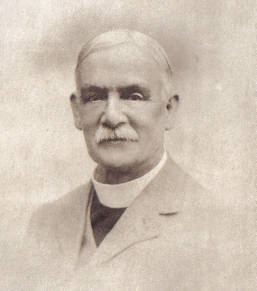

Charles Inwood – The Boy Preacher

Part of Chapter 1 of “Charles Inwood; his Ministry and its Secret” by Archibold M. Hay.

“Charles Inwood, the eldest of eight children, was born to Charles and Mary Ann Inwood on 25th March, 1851, at Woburn Sands, a village situated on the borders of Buckinghamshire and Bedfordshire; but it has not been possible to verify whether the house in which he was born stood actually in Buckinghamshire or Bedfordshire. The Inwoods were at this period of humble but godly stock. There is evidence that they had previously been a family of some importance for they were entitled to bear the crest of “a lion with a battleaxe,” a possible indication that they had at one time been identified with the royal service. But the greatest family treasure was a godly ancestry on both sides. The great-grandmother on his father’s side was one of the first Methodists in the district. She became a class leader, and when Sunday Schools were still a novelty, realising their value, she started one in her own house. From these early beginnings the Methodist Church at Woburn Sands had sprung. Her son, grandfather of our Charles, who had set up in business in the neighbouring village of Aspley Guise, was both class leader and local preacher. A man of original gifts and strong convictions he gave unstinted service to the church of his choice. On one quarterly plan of the Newport Pagnell circuit his name appears for no fewer than forty-six appointments, and these involved long journeys, so that it was often past midnight when he arrived home. His son, Charles Inwood, senr., followed his godly example, but for his livelihood chose another line of business, that of master tailor in Woburn Sands.

Charles Inwood’s mother, whose maiden name was Shimman, sprang from yeoman stock, owners of farm lands beyond Bedford; but by this time the family had become less prosperous, and her father held the position of bailiff, a steward of other folk’s acres. An ancestress of the Shimman family was a Huguenot refugee. She had been brought over to England by her parents as a baby girl during the persecution which followed the French King’s revocation, in 1685, of the tolerant Edict of Nantes. They had left lands, home, everything, and at peril of their lives made good their escape under cover of darkness to the French coast, the little babe being carried for ten miles slung on her father’s back. Then, hidden under tarpaulin, they were taken out to sea by boat, and found refuge on board an English vessel. In England the father and mother died shortly after of a broken heart, and the little girl, adopted by another Huguenot family, spent her childhood near Diss, Norfolk.

One other ancestor remains to be noticed, and this is his mother’s grandmother; for it was largely her disposition that his mother inherited. She had the distinction of being practically the only person of education in the village of her day. A woman of singular devotion and wonderful prayerfulness, she spent much of her time in deeds of benevolence and in visiting the sick, and it is to her possibly may be traced something of the spirit of devotion and prayerfulness so marked in her grandson, our Charles.

The village of Woburn Sands, with its less than a thousand inhabitants, bordering on Buckinghamshire and Bedfordshire, lies in a district richly favoured of God. It nestles at the foot of a low range of hills stretching into Buckinghamshire, covered with woods of pine and oak and beech. In the springtime these woodland glades were mosaics of colour. Primroses, anemones, bluebells and lilies created one rich scene of beauty, and on summer evenings nightingales made the leafy dells vocal with their plaintive melodies. It was rich, too, in religious associations. Twelve miles away to the north-east is Bedford Town, where two centuries earlier Bunyan not only dreamed, but blessed the countryside with a powerful ministry and suffered for it. Through those same towns and wayside hamlets passed George Fox, dreaming, ministering and suffering too, though unrecognised as a fellow-servant by the Bedford dreamer, whose eyes, alas, were holden. But in Woburn Sands lingered the fruit of George Fox’s ministry, a Quaker community with a little meeting-house. A century later John Wesley and his itinerant preachers brought life and holiness to these rural spots, and Methodism became an added feature to this corner of English country life; while scarce ten miles away, through country lanes, was Olney, where lived as vicar for thirteen years the converted slave trader, John Newton, and shared his spiritual experiences with William Cowper, that sweet singer alike of evangelical truth and rural England’s loveliness. And as young Charles grew to boyhood, the charm of that tranquil countryside, with its leafy lanes and hedgerows, its fields and brooks and spinneys, laid its hold upon him, so that he ever returned in after years with fresh zest and gladsome heart to the simple, unassuming beauties of rural England. Nor did its spiritual traditions fail to influence his growing mind. Woburn Sands, owing to its proximity to Bedford, almost claimed a share in Bunyan, and nothing was more natural than that at the unveiling of a statue to him there, in 1874, absent members of the family should take a deep interest in the ceremony, and that Charles should express his regret at his inability to be present; while in the village itself there was constant contact with those, who, following in the footsteps of George Fox, sought to direct their lives by the guidance of “the inner light.”

