Emma remained single and were always spoken of as “the girls”. Jane married Alfred Page; he was on the staff of I & R Morleys, one of the City Business Firms. They had three children, Alfred, George and Mabel. They also were very comfortably off, our third cousins.

To come back to Uncle Tom who went to Australia, he married a quarter-caste Aboriginal named Pattie Brown. They had two daughters, Edith and Gladys who both became school teachers.

My father, John Paul, who went into the Army, was bought out by his father (the biggest mistake he ever made). He was put to learn the building trade, all of it, from drawing plans to putting the house together. But he was a frustrated man. He never got over being bought out. He married my mother Sarah Ann Hudson [in October 1875], much to her father’s annoyance; he cut her out of his Will. My father’s people thought that if he married the girl he loved, he would settle down. They lived in Packington St., Islington, London. Horace was born there. From there they moved to Fenny Stratford where Frances was born. From there they moved to Hardwick Road, Woburn Sands where I arrived three years later. [1885] The house belonged to Grandfather Hudson, and used to be a Wesleyan Chapel. It was partly built by my Great Grandfather who gave £60 towards. The next move as far as I know was to Sandfield cottage in Weathercock Lane where Hilda arrived. [born Dec 1889] It was a very small house. I remember we had measles together, Horace, Frances and I, in one room with the blinds down. Afterwards I was sent to Stewkley to stay with Aunt Fan who was my Grandmother, and Uncle Arthur Heady. They both worked for Grandpa Hudson who had a big farm at Stewkley. Fortunately for both of us there was a small field close to Sandfield Cottage where we played. Horace and I had lots of fun together while Frances was busy helping Mother in the house. Sometimes Father would take me for walks on Sunday morning. He looked so smart in black tail-coat, iron-grey trou, white waistcoat and top hat. (I still have his hat brush.)

When Hilda was born, I was sent to stay with Grandma and Aunt Emma. I was four and a half then, and was there for some time. There were more buildings on the land by that time in between the two original houses and when Sid was three weeks old, Grandma and Auntie moved up to the next house which was smaller and we moved from Sandfield to the big house – that is the one that had been enlarged. I’m afraid I didn’t enjoy the move. All the little comforts had gone from the old part, the carpet, the thick red curtains over the doors, the pretty table-cloth. Oh dear. (The reason why we were so hard up was because father was an alcoholic) He swallowed everything we should have had. It was a real tragedy. He never got over being bought out of the Army and occasionally he would put us through our paces, correct deportment, form fours, etc., march to time. We did everything he wanted on purpose to keep him at home. He and I did gymnastics together.

I would climb up and sit on his head or shoulders, let him swing me round by the feet. I danced to the violin of which he was a master. Otherwise we lived in a state of terror, depending on the mood he came home in. He would smash the violin to pieces, then spend the next day patiently putting it together again. He would kick panels out of the doors and have to mend them, he would pull the tablecloth off the table, crockery and lighted lamp would all tumble on to the floor and break. Why the house was not set on fire, I do not know, and however Mother stood it all, I don’t know. She said she took him for better or for worse and she would never soil the family honour.

We settled in our new home and attended the school which was just across Sandy Lane. When Horace was fifteen he left school and somebody found him a job as boot-boy to one of the big houses on Aspley Hill. The schoolmaster held a class in the evenings at his own house and gave Horace and the other boys a higher education than he could give them at school. Father was jealous of Horace. I’ve seen him throw Horace’s books on the fire. He could not sell the house we were in because it was to go to Horace. After a while the Solicitor at whose house he was working took Horace into his office. Some time later he left home and went to live in Luton and worked in a railway office. He came home for the weekends. On one occasion Father came home in a bad mood and was about to strike Mother when Horace put himself between them. Father saw red and pushed Horace out of the house for his pains. After that, Horace spent his weekends with Aunt Emma. We could go there to see him, but he did not come home. When Horace was 22 [1898?] he went of to South Africa.

The following is a copy of a letter received from Gordon about Horace’s life:

“On arrival in South Africa he worked with the then Cape Government Railways until 1906 when he came to Johannesburg. He then joined the Transvaal Consolidated Land and Exploration Company which owned many farms and land around the city. He met Mum in 1907 and they were married in Dec 1909. At that time he decided to study for his accountancy exam and become an incorporated accountant of England in 1913. From this time he never looked back. But he was very upset that he could not join the Forces during the First World War. He was offered a partnership in an accountant’s firm, but refused, preferring to accept the security of a good position rather than be his own boss. In later years he regretted this because the firm did very well, and with Dads personality it would have reached the top of the ladder. In 1931 the Company was merged with the biggest gold-mining group at the time, Land Mines Limited, where he became the secretary and remained there until he retired in 1945. He then joined the Board of one of the Building Societies and became chairman in 1948. In this capacity he did far more work than was necessary, leaving often at 6am inspecting properties in other towns. In fact, he worked harder then and with greater enthusiasm than at any time I had known him. It proved fatal, for in 1950 he had his first heart trouble and although partly cured, a year later and still working for the Building Societies, he began to decline.

He held on with remarkable tenacity until the very end. He was he same in sport, playing better when he was losing than when winning. He became champion of one club in 1930 and he won many competitions. When he gave up golf in 1945 he took up bowls, and within three years he was runner-up singles champion at his club. His powers of concentration were remarkable. He had many other interests, serving on the Church Council, for twenty years, and becoming a Church Warden, serving on the school Governing Body for 25 years. Interests in Professional Societies, some of which he took his turn as chairman. After reading your account of his early life, I now have the greatest admiration for his achievements.”

