“In Good Service – Margaret Jackson, Housemaid of Buckinghamshire”

I am very grateful to the publishers, David & Charles, for their kind permission to reproduce this part of the 1997 book ‘Tales of the Old Villagers’, by Brian P. Martin.

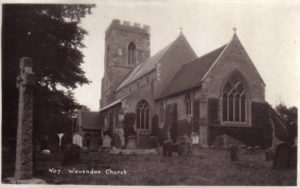

It gives a fascinating and detailed insight into what life was like in the early to mid-1900s in Wavendon, from the perspective of a house servant. It records her childhood, school days and early work experiences locally in Wavendon Rectory and Wavendon Tower. Margaret had previously written a short history of St. Mary’s in 1989, in partnership with Ruth E. Davies, a campanologist.

In pre-war days of relatively cheap labour virtually every big house in every village had a generous complement of staff. Among the most indispensable were the innumerable housemaids, girls from mostly humble backgrounds who generally expected very little out of life and who knew their place in the ‘pecking order’. Some were cruelly maligned as ‘mere skivvies’ yet the stalwart domestics of those days generally had considerably more social standing than their modern counterparts. Their pay may have been abysmal, but in a good house they were virtually part of their employer’s family and inevitably displayed great loyalty and took much pride in their work. Other, newer forms of employment may have tempted with higher wages, but they could not offer dignity as Miss Margaret Jackson recalls: ‘There were new factories in our area, but on no account would Mother let me go to them as that was considered degrading. Mother had always been in good service herself; you could tell that by the way she spoke and conducted herself.’

Thus it was no surprise that, at the age of sixteen, Margaret followed the family example. Her three older sisters were already in service and her younger sister would soon follow suit, but Margaret was luckier than most in securing a local position. With her sisters working and living away (they only returned for holidays), pressure on the family purse and space at home had already been reduced, but Margaret was still required to live with her employer. Remarkably, she was destined to remain in her native village until the present day.

Edith Margaret Jackson was one of seven children, and always known to her dearest as Meg. She was born on 13 July 1913 at the Buckinghamshire village of Wavendon, ‘within the sound of the anvil’ as her cousin was a blacksmith there. Sadly she never really knew her father, a timber worker and general labourer who helped build houses in the village; he suffered consumption (tuberculosis) for years and died when Margaret was only three. Fortunately, Margaret had a ‘wonderful’ mother to care for her, and she remembers her early years with great nostalgia.

‘People helped each other much more then, and we were well supported by the love of our neighbours when Father died. Also, they made up for much of what we missed out on financially, people often bringing us things such as fruit and eggs. My earliest recollection is of a very simple gesture: picking a strawberry and showing it to Mother. The garden had everything in it in those days: a really lovely Blenheim, a greengage tree, plums, lots of gooseberries, and that lovely maiden’s blush round the door – roses don’t smell like that now.’

Margaret’s grandfather also died young, in his forties. He once kept the village post office, but was better known as PC Collyer, the last resident policeman for Wavendon. However, he had not looked forward to being posted there because the place was notorious for ‘the rough element’. The area was once known as Hogsty End, combining most of Woburn Sands with Wavendon. Wavendon is unusual in having had only three clergymen in over 150 years, and the strength of the church there had a great influence on Margaret from an early age.

‘For a start we were blessed with a Church of England school. Every year we had an exam for the Bishop’s prize, and once I was runner-up. The dear old rector always used to go up to London and choose the prizes himself. I suppose you could say I was clever at school, and I was certainly very happy there. The only lesson most of us hated was learning to sing with the modulator. We always started school with assembly, with a hymn and prayer, and the last lesson of the day was from the scriptures. That school served the village well then, with about seventy pupils within walking distance; now, however, it would have closed long ago if it weren’t for people dropping children off in cars. It’s all very different from when every pony and trap used to come along with candles in their lamps, and those of us on foot often had to go across the fields by full moon or lantern light.’

