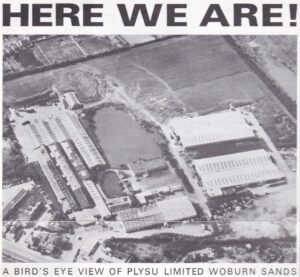

The PLYSU site, Station Road

This page is compiled mainly from notes made on “The Plysu Story” by Jillian Ball (Cambridge Business Publishing, 1991), along with items from my own collection and memories from other local people who were employed by the firm.

A large area of north-west Woburn Sands was once the site of numerous brickworks and other associated industrial businesses. These had mostly closed before the Second World War and still stood empty after it. An enterprising new plastics firm moved their factory from Egham onto the site and it swiftly expanded and grew to employ hundreds of locals in the production of plastic macs, containers and housewares, becoming a household name until it was bought-out by a larger firm in 1999.

The Early Years

Rohan Sturdy worked in audiology before the war and he was drafted into the RAF to help make radio transmissions to airborne pilots clearer. Having helped solve that problem, he was sent to fix the same communications issue in tanks. Whilst doing this for the Ministry of Supply, he met James Summerlin of the War Office. Both were sent to America to work on other new communications systems. What they saw in America convinced them that plastic manufacturing was the future in England after the war.

Together with Gordon Marks and Bill Smith, they decided they had great expertise in high-frequency welding, a process for joining vinyl sheeting together, which had the remarkable (for the time) property of being waterproof. Sturdy was in charge of Administration, Summerlin – Technical, Marks – Sales and Smith – Engineering. The name they chose for their venture was PLYSU, the wartime code-word for the Ministry of Supply. The first headquarters was a house called Warrenbayne in Virginia Water, as it had a large garage and workshop. Jack Cable joined the team and assisted in turning old government surplus transmitters into welding machines. Production was done at an old Lloyds Bank site in Egham, where they made sponge bags, swimming hats and baby pants.

Early problems were caused by the irregular supply of PVC and the quality of what was available. The plasticiser used to make the material supple could also cause issues if not mixed correctly, as the sheeting could become oily or brittle. However, seam-welding was still preferable to stitching, which poked holes in the sheeting to let water in and caused a weak point that could tear easily. As early as 1946, the company had successfully designed a PVC mac that was exhibited at the “Britain Can Make It” show. When lightweight nylon began to impact the profitable mac business, Plysu diversified into protective clothing for atomic, chemical and industrial workers. Their impervious surfaces were easily decontaminated and led to the pressured and ventilated suits still in use today.

In Egham, the firm’s high frequency machines were found to be interfering with local resident’s radio and television sets so new premises had to be found. Summerlin’s wife’s grandfather had just died and left her a small factory building in Woburn Sands, where an agricultural chemical had previously been produced, so production was moved to the 1200 square foot factory in the summer of 1947. Summerlin moved to Woburn Sands and Sturdy to Guise House, in Aspley Guise, where he later became a J.P. and chair of the Parish Council.

Plysu arrived at Woburn Sands with a workforce of about 12, but there was no shortage of willing new employees from around the local villages for the 1s. 6d. an hour wage, responding to adverts such as “RADIO MECHANIC, practical, reqd. prfbly with knowledge of transmitting equipment, accommodation available. Plysu Products Ltd., Woburn Sands” which appeared in a March 1948 copy of the Bedfordshire Times. It was a very popular place to work, with generations of some families working there. The management often helped take staff home at night and allowed them to listen to “Music While You Work” on BBC radio and Sturdy arranged for the verge opposite the factory to be planted with daffodils so the view from the factory windows was pleasant!

A financial crisis at the end of the 1940s led to a new investor insisting on some rapid restructuring. Gordon Marks was let go and several managers went too, although some returned when fortunes picked up. The production of all manner of PVC clothes continued through the 1950’s, along with the industrial protection suits. In 195710,000 macs a week were being made. They had a failed venture to expand into Holland, but more success partnering with a firm in Australia to set up Plastalon. It was from Australia that the idea of moving into housewares and making squeezy mops came from. This involved injection moulding of plastic, which was to become an important part of Plysu’s business.

Homeware Sensation

The ‘Supermaid’ mop proved to be wildly successful. At the Daily Mail Exhibition of 1952, they were selling 300-400 a day, the whole supply of what the factory could produce daily. A new sales force had to be taken on, visiting hardware and corner shops to obtain orders. One such early travelling salesman was Les Dawson, before his comic career took off, who later recounted in his autobiography that he was such a terrible salesman that he was fired! When later presented with a Plysu lavatory brush holder, he quipped “I do not know whether the Hardware Trade made me a comedian or whether I had to be a comedian to sell to the Hardware Trade. All I know if I enjoyed my years with Plysu, although Cliff Atkinson assures me, I was the worst salesman that he has ever employed!”