We can all be proud of Horace.

Frances left school when she was thirteen to help Mother with the babies. There were the twins, Mabel and Albert, [born Jan 1895] and later on, Christobel. [born Oct 1896] But when Frances was sixteen, she was given a job as nurse to the Pain children, two girls and a boy. The children’s grandfather and our grandfather had been friends. Old Mr. Pain made his money in the share trading business and our Grandfather helped him with the accounts. There were four daughters and one son, father of the children. Everybody predicted that the money held a curse, and it seemed so, for they all developed T.B. in some form and died. Frances stayed until she was not needed, then went to Mrs Swete whose husband was in India. Frances went with Mrs Sete and children to Rangoon. She stayed there for over a year, then caught typhus and had to come home to get well. Frances had lost all her beautiful hair but as she got well it grew again in pretty, tight little curls. When Frances felt strong enough she began to look round for a job. I was able to help there as I was running a dressmaking business at the time, and mentioned her to one of my customers, a Mrs Everest. Her relations were looking out for someone like Frances. So Frances went to Mrs. Carver, her husband had cotton plantations in Egypt. So for the next few years Frances took children, 3 boys and a girl, backwards and forwards to Egypt.

After Frances left home, I left school to help Mother which I did not do very well. I was far too much of a tomboy so I was sent to the village dressmaker for two years to learn the trade. There was no money attached to this job; we did not have to pay and were not paid. After that I stayed at home for a while. I was not strong enough to do anything in the hard work line. A night school opened at the school; I attended and studied three subjects, Art, Literature and either History or Geography. Then Aunt Emma reckoned I ought to be learning more about needlework so she found me a job in Bedford as improver at Pearmains, a large drapery store. There was a large workroom at the back of the shop where several girls worked under the guidance of Miss Gold, a job I would not have liked. I had a room with a friend of the family for which I paid two shillings a week. My pay was 10 shillings per week. Out of that I had to keep myself and pay rail fare to go home for weekends. It was only a half-hour ride. I left there when we were put on three-quarter time as the work grew slack and I stayed home for a time. I had a friend living in Ealing near London so went to stay and found a job in Sayers workroom at 10 shillings weekly. We arranged that I should pay the rent of the house (seven shillings weekly) and they would keep me, so I had three shilling to spend, a real fortune. Sayers were walking distance so there were no fares to pay. I stayed for a year or two then cracked up and had to go home. When I was 22 [1907] I opened a dressmaking business in the loft over Father’s workshop; it was a large room with windows all along one side. Father screened off one end for a bedroom. I had tried sleeping in the house in the playroom, but Father would sometimes be raring until the small hours and doing what we used to call the platoon march round and round in the next room so there was no sleep for me. For one night he was so bad and using the most awful language, I had got up and went to speak to him. I said “Dad, if you don’t stop we shall soon be in Hell. I can almost smell the brimstone.” He departed upstairs. The next morning Mother said “Don’t you ever do that again.” I said, “Then I’m not sleeping here any more.” and I didn’t for at least ten years. Mabel and May Barnes came to help me as apprentices, and we did very well until I felt I couldn’t stand Father any longer, he was always coming upstairs to beg for 2d., and I hadn’t the heart to refuse him, although he was much quieter.

Aunt Emma died early in 1911. So I left home again early in August, having just turned 25. I went to Hampstead to be a companion to a school girl aged 11, stayed about 18 months, then left, vowing I would never take on a job like that again. From there I went to Prestwood, Bucks., to live with a nurse friend, she was the district nurse. I stayed there until the First World War broke out, Aug 4th 1914. Nurse had to hold herself in readiness for war service. So through the kindness of friends I went to Southwold, East Coast, to help run St. Barnabus Rest Home. The staff were all leaving to work in munitions, and the house was being run by a superintendent, by gentlewomen. We managed quite well. We really had a very happy time in spite of almost being on the “Front Line”. We were bombarded from the sea and air, but escaped serious damage.

Hilda comes next on the family list, she was born at Sandfield Cottage [in 1889], a very pretty baby. Horace, Frances and Ella were all dark but Hilda was fairish. She had thick auburn hair, hazel eyes and fair skin which freckled easily, must have taken after Grandma Summerley, she was fair. Like her name, Hilda was always more or less in the wars. After she left school she went to the village drapery store as shop assistant, looked very nice in her black frock. I don’t know how long she stayed, but after that went to various other places in the same capacity until she landed in London to help in a crèche at Stratford. I must have been at Prestwood at that time. It was during the War that Hilda took home a young man who wanted to marry her. Father gave him one look and would have kicked him out of the house if Mother hadn’t stopped him. It was very late so he stayed the night and went off after breakfast leaving a disappointed girl behind.

Father was a very proud man in spite of his weakness. Later Hilda became engaged to a quarter master sergeant. I did not hear much about it until he was killed in France. Poor Hilda. By this time Frances had left the Carver family as the children were grown up and gone to Sir Arnold and Lady Wilson to look after two, a girl and a boy. Hilda was at a loose end, so Frances had arranged for her to go there too. It was at Brampton near Birmingham. Before that Frances had travelled to Persia as Sir Arnold was British Ambassador. She had a very interesting time. I was at Southwold. Hilda stayed for a time but soon had to be sent home as the job was not suitable.