Some seventy years later, Margaret still treasures a few of her school books, not least her prize volumes and one containing her painstakingly prepared sewing patterns. She also cherishes thoughts of ‘the many poems we used to learn by heart, all about Mary, Queen of Scots and brave Horatius. The standard was very high.’

But of course not everyone was academically inclined, including Margaret’s brother Hugh. ‘Opposite the school was the slaughterhouse where the pigs were taken, and if “it” happened in the afternoon all the boys would go out to watch. They used to stand on the forms at the back of the class with their eyes out the windows. One day the teacher said to Hugh: “What’s more interesting out there?” “Harry Gurney comin’ up the road with a load of muck, sir,” he replied. Hugh was only ever interested in farming and couldn’t leave school quick enough. He and the other boys used to make the ink every week, using a powder, and us girls often got splattered. Mind you, the teachers weren’t all perfect then. If our schoolmaster knew the Whaddon Chase hunt was meeting anywhere near he’d get off after them on his ol’ bike, a lady’s model. So the boys thought they’d go too. But Mr Buxton always knew who was missing and was heavy with the cane. Then one day he went berserk and the boys had him on the floor. Everybody was wringing their hands and didn’t know what to do – but next morning nothing at all was said.’

The Jacksons lived in a simple cottage, one of fifty-three homes which have disappeared from the parish since Margaret was a girl. They encountered considerable hardship, although Margaret also remembers the many happy days during her childhood, just after the Great War.

‘In 1921 the village purchased a disused Canadian army hut, and as the first scout group had just been formed it became known as the BP (Baden Powell) Hut. The day it opened was a red letter day for us. I can see it now, and all the fun times we had in it. Mothers, fathers and children were all so delighted to join in the festivities, playing musical chairs and tripping up the long room with Charlie the postman on the piano and all singing “A hunting we will go…”. The scout group had a band in which my brothers Fred and Hugh played the kettle drums. When they marched through the village with flags flying we sisters ran alongside trying to keep up. Now that hut and the school have gone.

‘As we paid under £5 a year rent we received “the parish coal”: one ton a year dumped at your gate free of charge, courtesy of the Duke of Bedford’s estate. We had lovely great lumps then and the boys barrowed it in to the barn. And if you had more than a dust-panful of dust to sweep up after, you’d complain! Today there aren’t the number of people applying for free coal, and if you get two hundredweight you’re lucky.

‘When the milkman came, by pony and trap from a local farm, he often had a rabbit for a shilling, and that would do us two meals done in a brown earthenware jar in the oven. Then Tommy Allen, the rag-and-bone man who came round with a donkey, would give us sixpence for the rabbit skin, so the rabbit really cost us only sixpence.

‘On Sundays Mum stayed home to cook while us children went to Sunday school and church. When we came home we had lovely beefsteak pudding and vegetables, and this would fill us up so we didn’t want so much roast beef afterwards, making it a cheaper meal. That was the general trend for all the working people then, and it was the only time of the week a family would sit down together. There was no electricity, and everything was cooked on a coal-fire range. We never had a sweet after Sunday lunch, but Mother would have made a pie or tart on the Saturday and we’d have that with cold vegetables and other things after church on Sunday evening.

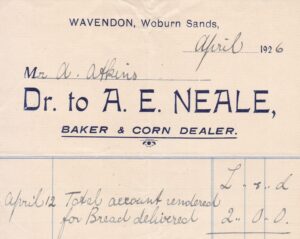

‘Mr Neale, the baker, used to go round the houses, and on a Saturday he’d bake your cake for you. We used to love going in the bakery to hear the crickets. In the week there was always jam roll or spotted Dick on the menu. And in the winter when we came home from school we would open the door and smell dripping toast for tea – that was a lovely thing to greet hungry children. And darling Mum was always there to welcome us.

‘We lived very close to the school and always envied the “dinner” kids – those who lived more than one and a half miles from school. They always brought the first spring flowers, the crab blossom, and if snow was coming or a thunderstorm was threatening they’d be sent home early.

