How Wavendon helped rebuild St Paul’s Cathedral

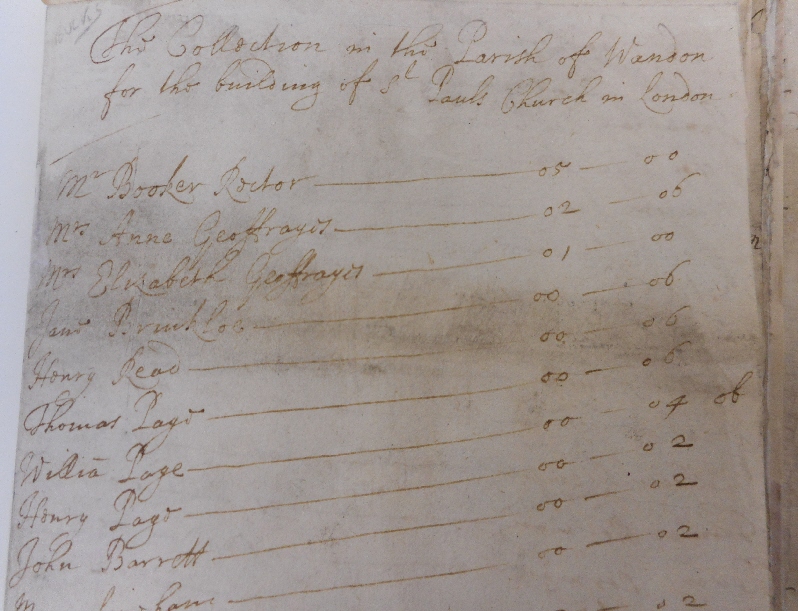

There are not many 340-year-old records from our district that you can go to see and handle, but there are a few that still survive. The London Metropolitan Archives (LMA) holds about 3300 parish subscription lists from 1677-8, showing those who contributed, and how much they gave, to the fund for the rebuilding of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London.

Life in the 17th century countryside, at the far end of Buckinghamshire, was a very remote place. Most people would not have travelled very far at any time in their lives. Newport Pagnell or possibly Bedford would be the limit of most people’s knowledge of ‘big’ places. So discovering these labourers and farm owners had assisted in the rebuilding of one of London’s greatest enduring landmarks was very interesting indeed.

The previous St. Paul’s, which has existed in various forms since 604 A.D., was already ancient and being renovated with the addition of a dome, when the Great Fire of London broke out in 1666. Starting in Pudding Lane, it took two days for the flames to cover the half mile to St. Paul’s, with other fires starting elsewhere due to burning debris blowing in the wind. Before it was extinguished, about 13,200 houses, 87 parish churches, and most of the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall was in ruins.

The wooden scaffolding around St. Paul’s is said to have contributed to the spread of the flames, as did the thousands of books stored in the vaults of the church which had been leased to printers and booksellers. The very fabric of the church and its lead roof contributed to the fire too, as one witness recorded “the melting lead running down the streets in a stream, and the very pavements glowing with fiery redness, so as no horse, nor man, was able to tread on them…”

The destruction put the old St. Paul’s beyond repair. Christopher Wren had already been engaged to modernise the old building before the fire, and had recommended demolishing it and starting again. The fire therefore paved the way for Wren to draw up completely new plans, and incorporate a much larger dome than he had planned to add to the old building. After nine years of various plans being rejected, the design was finally settled on, and building began. Realising the costs would be enormous, a printed appeal brief (an official notice requesting donations) was sent out from King Charles II, in his position as head of the Church of England, to cities, towns, villages and hamlets in all corners of the country, requesting subscriptions to a fund to pay for the works in 1677/8.

The appeal would be read out in church, and a collection taken. The Book of Common Prayer of 1662 even gave instructions as to when in the service any brief was to be read out. Most parishes answered, and we are fortunate that most of Buckinghamshire’s returns are now stored at the LMA.

Some of the names are women, and a few of those are listed as “widdow”. The name Selby appears, of the family which went on to become very important in Wavendon in later years. The rest are a mixture of village names I have seen before, some new ones, and some that I can’t clearly decipher. Mr Wells is possibly the gentleman who set up the Wells Charity by his will in 1713, providing for the poor children of Wavendon. Between them, they raised a total of £1 13s 1/2d to send to London. The Rector and William Goodman, churchwarden, signed off the account. In contrast, Bow Brickhill managed just 12s 9d.

In all, the building of the ‘new’ St. Paul’s took over 30 years to complete. Alas, Charles II did not see it finished. In fact, the building work spanned several monarchs and was only completed in 1708, overseen by Queen Anne. The trickle of shillings and pennies from the shires was never going to be enough to pay for the new cathedral, and so a tax had been placed on transactions of coal within London. One shilling per chaldron (a measure of 52½ long hundredweight) of coal entering London for the following ten years had been instigated in 1667. This was extended in 1670 to all ports and harbours along the Thames Estuary too, and later increased to three shillings, and lengthened by a further three years, with a proportion of the income allocated to St. Paul’s. It is somewhat ironic that whilke flames destroyed the old St. Paul’s, coal for fires helped pay for the new one!