Charles Inwood’s parents, however, were both staunch adherents of Methodism. They were of strong, godly and affectionate character, and hard work and piety marked the atmosphere of the home. The tailoring business was prosperous and might even have been more so, but for their open-handed generosity to others and the father’s lack of robust health. Moreover, he regarded his business merely as the means of livelihood and support of the growing family; the main concern of his heart was the advancement of God’s kingdom. A local preacher in the Methodist connexion, he threw himself whole-heartedly into preaching the Gospel, possibly even with an industry and enthusiasm greater than that which he brought to his business, for his correspondence makes mention of his tailoring far less frequently than of his Father’s business. Many a Sunday saw him tramping long distances, almost too far for his strength, to surrounding villages, where his preaching met with a ready acceptance. Thus, he carried out his ideal for the Church of a voluntary ministry of laymen. He was an ardent supporter alike of the missionary enterprise and the temperance cause, and had even suffered violence in support of the latter. He was a man of great gifts and wide sympathies, and his counsel and help were eagerly sought by many. Thus, he spent himself, his strength and his means for others, and it was not surprising that upon his death, at the comparatively early age of forty-nine, recognition came to him in the privilege of interment in the Quaker burial ground, reserved usually for members of that community alone. The home was always open with a welcome for the Methodist preachers, both itinerant and local, and it was ever regarded a privilege to minister hospitality to these earnest servants of God. Simple-minded and sometimes barely literate they might be, but they had God’s recognition and favour in the blessing which rested upon their labours. Nor was the mother a whit behind in good works. In addition to family duties and the hospitality of the home, she ministered constantly with her own hands to the needs of the poor and sick, not infrequently denying herself in the so doing.

But chiefly did she excel in the unhidden ministry of prayer. To that cause may be traced perhaps an outstanding blessing which came to her husband on his wedding day. Certain it is that she dedicated before birth her first-born, Charles, to the Lord, and to her prayers as much as to her husband’s zeal and example must be ascribed the fact that of five sons four dedicated themselves to the ministry. It was to her in his letters throughout her life-time that Charles revealed his deepest aspirations, and to her prayer help that he turned as each fresh phase of service opened before him in his early ministry. And she too followed his course not only with the wealth of a mother’s love but also with the aid of a praying saint. It is, perhaps, significant that her son bore a greater resemblance in features to his mother than to his father.

Reared in the atmosphere of such a home, it is hardly surprising that Charles was converted at an early age. Education in the rural England of seventy years ago was in a backward condition, but in the adjacent village of Aspley Guise facilities existed for acquiring the rudiments of education in a British school; a free school supported by voluntary contributions of Nonconformists, and distinct from the National School where religious instruction was in accordance with the teaching of the Established Church, and to this he was sent. Writing of this school in after years he says: “What little school education that is useful to me and most impressed upon my mind is that which I received at the British School. Though small, it was a firm foundation.” And his gratitude expressed itself in the practical form of a subscription to its funds for several years. It was during his attendance at this school, and at eight years of age, that his conversion took place. A work of God was taking place in the neighbourhood, resulting in the conversion of some of the elder pupils. They thereupon started a prayer meeting in the school and invited Charles to join. So greatly did this impress the susceptible lad from the Methodist home that he returned that evening to kneel by his bedside, seek forgiveness and there and then receive assurance of pardon. From that simple act at eight years of age it is true to say that he never looked back, and it remained a bright and glad memory with the passing of the years.