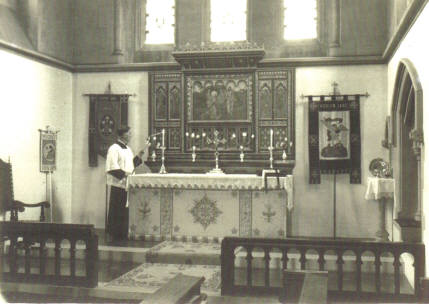

Sidney, as I mentioned above was born at Sandfield Cottage [in Aug 1892] which we left when he was three weeks old, and I was seven years old. I don’t remember much of what happened during those early years, I was learning dressmaking. We were terribly short of water and I had to go to the school pump and get two buckets every evening. I made puppet shows to amuse the children from nursery rhymes. Sid sang in St. Michael’s choir. They had an annual outing sometimes to the sea – we were 70 miles from the nearest sea. On one occasion [1902?] the outing was to be to Hastings on the south coast. Mother would not let Sid go alone, (not that he would have been alone) he was ten, so Hilda and I went with him. I was 17, Hilda 12. We left the house at about 2am and the train arrived in Hastings in time for breakfast. Dozens of chefs were frying eggs and bacon in the cafe. We had a lovely day and the sea was calm. I had never seen so much water in my life. We kept an eye on Sid but did not attempt to stop him over anything the boys happened to be doing. They spent most of the time in the sea. Our train let about 7.30pm and we arrived home at 3am the next morning to our mother’s great relief. She hated any of us being out of her sight for long.

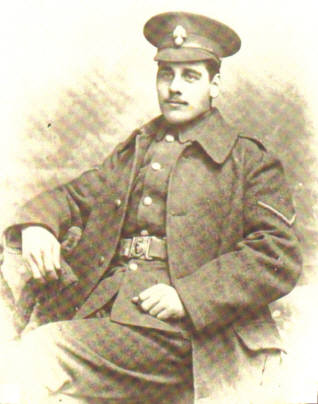

When Sid left school he went as a paper boy to W. H. Smith & Son, who had a branch in the village. Sid had a bike and did all the surrounding villages and farms. Mother was occasionally patching the seat of his pants. I remember making him a Norfolk suit, also an overcoat. Later Sid was taken into the shop and still later transferred to a branch at Hemel Hempstead. He and I met in London at Aunt Jane Pages house just as the War was beginning. Sid was considering joining up as a volunteer. He did later join the 13th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers who were training at Shoreham, and eventually went to France. He became a Lance Corporal and like so many other lads was killed by a bomb on July 17th 1916.

When Sid left school he went as a paper boy to W. H. Smith & Son, who had a branch in the village. Sid had a bike and did all the surrounding villages and farms. Mother was occasionally patching the seat of his pants. I remember making him a Norfolk suit, also an overcoat. Later Sid was taken into the shop and still later transferred to a branch at Hemel Hempstead. He and I met in London at Aunt Jane Pages house just as the War was beginning. Sid was considering joining up as a volunteer. He did later join the 13th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers who were training at Shoreham, and eventually went to France. He became a Lance Corporal and like so many other lads was killed by a bomb on July 17th 1916.

[See the World War 1 research on this website for further details of Sidney Summerley.]

The twins were born about two and a half years after we left Sandfield. [born Jan 1895] They were Albert George and Mabel Jane, so Frances was very busy helping Mother to look after them. Grandma and Aunt Emma were wringing their hands wondering how we should manage. Hilda, Sidney and the twins were baptised at the same time at St. Michaels Church. Albert was a lovely baby; he gave the vicar such a lovely smile during the service. He died of pneumonia at 14 months in April. Grandma had died the previous November. Mabel survived and a few months later Christobel arrived. As Father used to say, to keep Mabel company. He was very fond of those two. Mabel was very fair, Christobel very dark, they were known as Lily and the Rose. I don’t remember much about the growing up stage except providing some amusement.

I remember when I was a very small girl I was staying with Grandma. Aunt Georgina was being courted by a Mr Clark who was a widower. He used to come to take her out for walks in the woods. Little Ella went with them to play gooseberry. One day we were walking along a path with purple heather growing on each side. Aunt George and her swain were ahead of me, when I saw what I thought was a pretty stick lying in the heather. I went to pick it up and it wriggled away – it was an adder. The grown ups were so absorbed in each other that I said nothing about it. Eventually they married. Aunt George was a handsome woman and looked well-dressed. She used to wear a bonnet and mantle. Compare today’s fashions to that age group!

When Mabel and Chris were small girls together they spent a lot of time hanging over the front gate watching people go up and down the Heath. The vicar, Rev Russell Dickinson [vicar at Woburn Sands 1900 – 1901] was fond of them and always came up and had a talk. When Chris spotted him, she would call out “Hello Dittings!” and he would grin and come and have a yarn. We were very sorry for him – he had a beautiful wife but she was quite mental. The next Vicar wasn’t nearly so friendly. [Rev. Douglas William Henry, vicar 1901 – 1913] He was a very plain man with thick bushy eyebrows and when he was preaching the eyebrows used to jerk up and down like a Jack in the Box.

We naughty children used to call him “Jimmy Eyebrows” although I’m sure he was a saint. He really was very good, instead of letting us run wild as we were in danger of doing, he had us at the Vicarage, taught us to play croquet and clock golf. He instituted penny readings for all the young people to take part and taught us to sing so that we could give concerts and get into plays and charades. In fact we owe him quite a lot for helping us through those difficult teenage years, and we weren’t a bit grateful. Sunday school outings, instead of being in a large field with a huge tent were a trip to some other place so that we realised we were not the only pebbles on the beach. His wife, Mrs Henry, too was splendid; she had a Women’s Bible Class and other adult interests. There was nothing to interest young people outside of church affairs. No theatres or picture shows. The wealthy had tennis and golf clubs. These had to be paid for and when there is no cash, nothing happens.