| Name | £. | s. | d. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mr. Booker Rector | 5 | 0 | |

| Mrs Anne Geoffrayes | 2 | 6 | |

| Mrs Elizabeth Geoffrayes | 1 | 0 | |

| James Brinkloe | 0 | 6 | |

| Henry Read | 0 | 6 | |

| Thomas Page | 0 | 6 | |

| William Page | 0 | ½ | |

| Henry Page | 0 | 2 | |

| John Barrett | 0 | 2 | |

| Mary Lineham | 0 | 2 | |

| John Loach | 0 | 2 | |

| Thomas Smith | 0 | 2 | |

| Widdow Norris | 0 | 2 | |

| William Loach | 0 | 2 | |

| Hannah Abnell | 0 | 2 | |

| Richard Lyster | 0 | 2 | |

| Elizabeth Roobart | 0 | 2 | |

| Ruth Norris | 0 | 2 | |

| Sarah Quaint | 0 | 2 | |

| John Pangborne | 0 | 2 | |

| Richard Pangborne | 0 | 2 | |

| Jonathan Foott | 0 | 2 | |

| John Ratcliffe | 0 | 2 | |

| William Lea | 0 | 2 | |

| Ezekiell Roobart sen. | 0 | 6 | |

| Ezekiell Roobart jun. | 0 | 6 | |

| Elizabeth Roobart sen. | 0 | 6 | |

| Thomas Abnell | 0 | 3 | |

| Jacob Allen | 0 | 4 | |

| William Kempe | 1 | 0 | |

| Thomas Norman | 1 | 0 | |

| Edward Norman | 1 | 0 | |

| Widdow Birdseye | 0 | 2 | |

| Thomas Read | 0 | 2 | |

| Mr Wells | 3 | 0 | |

| Barbara Barton | 0 | 2 | |

| James Fathers [?] | 0 | 2 | |

| John Gattlo [Cattlo?] | 0 | 2 | |

| Robert Golton [Colton?] | 0 | 2 | |

| Thomas Golton [Colton?] | 0 | 2 | |

| Thomas Figson [Tigson?] | 0 | 2 | |

| William Parret | 0 | 4 | |

| Thomas Gregory | 2 | 0 | |

| Mr Parret | 1 | 0 | |

| John Smith | 0 | 2 | |

| Sextus Tomkins | 0 | 2 | |

| Mary & Elizabeth Barret | 0 | 2 | |

| Widdow Barret | 0 | 1 | |

| Robert Charnocke | 0 | 2 | |

| Mr Dogget | 0 | 6 | |

| Edward Tomkins | 0 | 2 | |

| William Fitzhugh | 0 | 3 | |

| Thomas Burton | 0 | ½ | |

| William Browne | 0 | 1 | |

| John Gregory | 0 | 8 | |

| John Burt | 0 | 2 | |

| Mr Selby | 2 | 2 | |

| William Farre | 1 | 0 | |

| Thomas Gebel [Gobol?] | 0 | 6 | |

| Robert Traylo [Fraylo?] | 0 | 3 | |

| Thomas Manning | 0 | 2 | |

| John Collins | 0 | 2 | |

| Robert Tomson | 0 | 2 | |

| William Burrel | 0 | 2 | |

| Valentine Parret | 0 | ½ | |

| Total | £1 | 13s | ½d |

[signed] Adam Booker Rector, William Goodman, Churchwardens.

According to George Lipscomb in his “The History and Antiquities of the County of Buckingham” Adam Booker, A.B. was the minister in Wavendon in 1660, so he had ministered there for a few years. A religious census taken in 1676 showed there were 226 conformists and 18 non-conformists in the parish of Wavendon, out of a population of about 400 (What the other 156 classed themselves as, I can’t imagine…)

In 1904, William Bradbrook published research into the early Wavendon Church Registers, picking out the interesting events and compiling some basic statistics, which has been useful in deciphering the names above. The first Wavendon Register covers 1567 to 1721, but the first 30-odd years had been copied into the book from an earlier register that does not now survive. This copying was done by Revd. William Stone, the minister in 1599, whom Bradbrook points out named his own daughter “Pretious” in 1601!

There are four register books, but there is some overlap between them, as the vicar kept separate lists of events at the Hogstye End Friends Meeting House. Quakers have their own burial customs, and as non-conformists, the vicar would have wanted their records kept separate from his own. The family names Brinkloe and Page are often quoted as Quaker families, but it can be seen they contributed as above. It would seem some families switched between religions over time, and occasionally, a former Quaker is noted as being baptised at the church “of ripe years” (i.e. an adult).

In 1665 is the only mention of plague for Wavendon, when on October 25th “Thomas Pancurst servant to Mr Dogget was buried by his fellow servant R. W. being supposed to dye of the plague.” I would expect those above who are only referred to as “Mr.” with no first name given, to have been a class above the general labourers, and the fact that Mr Dogget had at least two servants seems to bear this out. We were taught at school that it was partly thanks to the Great Fire that the plague was eradicated from London.

Other appeals for funds are recorded in the Registers, but Bradbrook makes no mention of this one. In 1703 there was one for widows and orphans “occasioned by the dreadfull storm”, one in 1704 for “Refugees of ye Principality of Orange”, and a more local one in 1743, after a fire in Stony Stratford.

There is another small connection between Wavendon and St. Paul’s. The woodcarvings of St. Paul’s Quire were carved by Grinling Gibbons, who’s work ranks among the best decorative carving of his time anywhere in Europe. At St. Mary’s in Wavendon, the Pulpit has the pea-pod trademark of Gibbons. It was brought from St. Dunstan’s-in-the-West, London, which was rebuilt in 1831, when Fleet Street was widened.

Page last updated Jan. 2019.