‘No matter how poor we were we never wore on Sunday what we wore on Saturday. We always had pretty little cotton dresses and pinafores, a lot made at home by my sisters, and nice little warm coats in winter. We had long plaits, but our hair was loose on Sundays, with a bow.

‘During 1920 terrible diptheria swept through the village; we all had it and the school was closed. Afterwards the whole school was disinfected, and that smell was in every pen, pencil and book for years. Darling Mother nursed we, her three young children, alone for fifteen weeks; and then, on a lovely day in February, a dear young cousin called Rosy brought the first snowdrops. She put them on a broom and lifted them up and I opened the bedroom window and took them in. It was so wonderful to smell those flowers and the fresh air after being indoors for so long. I can smell them now.

‘One of my hobbies was recording the weather and I used to measure the winter solstice with the almshouse roof, in the yard nearby. We had some real winters then! We always had a slide in the road, and one lady used to come out to peel her potatoes on the ice to make it melt. We also had our whipping tops – known as “window breakers”- and hoops, and we used to go all the way to Walton. The “snob” (Collins the cobbler) used to put the peg in the top for us, and when we sang “Uncle Tom Cobley and All” we used to end up with “Snob and all”.

‘In the autumn we used to go acorning for Mr Gurney’s pigs, and if there was a gale the children always went “sticking” for fuel. In those days I don’t think anyone complained when children were missing from classes because the schools were so crowded. I still can’t pass a bit of rotten wood.’

Despite the hardships, there were several annual treats to look forward to. For the Jacksons, the highlight of the summer holiday was a trip to Bedford, ‘a lovely little town then’, where two of Margaret’s sisters were in service. ‘We’d go into Woolworth’s there and nothing was above sixpence. I still use the little birthday book I bought then.’

But for some thirty children of all ages the highlight of the whole year was the choir treat and Margaret remembers it well.

‘Margate was the favourite destination. The train left Woburn Sands station at 5.30am, so we always used to wake everybody up with all the noise we made, and we would reach the coast at about 9.30. The first thing we did was hire a deckchair, and I always ended up sunburnt. Then there was a lovely lunch and a fish-and-chip tea, and we always bought presents for those left at home. We generally returned about midnight. Dear old Reverend Phillpotts paid for it all – he even gave us our spending money. That went on right up to 1939.

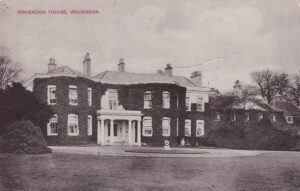

‘The choir always went round carol singing on Christmas Eve: first we went up to the Rectory, then Tower House, and ended up at Wavendon House about 10pm, where there’d be a lovely supper laid on for us.

‘The bellringers always started getting ready for Christmas on 5 November. At first they practised only once a week, but it ended up being daily. Nowadays they’re not allowed to ring on Christmas Eve for fear of disturbing people, but us children used to love lying in bed listening to them: it was part of Christmas.

‘We never had much in the way of Christmas presents. At first we just had a sugar mouse, an apple and orange, and perhaps a few pennies, all in the toe of a stocking. But later there might be a book by Angela Brazil or a jack-in-the-box, and if we were very lucky a flaxen-haired doll peeped out the top.

‘But getting ready for Christmas was half the fun, with all that fruit to be washed and puddings and cakes to be made. There were three shops in Wavendon then and one was run by a dear old spinster, Miss Stradling. People used to say: “Have you seen her window? She’s decked it out for Christmas.” And what a lovely job she made of it. In the middle was an old oil lamp and we children used to gaze in at all the wonders carefully placed around it, looking at what we hoped to get for Christmas: dolls, toy pianos, skipping ropes, tops, dulcimers and nets of sweets. And when Miss Stradling put the light out in the darkness of the evening it was a sign tor us all to go home. We used to buy our wooden hoops there, too. There was everything in that shop – even a chair to sit down on if you were tired.