I think Auntie Emma had a bad time nursing Uncle Lou. He died in the big drawing room and she never liked going in there. On holiday occasions Mother would always try to give a party in that room all to ourselves when we drank ginger beer and played totem with nuts; it was a gambling game of which Auntie thoroughly disapproved. Another holiday treat was going to Woburn Abbey, we had a donkey in those days which I rode. We strolled round the sculpture gallery and grounds and had tea with the Foxleys, Mothers people. Then Horace and his cobbers would start a paper chase through the woods, there were some parts nearly as wild as the New Zealand bush, so of course they led us that way. I didn’t think we ever had a whole garment on our backs. Auntie would take me in hand and tidy me up. Then there were some ponds in a field just outside the village where frogs spawned. We went there, fascinated by the frog’s eggs. In one of those ponds, so the tale went, was a sunken church. According to history, the Vicar was a very wicked man. One day, when he happened to be in the church, the ground gave way and the church disappeared, leaving a pond in its place. We always regarded that particular pond with great awe; there were no frog’s eggs there.

When I felt I was learning something, and being in the trade I could get materials cheap, and I generally fitted the two girls out with new frocks or coats so they were quite tidy. When Mab was old enough she used to look after some children on the Heath, then when I was living in Hampstead she came to London to a post as undernurse to a Mrs Size, but Mab was not happy there and on one of Frances’ trips to England, she took her back to Egypt as there was another baby arriving in the Carver family. While they were there the war broke out. In their spare time they both did Red Cross work in Alexandria. It was there that Mabel met her future husband James Leslie Hill. She brought him home on the very day that Mother heard that Sid had been killed. The wedding took place at St. Michaels Woburn Sands [Aug 1917]. I heard very little about them, I was at Southwold. I knew they travelled a lot, meeting relations on both sides. I did manage to spend the day at Cambridge where James was studying for his Commission. Then he was sent to Germany with the Army of Occupation, coming home and going back as permitted. They stayed at our old home and I was able to be there for Christmas. Eileen the elder girl was born at Woburn Sands. That was rather a critical business but both came through safely much to our relief. Eileen was five months old when they left for New Zealand. I went to join them two years later in 1921 when Mollie (Monica May) the new baby was four months old. James lost his right foot in an accident and had an artificial foot, but he was never quite the same again, it seemed to take something out of him. Mabel proved a splendid wife and mother. Their great love for each other helped them through all their difficulties. The two girls received a good education in Greymouth High School. Later Eileen entered the Post Office and Mollie did office work. When the Second World War broke out Eileen volunteered as a Voluntary Aid and was sent to Egypt. She was invalided home after Typhoid fever and spent some time in the Christchurch Sanatorium. Later on she went to live in Hastings, where she met her husband Noel Davidson. They were happily married and have three beautiful boys. Mollie stayed home with her parents, going in to work in Greymouth each day. They had moved across the Grey River from Dobson to Taylorville. James was a very sick man when he died in 1951. Soon after that Mollie went to live in Napier and Mabel took a trip to England which she enjoyed very much. She saw all the family over there, including Horace’s eldest son, Gordon and his wife Meryl who were on a visit to England from South Africa at the time. She also stayed with the Carver family for a few days. They had retired from Egypt, and lived in their home “Highlands”. Soon after this trip, Mabel came to live in Napier, sharing Mollies flat. I spent some weeks with them before coming to Australia. They bought a home later in Maraenui, Napier. Mabel was very happy there and was able to spend quite a lot of time with Eileen’s children whom she loved dearly. Mabel died in Napier Hospital in June 13th 1962 after a stroke, and almost 12 months later Mollie married Sam Haroldson, for which I am truly thankful. Previously Horace died in South Africa and Hilda went suddenly with a stroke, in 1957.

Now for Chris. When she was about 27 she came to stay with me at Prestwood. She hadn’t long left school and we thought it would be a change for her. However things didn’t work out that way and Chris went home again. She was a very beautiful dark girl and amongst other things we didn’t feel equal to caring for her. Chris found a job as a children’s nurse at Sheerborough, if I remember rightly. We were so scattered that we lost trace of each other, and had to depend on Mother for family news. Chris married a chemist named Row Herd. They ran two shops, one in Edgeware Road, London and the other on Cubitt Island in the Thames. Chris preferred the latter as she said she could make up a fathings worth of medicine for those poor people. During the War (2nd World War) they were bombed out twice and finally went to live in Crewkerne, Somerset where Row died of cancer. Chris carried on with the business they had stated, except for prescriptions. On my visit to England in 1950 I stayed with her quite a lot and we got to know each other better. Chris died of pneumonia in Crewkerne on Jan 24th 1964. Frances, who had been in hospital for over a year, died on Mar 24th 1964.