In his teens he was apprenticed to his father’s trade, and daily in the workshop was forced to mix with those whose habits and talk the boy’s soul loathed. The confinement, too, began to tell on his health. Sundays, however, brought a joyous release, as he accompanied his father to service in some neighbouring village, and helped with his clear young voice to raise the singing. Soon, very soon, the boy was following in his father’s footsteps, for at fourteen years of age he started his apprenticeship at that trade of preaching which was henceforward to engross his life-long energies. And ere long he was known throughout the district as the “Boy Preacher.”

His father’s indifferent health seemed to necessitate Charles’ continuance in business, and a branch shop opened at Fenny Stratford, a town four miles distant, where he and a younger brother were put in charge, appeared to lay an indisputable claim upon him. But God’s call to give himself entirely to the ministry was challenging his obedience with an insistence which would not be gainsaid, and the father, recognising God’s call of his son, surrendered the cherished hopes of his help in the business. An engagement was therefore sought for him as a hired local preacher; but the first opening which presented itself was lost through temporary wavering in his father’s consent. The lad, however, was not to be gainsaid, and informed his father his determination to accept as the leading of God the post which next offered itself. To their amazement the offer came from South Ireland. Thus, it came about that the 23rd September, 1869, saw his arrival, at eighteen years of age, at the remote town of Cashel, in out of the way Co. Tipperary.

To live in Cashel was isolation indeed those days. The town itself was four miles from the railway, in a sparsely populated district, and Clonmel, the circuit town was a fifteen miles’ drive away in an opposite direction. We are fortunate in possessing a portion of a precious diary, which, together with many letters, covers this period of his first nine months’ residence in Cashel, and enables us to share with him some of the experiences of those early days. We can picture that first four miles’ drive from the station to Cashel after a stormy crossing. He would pass through beautiful country, unsurpassed in the richness of its soil by almost any other part of Ireland, yet, with the exception of a few prosperous farmers and traders, remarkable for its poverty and dirt. He writes: “The place is the dirtiest I ever saw.” Arrived at his destination, he would feel himself to be in an almost foreign town. Of its inhabitants less than 10 per cent, were Protestant, of whatever denomination; the rest owned allegiance to the Roman Catholic Church, whose churches and institutions, priests and nuns met the gaze at every turn in Tipperary. The mass of the people were sunk in such mental and spiritual poverty that there was hardly any county in Ireland where superstitions, beliefs and practices were more prevalent. It is no wonder that he writes: “Nobody that is not here can understand the opposition we have to contend with; it is terrible.” Verily, the little flock in the Protestant churches had to struggle for bare existence. The impression of being in a foreign land was heightened, too, by the bitter anti-English feeling then abroad. The Fenian movement was gathering force, and the elections held in November were signalised by the arming of the police, the drafting of troops into the town, and the reading of the riot act; while their outcome was to choose as the local representative at Westminster one who had been sentenced to gaol for life in connection with Fenian disturbances. And even after the elections the agitation arising from the introduction of the Land Tenants’ Bill, Gladstone’s first determined effort to take the conciliation of Ireland seriously in hand, kept feeling running high. There was some excuse then for the nervousness betrayed by his home folk that his work involved so much driving alone about the country.

But, at any rate, amongst the Methodists he could be sure of a warm welcome; but what a tiny handful of scattered folk they were! Methodism had come to Ireland in the person of John Wesley, in 1747, and by constant subsequent visits he had sought to include the island in his “world-wide” parish. He put in an amazing amount of hard work, there as elsewhere, and under singularly perilous conditions, but though he is able to say of the people, “For natural sweetness of temper, for courtesy and hospitality, I have never seen .my people like the Irish,” yet he recognised their peril and adds: “The danger is that the Word should not take deep root, that it should be as seed falling on stony ground.” And so there had not been the response to Wesley’s teaching that the initial eagerness to hear might have suggested, and it was indeed a struggling cause in many a country district in Southern Ireland.

Charles Inwood thought so, too, in his first introduction to it in this eventful year of his life. His congregation was drawn from villages three, four, seven, eight and even ten miles away. And so poor were they that the burden of his board and lodging was undertaken by three different families, to whom he went in turn, week by week; a sufficiently difficult arrangement for one who was eager to study.”

The rest of the book is filled with Charles’ experiences as a preacher. He stayed a year in Cashel, before returning home to Woburn Sands in July 1870. By September, he had accepted a post as hired local preacher in Buckingham. The work here proved so busy, and living expenses so high, that in July 1871 he returned to Cashel in Ireland again, the beginning of 33 years working in Ireland.