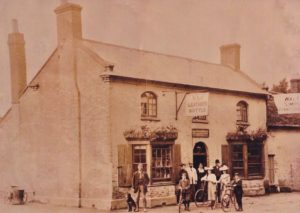

‘Then there was Percer’s shop, where they had a great many ramshackle old bikes you could hire one for a halfpenny for half-an hour to learn to ride. If we were lucky we had a penny pocket money on a Saturday, and what you could buy for a Penny then was nobody’s business!

‘The other big treat was the Sunday school party, usually on about 1 January in the school. We only had plain bread and butter, plain rice cake and fruit cake, but it was lovely because we sat down with the lady from Wavendon House, with her fine china and silver teapot. Wavendon House was the squire’s house and Mrs Bond who lived there was like the Queen Mother to us.

‘After the meal the seats were rearranged, out came the harmonium and we sang carols while we waited for the parents to come for the marionettes show; everybody was invited and it used to be packed out. If we had anything in the village today hardly anybody would turn up, but in the old days everybody went to everything.

‘When the puppets were over we had the presentation and prizes for the marks we had gained in Sunday school. And we always finished with the national anthem, and three cheers for the rector. And when we went outside all the children were given an orange and a bun. We’d sing the national anthem on any occasion then, and on Empire Day we’d salute the flag, too.’

Like so many clever children of her generation, Margaret was denied the opportunity to go on to higher education because her family just could not afford to keep her. As a result she left school at the customary age of fourteen ‘in floods of tears’. But there was no full-time job for her to go to at first, and she was sixteen before she went to work as a housemaid for widow Waudby at The Old Rectory. Margaret describes those early days in service:

‘l was a general help to everybody, but especially the cook and senior maid. There was also a chauffeur, a gardener and a garden boy. Mrs Waudby was a marvellous artist who had exhibited at the Royal Academy, and she had over seventy paintings in the drawing room alone. There were others all over the house and they took us ages to dust!

‘My wages were about 10s. a week, and I slept right at the top of the house. In 1939-40 it was so cold the water tanks were frozen solid, and at night, Edith the maid and I would be covered in ice where we’d breathed. So we had to go down and sleep in the guest chambers. In 1940 three lovely young men from the RAF were billeted with us, but they didn’t mind the cold so much.

‘The main reason why housework was much harder then was that there was no electricity, and no such thing as vacuum cleaners; it was all lamps and candles, dustpans and brushes. But we still managed to have fun.

‘Edith always called Mrs Waudby at 7.30am and took her hot milk. She also took up hot water for washing, in lovely brass cans which we had to clean every day along with the silver candlesticks. Mrs Waudby took breakfast in her room at 9am and she’d be down by 10am, going straight into the oak room in winter. Her great creed was: “You never got a cold through being cold”, and as a result there were only ever four fires lit in that great house, including the kitchen range. But at least the house was lovely and cool in summer.

‘Poor old Mr Paxton the coachman/chauffeur (a descendant of Sir Joseph Paxton) used to be perished when he got down off the carriage – but Mrs Waudby was always nice and warm inside with a lovely sable rug. Even so, he hated it when he was given a car. There was also a brougham and a two-seated, two-wheeled dog cart. Mr Paxton had special livery for summer and winter as well as Sunday. The brougham was very handy in the war for one of the young RAF men billeted with us: he had a tendency to stay out late with the girls, but Mr Paxton had told him that the house doors would be locked at a certain time, and that was that. So if he was too late to get in, the young man used to sleep in the brougham and come creeping in when he saw Mr Paxton light the fires first thing in the morning.

‘As well as general cleaning I made the beds and did mending and sewing. And when the fruit came in ripe I had these great big trugs of gooseberries and other berries to top and tail. But for much of the time it was quite easy work, really, and we didn’t reckon to be working all the time; for example I was generally up about 7am but there wasn’t much to do in the afternoon when the lady went calling. We had much more work when visitors came, however, and I’d have to look after Mrs Waudby if Edith and Mrs Paxton were out for the day. In the morning I wore a blue check cotton dress and in the afternoon I was smarter, with a black dress and white apron to receive people. We always knew when Mrs Waudby was coming back because one of her dogs – a Kerry Blue terrier – always barked when her carriage was on its way.