My time in New Zealand was spent in various places. The first six months were with Mab at Dobson, then two terms at a Girls High School in Auckland, from there to visit at the vicarage, Kaitaia, then to stay with the Maori Missionary at Pukepete, while there, being a shop assistant in Kaitaia, from these to the Maori Mission House at Whakarewarawa, from there to the Community of the Good Shepherd, Auckland where I spent the next 27 years. Then to the Community of the Holy Name, Melbourne, Australia. Horace’s eldest son Gordon and his wife Meryl have been to see me, Mollie and Sam have been to see me and Eileen and Noel have been to see me. What more could I wish for. Horace had three sons and one daughter: Gordon, Denis, Paul and Joan, Eileen has three sons: Ross, Keith and John. Father died on Feb 26th 1921. Mother died on June 20th 1945. Mabel died June 13th 1962.After Father died, Horace came home and arranged to sell the old home. Mother and Frances who had come home to look after her, moved up to the smaller house. Hilda couldn’t keep a job so was living with them. The next generation can carry on from here. “Never say die”

I’ve told you quite a lot about your Grandfather Summerley because I think you should know what happened to a good-natured, loveable man when he allows himself to become a victim of alcoholism. Don’t think too hardly of him, but take warning that it doesn’t happen to any of you. And he did love your Mother so much. I can still see him sitting in his armchair, nursing Eileen, and feeling as a proud as a peacock.

Ella Mary Summerley

The second part of the Summerley Story was compiled by Eileen Davidson and Monica Haraldsen, daughter of Mabel, in January, 1990, and is a more in depth story of the life of Mabel Jane Summerley. As detailed above, she was born in January 1895, in Aspley Heath, and her story shows just how far from Woburn Sands one family can travel in one generation…

John Paul Summerley married Sarah Ann Hudson in 1875. Their children were Horace, Frances, Ella, Hilda, Sidney, the twins Mabel Jane and Albert, and Christabel. This is mainly the story of Mabel Jane.

When the twins were about a year old, they became ill with pneumonia, and Albert, the bigger, stronger one, died. Mabel, small than Albert, and very delicate, survived. She had grey eyes and honey coloured hair and a very fair skin and was a great favourite with her father. Her younger sister by 14 months, Christabel, was dark, and they were known as the Lily and the Rose.

When Mabel was 17, she did a course in nursery-nursing at Sister Christian’s School for Nursery Nurses, in London. Her father paid a fee of twenty pounds for this course. Mabel then went with her older sister Frances to Egypt, where Frances was governess to the two Carver children and another baby was expected. This was Barbara Carver and Frances and Mabel had the care of all three children, Sydney, Geoffrey and Barbara. The Carvers had a cotton plantation on the Nile and lived in a large house in Alexandria. There were ten servants and the nursery had their own cook, washerwoman, and pony and trap. Their sole duty was to care for the children. When Mr and Mrs Carver went on holiday to stay with the Prince of Monaco, Frances and Mabel took the children. They had a wonderful life.

When the First World War broke out, they spent their off-duty time doing Red Cross work, meeting the hospital trains, dispensing tea and the Carvers took convalescing soldiers into their home.

One day, walking on the beach at Stanley Bay in Alexandria, Mabel met a New Zealand soldier who had been wounded at Gallipoli. He was James Leslie Hill and was convalescing from a wounded shoulder suffered on 25th April, 1915. Later, in England, after service in France, he married Mabel in Woburn Sands in the Parish Church of St. Michael and All Angels. Mabel first brought James home to meet the family, the very day that Sidney was killed in France.

Mabel was 22 and James was 23 years old. They were married on 16th August, 1917. At this time, James had been promoted to Sergeant. His battalion fought in the battles at Fler, the Somme, Messines and Brasseville. During this time, he was recommended for the Victoria Cross but received the Distinguished Conduct Medal, and was sent to Officer Cadet Training College in Cambridge, in January, 1918. His award was for operations in France and Flanders. The citation reads: “Awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. This N.C.O. has taken part in every action the Battalion has been engaged in, displaying on every occasion in a marked degree, high qualities of courage and leadership which have been a fine example to all ranks.”

He was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant 30th May, 1918. While James was in College, in Cambridge, where he passed out top cadet in his unit, Mabel took rooms there for the three months of the course.

On November 17th, 1918, six days after the Armistice was signed, while James was with the Occupation Forces in Germany, Eileen Mabel Frances was born in Melbourne House, Aspley Heath, Woburn Sands, a tiny baby, 4½ pounds in weight. She was the only Summerley grandchild born in England to John Paul and Sarah Summerley, his sister Monica May being born in New Zealand on 27th March, 1921. Horace’s children, four boys and a girl, were all born in South Africa.

James returned to England on 6th January 1919 and until he and Mabel returned to New Zealand with their daughter, Eileen was a great delight to her Grandfather Summerley. She was baptised in the Parish Church and her Godparents were her aunts, Frances and Ella. Eileen was six months old when the troopship reached Lytelton Harbour, in the south island of New Zealand. It was June, 1919 and a coach trip awaited the family. The coach and horses drove over the Southern Alps via Arthur’s Pass and the Otira Gorge, at times a terrifying journey over rough, narrow gravel roads. It was not until 1921 that the 7 mile long tunnel was completed and electric engines pulled the daily express train from east to west and back across the island, 150 miles through magnificent alpine scenery at both ends of the tunnel.

Their arrival in Dobson, James’ home township was a great shock to Mabel, coming from such a well-established country. The township was small and built on the banks of the Grey River, a very deep, wide river, subject to great floods in heavy rain.

James and Mabel moved into their home, a six-roomed bungalow and James was offered the position of manager of the newly opened Dobson Coalmine. Things looked good for them; Mabel made a special friend of James’ sister Daisy, a schoolteacher who had married and had a little boy only five days younger than Eileen. On 27th March, 1921, Monica May was born. Her Godparents were her Aunt Hilda Summerley (in absentia) and Aunt Christobel Hird.