List of Appointments held by Rev. Charles Inwood, D.D. in the Methodist Church of Ireland:

| Appointments | |

|---|---|

| 1869. Cashel – Hired Local Preacher 1 year | 1885. General Mission Dublin 3 years |

| 1871. Cashel – Hired Local Preacher 1 year | 1888. Rathmines Dublin 3 years |

| 1872. Wexford – Probationer 1 year | 1891. Kingstown Dalkey 2 years |

| 1873. Abbey Street Dublin – Probationer 3 years | 1893. Armagh 1 year |

| 1876. Carlisle Mem. Ch. Belfast – Ordained 1 year | 1894. Knock Belfast 1 year |

| 1877. Tullamore 3 years | 1895 University Road Belfast 2 years |

| 1880. Centenary Ch. Dublin 2 years | 1897. Without Pastoral Charge 3 years |

| 1882. Drogheda 3 year | 1900. University Road Belfast 3 years |

| 1903. Supernumerary. |

He had met his wife, Emma Jane Lumley, while working at Drogheda. She was the daughter of Mr William Lumley, a local merchant and Methodist. Very few further details of his family life are given in the book; but it is noted that they had two sons and two daughters.

Even before he had finished working in Ireland, he had begun to travel more extensively around the world, preaching wherever he went, as this itinerary shows:

| Travel | |

|---|---|

| 1893. Canada and U.S.A. | 1909. South America. |

| 1895. French and Italian Riviera. | 1910. Central Africa. |

| 1897. Canada and U.S.A. | 1912. U.S.A. |

| 1898. Sweden. | 1912. Jamaica. |

| 1898. Germany. | 1912. South America. |

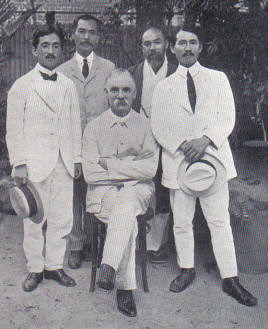

| 1898-99. China. | 1914. Algiers. |

| 1899. Sweden. | 1915-16. Egypt. |

| 1899-1900. India. | 1916. Japan – Formosa – China. |

| 1900. Egypt. | 1920. Ceylon. |

| 1900. Palestine. | 1920. India. |

| 1902. California. | 1920. South Africa. |

| 1903. Switzerland. | 1921. France. |

| 1904. Germany. | 1921. Spain. |

| 1904. Wandsbeck. | 1922. U.S.A. |

| 1904. Biarritz. | 1922. Japan. |

| 1904. South America. | 1923. Egypt. |

| 1905. Blankenburg. | 1923. Belgium. |

| 1906. South Africa. | 1925. Spain. |

| 1907. Australia. | 1925. Denmark. |

| 1908. New Zealand. | 1926. France. |

| 1908. Turkey – Asia Minor. | 1926. Belgium. |

| 1908. Palestine. | 1928. Holland. |

| 1928. Czechoslovakia. |

In 1902, he became unwell with a throat infection. He went to California to see his two brothers, who were preachers with the Methodist Episcopal Church there, and in three months he was cured. In 1911, he published “An African Pentecost: a record of a missionary tour in central Africa”.

His mother died while he was in Alexandria in 1900, and she was buried in the Quakers grave yard at Woburn Sands, beside her husband. In July, the local paper noted that “The Rev. Charles Inwood has returned from his visit to India to preside at the memorial service for his mother. He says he saw a bed in an Indian hospital, with a plaque engraved with the name ‘Woburn Sands’. On asking, he found it had been funded with the generosity of Mrs Stuart of Woburn Sands.”

His youngest son, Charles Hawkins Inwood (born 1891), was an official of the Railroad at Altoona, Pennsylvania, U.S.A., and came back to England in October 1914 to join up to a Public Schools Battalion. He was a 2nd Lieut., of the Machine Gun Corp., and was killed instantly whilst going to rescue his servant who had been wounded, just outside St. Julier. His parents address in England is given as 14 Hove Park Villa, Hove, Brighton.

Charles Inwood was made a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and in 1922 was conferred a Doctor of Divinity by the University of Southern California. He died in October 1928, aged 77.

Page last updated Jan. 2019.