‘There was this wonderfully scented magnolia tree, and Mrs Waudby would cut one of its flowers and put it in a wicker basket to take to a friend when visiting. I think the tree must have been there since the house was built, in about 1850; but sadly it died in the frost of 1940.

‘One of the worst upheavals was spring-cleaning, especially with all those pictures and clutter about, and after the sweep had been in to clear the birds’ nests from the bedroom chimneys. It used to take two of us a whole week just to spring-clean the drawing room – we needed a day just to empty it. The carpet had to be taken out onto the lawn where the garden boy beat it; but he couldn’t help bringing bits of lawn back in with it.

‘When we did the spring-cleaning Mrs Waudby would go away with Mrs Paxton to a hotel for a week or so. The curtains were taken down and changed and cleaned several times a year. In spring and summer they’d be white lace tied with green bows, and the gardener would bring in white arum lilies; when autumn came they were changed to a thick, dark red material and the gardener brought in those lovely chrysanths. Mrs Waudby would never take a chair near the fire, and would often sit alone with just one lamplight in that enormous sitting room. Even in the dining room there was just one silver oil lamp in the middle of this huge table, and I often heard the gentlemen cursing because they couldn’t see to carve the game or joint.

‘We kept some things in the cellar because that was the coolest place in the house, but sometimes it flooded and had to be pumped out. One day I went down to fetch the cream jug and there was a great big toad in it; I had to tell Mrs Waudby, but she just smiled.

‘Mrs Waudby never, ever went to the kitchen; I suppose she just trusted us. The only exception was at Christmas when she came in to see the wonderful staff decorations, as she had none of her own. You should have seen the holly among the gleaming copper pans!

‘Mrs Waudby’s old wireless had earphones, and all the wires ran under the carpet. There were three sets of earphones and whoever was there of a Sunday was allowed to listen to the service as long as they didn’t make a noise; though it was difficult not to when taking the earphones out of the box.’

When the war started, Margaret joined the ARP first aid and went to lectures at Woburn Sands. Mr Paxton joined the Home Guard, which Margaret regarded as ‘the biggest joke of all: he always said he was glad he joined because the only way he kept warm was through wearing their overcoat. When the water tanks froze we had to let the kitchen range go out and it was perishing.’

It was during the war that Margaret rook her ‘nicest holidays ever’, when her brother-in-law Bill was stationed at Banff, on the Scottish coast. She went there three times on the ‘puffing Billy’ (steam train), ‘which changed its tune when it got to the top of the hill and went down again. It took twenty-four hours to get there and you couldn’t move in the carriages for khaki.’ That was quite an adventure for Margaret, because before that her annual fortnight’s holiday was usually spent not far away, visiting an aunt at sedate Leamington Spa.

Things were ‘a bit on the tough side’ during the war, when ‘thousands of Wrens were stationed in the area’, as Margaret recalls:

‘We had to eke out most things because of the rationing, but we got by. Most people took on allotments and many shared out their produce. But clothing was very difficult, and you could easily get rid of your allowance in no time at all.

‘One of my worst memories is seeing that terrible red glow in the sky when they blitzed London in 1941. And there was that awful night they bombed Coventry, when the houses shook with all the bombers going over. One old lady I knew said: “They’ve been going over all night. They’ve shook the firmament and I haven’t got a dry thread left in my body.” But at least we didn’t get any bomb damage at Wavendon.’

After some twelve years at The Old Rectory, Margaret spent about a year working at another local house, where her wages increased three-fold and the hours were only 8am to 3pm; she found it ‘a piece of cake’, particularly as it was equipped with more up-to-date appliances. But then she had to go to help with the war effort, and work at a factory on the outskirts of the village* making transistors for the Navy. However, she had liked the new house so much that she still called in there each day on the way to the factory.

[* Zenith’s factory on Cranfield Road, Woburn Sands – Ed.]