When Monica, (often called Mollie in the family) was ten months old, she became ill with poliomyelitis during an epidemic and suffered a paralysed right leg. She was two years old before she could walk. Mabel massaged the leg with oil every morning for many years.

When Monica was still very small, the coalmine closed temporarily through lack of capital and another loan was floated in Christchurch. Meantime, James took a position as Manager of the Inchbonnie Sawmill, Ltd., and had the misfortune to be on the platform when the locomotive was approaching pulling logs to the mill. The platform collapsed, James was thrown across the railway line and the locomotive cut off his right leg just below the knee.

The Christchurch-Greymouth Express was signalled, stopped, and James was taken to Greymouth Hospital where he made a good recovery, having been in excellent general health before the accident.

James and his younger brother Ernest built a general store on the same property as the house, but a separate building and this was the family’s source of income until after the Second World War. A shop assistant and a storeman were employed and when Monica was four years’ old, Mabel took both girls to Rotorua where Ella was working as a missionary. She had come to “look after Mabel” just after Monica was born, but there was no suitable position for her in the district or in the town of Greymouth, six miles away. She was in charge of the Mission House at Whakarewarewa, three miles out of Rotorua, and it was there the family stayed, with Maori children as companions and playmates. There were no other white children in the village around the Mission House.

Monica was admitted to King George 5th Hospital in Rotorua and had surgery to stretch the Achilles tendon in her ankle and was in a plaster cast for four months. Mabel returned with Eileen after six weeks and Ella took Monica home after the four months were up. Monica wore boots and a caliper until she was twelve, then announced “If I have to wear boots, I’m just not going to High School.” She really meant it, so lace-up shoes were allowed and the hated caliper was done away with.

Each year the district, comprising Dobson, Wallsend, Taylorville and Stillwater, held a Children’s Fancy Dress Ball. Mabel made original and beautifully finished fancy dress costumes for Eileen and Monica who always took part and they won prizes every year in various categories. Mabel’s needlework appeared in exhibitions of work for the Country Women’s Institute, embroidered pictures, framed, applique and other forms of needlework. She wrote a lot of poetry, especially during the first two years she was in New Zealand. She said “I was homesick, I cried every night for two years.” She put it down in poems, then Monica’s arrival helped her to settle in her new home.

When the world depression struck New Zealand, the miners and sawmillers had very little money, business was poor and the shop assistant and the storeman had to be released. Mabel took over the counter and James who was able to drive the lorry with a hand-operated accelerator, delivered the grocery orders and did the accounts.

Throughout those years, Mabel was a wonderful wife and mother. Monica was in Brownies and Guides and Eileen was in Guides, being 12 when the movement began in Dobson. The girls attended Sunday School and Bible Class and Evensong at St. Saviour’s church. They both did well at school.

Mabel was involved in community activities: the Red Cross, Women’s Institute (and was a delegate for her local Branch at the Albert Hall in London when the Queen Mother spoke). She gave many a “travel talk” over the years about her varied experiences in England, Egypt, Monaco, and travels through France.

Mabel did beautiful embroidery and also made the girls’ clothes, having learned tailoring with one of her older sisters before doing her nursery-nursing course. Eileen and Monica were the best dressed children in Dobson, and were brought up as little ladies. The Hill family was always admired.

After five years at Greymouth High School and with several examinations, Eileen obtained a position in the Chief Post Office in Greymouth, and Monica following with similar examinations to her credit, became secretary-typist to an accountant in Greymouth.

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, Eileen began her Red Gross training in Greymouth Hospital. After passing several examinations and doing a year of practical hospital nursing, she was accepted for overseas service in a military hospital in Egypt. Mabel was very upset, she knew Egypt; it was NOT a good place to go. James said “You were there in the last war, and so was I. Now Eileen wants to go; we mustn’t stop her.” They were both very proud. At her farewell in the local hall, in his speech, James said “I don’t have any sons to send, but my daughter is going,” He was near to tears. He wore his medals, including the D.C.M, and said “I’ll wear them again on her return.” But he didn’t, because Eileen was invalided home after two and a half years after typhoid fever and pleurisy and was in Wellington Hospital for six weeks before a very quiet homecoming arranged by the Red Cross. Mabel’s hair had become white during Eileen’s illness, which was very serious.

[Eileen was asked by war artist Peter McIntyre to model for an official war picture of the ‘Wassies”, the W.W.S.A. – Women’s War Service Auxiliary]

Mabel once more came to the fore, nursing Eileen back to health and then had to say goodbye as the chest specialist ordered three months in the Sanatorium in Christchurch, followed by life in a drier climate than that of Dobson. So off to Hastings in the North Island and two years later, marriage.

Throughout the twenties, thirties and forties, Mabel continued her good works in the community. She was an examiner for the Girl Guides and arranged for her niece Thelma to have a dressmaking course to enable her to earn her living while caring for her sick mother until the latter died. Thelma continued her sewing until she retired. Mabel also did knitting, crochet, tatting and fine embroidery. Her hands were never idle. She made party favours for the parties of her girls and many items for Fetes and Fairs. With her training, she also gave talks to young mothers and also the not so young, on correct Child Care. When Queen Carnivals were held during the war, to raise funds for the War Effort, she made costumes for Eileen and Monica, who took part.

In 1946 James and Mabel sold their house and shop and moved across the Grey River to Taylorville to a house with a large garden, lawns and bee hives, which were to keep James busy for the rest of his life. He was still involved until the move with his positions as President of the school committee, President of the Returned Soldiers Association, an acclimatization Ranger, and a Justice of the Peace. He was also a Past Grand Master of his Lodge. The war years in the shop were a great trial to Mabel with rationing, coupons, shortages and some things quite unobtainable. Throughout she remained calm and busy, but it took its toll and she was exhausted when they moved. Many weeks passed before she felt her old self again.

James’ health was failing, an old wartime lung trouble as a result of being crushed between two military vehicles in Cairo in March, 1916. Mabel nursed him through many bouts of ill health. He was well enough to give Eileen away at her wedding when she married Noel Edward Davidson, of Hastings, on 6th September, 1947. Eileen’s wedding was a big event in the family, with 120 guests. Ella sent white Arum lilies for the church from Auckland in a long old-fashioned corset box (where did she get that box?) The gown was made in Hastings but Mabel made the veil and train of tulle, a headpiece of arum lilies and large Fresh lilies appliqued on to the end of the train which trailed on the floor. The wedding was in Holy Trinity Church in Greymouth and Monica and Noel’s sister Fay were bridesmaids. Ella came from Auckland where she was a sister in the Order of the Good Shepherd.

In March, 1949 Ross was born the first grandchild and Mabel travelled to Hastings to spend two weeks helping Eileen on her return from the Maternity Hospital. James was reluctant to have her go, he was far from well, and he died of cancer on 25th September, 1951. Eileen’s second child Keith James was born on 24th October, a month after James died. Mabel once more travelled to Hastings to look after Ross and help with the new baby.

In 1951, Ella returned to England for some months and contacted Summerley and Hudson relatives. She was very keen for Mabel to make the trip which Mabel did in 1954. She sailed on the S.S. Rangitane and spent several months with her sisters, Frances, Hilda and Christabel. She also saw her old school teacher, Miss Robinson, aged 90, about to leave England to live with her brother in Kenya. Mabel also saw Gordon and Meryl who were on a trip to England – this was a highlight of her trip home.

On Mabel’s return to New Zealand, she sold the house in Taylorville and bought a house in Napier, in the North Island, 12 miles from Hastings. Monica had been transferred to Napier in 1952, working in the Broadcasting Service. They lived together until 1962 when Mabel suffered several small strokes. She was admitted to Napier Hospital, suffered a major stroke on 12th June and died on 13th June without regaining consciousness. This was a great shock to Eileen and Monica but Noel helped with all arrangements. They informed the aunts, Frances, Hilda and Christabel, and Gordon in Johannesburg

In the eight years Mabel lived in Napier she spent many long weekends with Eileen and the grandchildren, Ross, Keith and later, John Edward, 4 years younger than Keith. She knitted numerous garments for the three boys and when they had birthday parties she was always there to help with the organizing and the work. Her parties were famous!

All her life, Mabel had many friends. She had a cheerful nature, a deep faith in God, and a quiet determination to support her husband whom she called Sunny Jim because of his sunny nature and great sense of humour. Her girls were her special responsibility and no one had a more caring mother.

Mabel and James were in love all their married life and they were wonderful parents.

Eileen Davidson and Monica Haraldsen

Lastly, an extended family history of the Hudson family, also by Ella Summerley

The Hudson Family Saga

Some time in the early 1850’s Thomas Hudson married Eunice… She presented him with 13 children. I only knew of eight. Sarah Ann, Emily, Frances, Margaret, Ella, Alwyn, Ambrose and John.

Eunice died at 35, leaving Sarah to care for the family until her father married Mary. Sarah used to work in the Woburn Sands Post Office. At 21 she married John Paul Summerley against her father’s wishes so he cut her out of his will. The Summerley family thought that by marrying the girl he loved J.P. would reform – it didn’t happen. 0f their ten children, seven lived to grow up to adulthood.

Emily married William Cooper a good hearted farmer, she was always called Aunt Cooper. They had one daughter Eunice (Ness) who used to come to her Aunt Sarah for advice over all her growing up troubles.

Frances (Aunt Fan) married Arthur Heady who worked for her father on his farm at Stewkley, Bucks. They had one son, Percy.

Margaret (Aunt Mag) married Ted Heady who had a baking business in Stewkley. His younger brother helped him, so did Percy. The younger brother was Walter. They had two children Connie and Ray. Once when they were playing round, Connie picked up a piece of dough, slapped it on to Percy’s face and said “There. Now you will never grow a beard.” He didn’t. Ness Cooper married Walter Heady. They set up a bakery in Dunstable.

My first visit to Stewkley was to Aunt Fan before Percy arrived. I would be about six, recovering from measles. She used to go and help at the farm; that was the first time I saw Grandfather Hudson. He was tall, has pale blue eyes and grey curls and beard. He was very fond of cats and rarely had less than a dozen playing about. They were all known as “Toskin”. Not long after that he sold the farm and came to live in one of his houses in Woburn Sands. He had a lot of property there. By that time he had married his third wife who had been his housekeeper. She had been Elizabeth Keyes. We knew her as Grandma Hudson. She always spoke of her husband as Mr. Hudson, even to us. I used to go to their home on Saturday mornings, peel potatoes, stay to dinner end receive 2d. for pocket money. Also I often went to stay with Aunt Mag at the Bakery. Uncle Ted was a very kind man. Connie married Henry – they had been sweethearts ever since they were small children, and were a very happy couple, I don’t know what became of Ray.

Ella, after whom I was named, died in infancy.