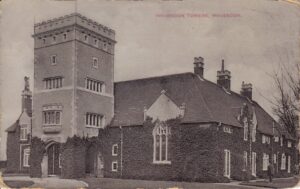

When the war ended Margaret went to The Tower to work as housemaid for the Marler family. ‘They were very agreeable people, estate agents, and I was happy there for eleven years until the family moved away. The only hard work I had to do was endlessly washing pairs of breeches because Major Marler and his elder son used to go out hunting with the North Bucks Beagles so much, often two or three times a week.’

Like so many others, Margaret regarded the ending of the war as a major turning point in the British way of life. ‘Once it was over, everything we held dear disappeared: the women didn’t want to stay at home any more, and that was the beginning of the home life breaking up; and the large staffs went from the big houses’.

Gone were the days when people were content to ‘get round the lamplight in winter to play ludo or snakes and ladders’, a new spirit of independence was prevalent. People generally became financially better off, they were more mobile, and they wanted to venture further afield; and with so many folk looking at life beyond their native haunts it was not surprising that village life and community spirit gradually deteriorated. Margaret’s home patch suffered more than most because it was engulfed by ‘new town’ development: her observations are tinged with considerable sadness:

When the Marlers moved away, that lovely house, The Tower, went to Milton Keynes Corporation for their headquarters*, and there they planned the destruction of thirteen of our beautiful villages, including Milton Keynes itself. It’s criminal that the new town should have taken the name of that delightful little place – there’d been a wonderful Bible with a chain through it in the village since Cromwell’s day. The town should have had a new name. Later The Tower went to an American firm. You have no idea the lovely buildings that have gone, that used to be round that old house.

[* In actual fact, the Marlers left Wavendon Tower in 1955. The Barkers and later the Fernbergs lived there from 1955, before the house was sold to the Milton Keynes Development Corporation in 1967. Ed.]

‘In Wavendon there used to be four pubs: The Red House, The Plough, The Wheatsheaf and also The Leathern Bottle, just over the road where the Ancient Order of Oddfellows used to have a Whit Monday feast in the room attached. The carthorses used to be shod at The Red House, and it was wonderful watching the children help blow the bellows and seeing the sparks fly. We used to love singing that song: “Busy blacksmith, what are you doing at your smithy all day long…” I expect you know it – Handel wrote the tune. Now two of them are private houses. All the old chaps used to have their own special places and seats in the pub. There was much more drunkenness then – it was quite usual to see men staggering about the village, but people used to respect the policeman, and there was never much trouble.

‘But there are not the characters around now, people like Charlie the postman, who wouldn’t finish till gone three on Christmas afternoon and often called whether he had letters or not. He used to see you in the window and shout up things like “You’ve got a postcard, but you won’t like it!” Nothing was sacred then.

‘Another great character was the old verger, who held office for many years. She tolled the bell and tended the lamps, as there was no electricity in the church; if one started to burn low she’d stand on a pew, pull the lamp down and fill it. She often left an oily mess and smell on the pews, so you had to watch where you sat. Also, if anyone misbehaved in church she would tell them to leave. The rector called her “Boss”. He never charged to marry people in church, but would say: “Give Boss half a crown”.

‘There used to be a great many vagrants, mostly begging for hot water for a cup of tea. One old couple used to come round regularly and Mum gave them slices of bread and dripping. How they survived just sleeping in the hedgerows I’ll never know, especially as we used to have such cold winters. The worst I can remember was 1947, when the snow was ever so deep. You couldn’t cross the fields, though the scenery was magnificent. I’d love to see another one like that: it would do everyone good.

‘Tommy Dodd used to sweep the roads on a Saturday and everything was always tidy. Then there was one man from Northampton who used to open his van and there were all these shoes hanging up in rows – talk about a sight! The men used to buy all their heavy boots off him. And right up to the second war a tallyman came round from Stewkley on his bike and sold Mother articles such as tea towels. Another man went round with a van and sold buckets and things. It was always easier to buy at the door when you didn’t have a car or the time to spare.