Alwyn, named after Lord Alwayn Compton, Bishop of Ely. He married Julia Tansley, a beautiful girl with honey-coloured hair and golden eyes. Amongst other things, he was a plumber. Julia ran a fancy shop. They had five children, Jessie, Tom, Mabel, Eric and Dorothy. Jessie married Charles Sinfield. He was house-agent for Lord Derby. She refused to have children because after they were grown up, another baby appeared and Julia had to help the doctor. She got a shock. The babe was so tiny; it only lived a few weeks. She was left a widow.

Tom married Hilda, but before Tom married, Uncle Alwyn died. He had lead poisoning. I remember his last days. They lived in a swanky home at that time, lower down Church Road. Uncle was in bed downstairs. The doctor came to see him about four o’clock one afternoon and told him he would be back with a nurse to operate in two hours’ time, (it was during the First World War). Uncle laughed, O.K. At 6 p.m. the doctor arrived with his nurse and a stretcher. The nurse was the Duchess of Bedford and she had taken her training and had opened a cottage hospital at Woburn and was helping the local doctors. When they saw Uncle, they knew it was hopeless; he had gone down too far. So they had to pack up.

The doctor was very sorry; he was fond of his patient. Several people came to see him. I sat in the kitchen with the parrot – one of those large blue and gold ones – he kept on calling out “Rats, rats, rats” – he knew something was wrong. We waited until all was over, then I helped the nurse to lay him out.

Tom carried on his father’s business and later became an undertaker. He was a dear man, so thoughtful, gentle and kind. People loved him. They had two children, Honeybun and Derek. I don’t remember the girl’s real name but she had honey-coloured hair. Derek married a pretty girl from Peru – he was studying to be in the Diplomatic Service.

Mabel, a lovely girl married Arthur Wenyon, a Methodist clergyman. They went as missionaries to India and had five children, Rosleen, Shiela, Moira, Eric and Reg. I saw the girls in 1951. Eric became a doctor, the girls all married well. Mabel died at the age of 35 – She had developed elephantiasis.

Eric Hudson, Alwyn’s youngest son, a fair boy with blue eyes: end shoulder length flaxen curls. His mother dressed him in Little Lord Fauntleroy style until he was five. When he was about 12, a boy kicked him on the hip; he developed a lingering illness from which he died at 16, before his father.

Dorothy died in infancy.

Rosaleen, Mabel’s eldest girl married. She had two children, Hilary and Charles. When she was carrying Charles she fell downstairs and Charles did not grow as he should have done – something went wrong. They were afraid he would be sub-normal. Anyway, Father Gilyn S.S.F. was holding a mission in the village and on his house-to-house visiting found Rosaleen and heard about Charles and their fears. Father took Charles, prayed over him, laid his hands on him and told them to pray, too; Charles went forward from that time, he is short, but active, and very sharp, and will probably grow taller. They have become firm Anglicans since then.

Grandfather Hudson died during the First World War. He left seven of us one hundred pounds each. We did not touch it as we wanted Mother to collect the interest while she was alive. After that, Frances saw that we each received our share.

Grandfather left assets to the value of twenty-four thousand pounds. Percy Heady was killed, also our bother Sidney duping the War. Tom Hudson died of Parkinson’s Disease. Jessie had it, too. The last time I heard of her she was in a Nursing Home in Bedford. I went to see Ness and Walter Heady in Dunstable when I was at home. Walter looked ill but he was so pleased to see me and I to see him. He has since died. Ness is a strong woman and will probably go on for years. She is older than me. So much for the Hudsons. The Hudson sisters all lived to be over eighty. I don’t remember much about Uncle Ambrose. Frances and I were at home together and we had been to afternoon tea with the Hudson Grandparents. After tea, Frances asked me to read her cup. There wasn’t much in it, except the outline of a large hand, so I told her she was going to shake hands with a big man. On the way home, we met Uncle Ambrose and shook hands and had a little talk. That is the only time I saw him. Uncle John and Aunt Millie lived at Welford. He was organist at the church, St. Mary the Virgin, they had two daughters Edith and Dorothy. We hardly ever saw them. Dorothy was a very precise little person; if she made a bed there wasn’t a wrinkle on it. Uncle Ambrose was a very large man and had a very large hand. I think he was a farther. Tom Hudson took us to see Aunt Millie, 88, through Northamptonshire, a lovely drive.

An artist named Thomas Hudson painted a very beautiful picture of one of the ancient Duchesses of Bedford; he must have been an ancestor, seeing how many of us have a talent of that sort.

On the occasion of Nessie’s wedding, we were all staying at Aunt Mag’s, Stewkley on the evening before; she plaited our long hair in dozens of plaits – tight ones. On undoing it the next morning, mine stuck out all round and had to be controlled with a big black bow. Jessie and I were 17 and Ness was 21.

Mother used to talk about the House of Buckingham and Chandos, the Foxleys and the Wootons with almost bated breath. Where the connection came in did not worry me. I am afraid, though they moved in this high circles of Society, they probably gambled away our inheritance, a sport they indulged in. I think they did a lot of drinking too, so what about their merits?

It’s just as well we were not brought up in the lap of luxury; we might have turned out a spineless crowd, whereas, having to make our way through life, enduring hardships, etc., we may hove grown stronger in character.

Ella Summerley, 1972

If you have found this story interesting, no matter where your roots lie, please consider writing up your family history as you know it, as you never know how interesting it will be to future generations.

Page last updated Jan. 2019.