‘I never drove, but I wished I did. When I left The Tower I went back to the factory where I worked in the war, but things were very different then and you were in good company. It was convenient for me as Mother died in 1959 and I was on my own; also our cottage was deteriorating in condition so I went into a bungalow. Later I moved into this modern brock, owned by Milton Keynes – and so I’ve come back into my former stamping ground because this is where our house used to be. I still love the place and have some good friends – but life can be lonely in a flat, even with people so close; it’s not so social. There’s something very special about living in a cottage; on a nice day you can open the door and sit and watch the world go by. But you can’t do that up all these steps. And you miss the garden. ln the old days you thought nothing of someone coming round with a bushel of peas.’

Although Margaret has many regrets regarding the demise of traditional village life, she has never been one to sit idly by and be overwhelmed by so-called progress. On the contrary, she remain very active in promoting community spirit. She even still rides a bike, ‘but not too far’, despite an accident about twenty-seven years ago in which she broke her hip. She has been closely involved with the church all her life, and after she retired from the factory, aged sixty, she was able to devote even more time to it.

‘It’s a full-time job, really. I was a member of the parochial church council for many years, and now I’m the verger, cleaner and sacristan, which means I look after the altar and sacred vessels. St. Mary’s church dates back to the twelfth century, and we’re very proud of the Grinling Gibbons pulpit, which is said to have been rescued from the Great Fire of London. We only have the one service now: Holy Communion on Sunday. It’s just a matter of form, really – I don’t like these new services – and then only thirty or forty people come. Anyone can take a service here now. In the old days we had 8am Communion, 11am Matins and 6pm Evensong. They never sing those lovely hymns now – the only chance you get to hear them is on TV. I was in the choir for thirty-five years, from 1925 until 1960, and I’ve nearly forgotten how to sing the Te Deum. I sung the solos when I was young, and we used to sing for funerals, too.

‘There was a time when you wouldn’t get a seat at harvest festival evensong if you weren’t there by 5pm. Now it’s all different, but I’ve always stuck to the rule that Sunday should be separate. When we were young even shoes had to be cleaned on Saturday.

‘We also used to have a great many lovely events outside the church; for example there was terrific fun with the village sports and socials. What with “Wings Week” and “Soldiers Week” to raise money for the troops, whist drives, parades and so on, there was something happening almost every night. And the children’s nativity plays were beautiful, too. The British Legion was strong here once, but most of the people who ran it have become too old or have died.’

However, not all has been doom and gloom in Wavendon since the war, and the spark of community hope long nurtured by Margaret Jackson has occasionally been coaxed into flame by celebrities who have adopted the village. John Betjeman came to read poems, famous actors and actresses visited, and The Old Rectory has become one of the homes of the internationally acclaimed musician and composer Johnny Dankworth and his celebrated jazz-singing wife, Cleo Laine. In the very house where Margaret once heard nothing livelier than the ‘awful crackle’ of those first wireless sets, the air became vibrant with innovation and creativity. The Dankworths turned the old stables into a theatre, and when this was extended Princess Margaret and the actress Joyce Grenfell were among the guests at the opening. For that very special occasion Margaret was invited to help out and was delighted to wear her old maid’s frock and apron again, ‘just for a bit of fun’. But she did find it strange to wait at table in a dining room she had known as a kitchen for so long, and she did have to laugh when Princess Margaret’s detective asked if she was local!

Nowadays, when Miss Margaret Jackson talks to local schoolchildren about how village life used to be, she also enthuses about the occasion that Johnny wrote the mass and Cleo sang in church. She is proud to count the Dankworths as friends, and to be such an important link between very different generations.

Margaret could still be found riding her bicycle around the village well into her old age. On her 70th birthday, a party was held where 30 of her old school friends came and she danced with the local Morris troop! Many of her family photos and postcards were used in the book “Wavendon as it was”, produced in 1986 by Richard and Rita Marks.

She eventually moved into the Devon Lodge retirement home in Woburn Sands and passed away in 2010 at the age of 97.

Page last updated Nov.2023.