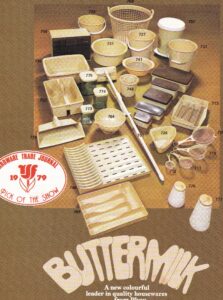

Mops were followed by plastic baskets, strainers, buckets, bowls and dozens of other useful objects which could all be produced in a variety of colours to entice the housewife. Despite buying up more land around the original factory, there wasn’t enough space and an extra site had to be taken in Weathercock Lane and buying up Dudley’s Brick & Tile works land when it became available. They would purchase ex-Army buildings cheaply at auction, go and dismantle them form their old sites, then re-erect them at Woburn Sands.

Newer and heavier moulding machines meant rebuilding the factory floors to hold them and obtaining a supply of water to cool them. One of the old local clay pits was cleared out and allowed to fill with water, providing cheap cooling to the hot machines. They outsourced the provision of lorry transport to deliver their wares, but the trailers were branded in Plysu blue, with their logo on and were once a regular sight on the motorway network, once the M1 opened not far away in 1959.

The next innovation was blow-moulding. This was used to form plastic bottles, of all shapes and sizes, which provided a cheap and quick alternative to traditional glass bottles or metal containers. Plysu were able to come up with their own production method to avoid the closely guarded German and American patents. These could be made with a useful integral handle and were square in shape which helped minimise space for transportation and stacking etc. To finesse the process, they worked on yellow plastic bath duck and other toys, such as a piggy bank that was a tie-in with a film of the time, “Pepe”. There was also a construction toy called Bildit, comprised of plastic axles and spokes to rival Meccano.

Lotta Bottle

When they converted from “women with biros” to a computer in 1966, Selwyn Lloyd, M.P. and former Conservative Chancellor came to do the official opening. The new-fangled machine enabled the sales ledger work and sales analysis to be completed quickly and automatic production of invoices.

It was the bottle business that really took off. In 1968, Plysu sourced machines that could make 800 an hour, rather than the one-at-a-time they previously had. Eventually, they had 20 of these machines, that even reused any scrap plastic from the process. Machines to silk-screen graphics onto the bottles followed, allowing Plysu to personalise orders for customers.

By 1971, the business was able to launch shares on the stock market. The company had made nearly a quarter of a million pounds pre-tax profit, which was announced to the staff over the factory tannoy! A new staff magazine, “Plysu People” was started, which featured the lives and interests of the staff. The 1970s were a volatile time, but Plysu rode out the strikes and three-day weeks by proving it would take even more power to warm up cold machines, so were eventually allowed to run through the period at full capacity. Rohan Sturdy chose to leave in 1974 and went to Bermuda to live.

The 1970s were all about having new products in bright colours in new metric sizes. Plastic fulfilled this need in many houses, certainly most locally had a bright-pink floral laundry basket or storage seat somewhere. Useful ‘sealfresh’ food containers filled fridges everywhere and who could turn down a 13-piece bathroom set, all decorated with the same flowery motif?

The Plysu Sales team went on an annual trip to Spain for their sales conference, possibly where Louis Armstrong’s “Wonderful World” was rearranged thus:

We have Buckets of blue – Dish Drainers too,

Bowls, Mops and Strainers – plus things for the loo.

And we say to ourselves… what a wonderful world.

All these products for the household – are gathered just for you.

Designs are ultra-modern – but they’re very useful too.

They’re made with great care – and tested by three,

then given to housewives – who check u-ti-li-ty.

When all this is done – they’re branded Plysu,

then put on the market in many a hue.

And we say to ourselves… what a colourful world.

Yes – we say to our friends… join our wonderful world.

The workforce now had their own canteen in terrapin buildings (later replaced by a ‘proper’ building) and a social club was formed. An Employee Share Scheme was started. There were Plysu football and cricket teams. Carp were introduced to the lake, along with ducks. In 1986, a purpose-built social club building was erected in the grounds with a bar and Plysu took a corporate box at Silverstone to entertain guests. Many of the staff were volunteer firemen at the station across the road and would have to leave their workstations and dash off when the bells sounded.

A second foray into Holland proved more successful and Plysu Europe was formed by purchasing Phoenix Plastics.. In the early 1980, yet another market was found, that of milk bottles. Supermarkets wanted to offer larger containers than the old standard pint for consumers to buy. They were not only larger, they were also very light compared to glass and fitted well into refrigerator doors and had resealable lids. By 1991, they were making 4m milk bottles a week and the bottles were quite often newer than the milk being put into them! Whilst this meant mountains of scrap plastic, Plysu found a way of reusing plastic in its production of the milk bottles, using between 30-40 tonnes of recycled material a week.

This market meant another 55,000 square foot factory being built on site. Finding the Station Road site unable to expand any further, units were taken nearby at Newport Pagnell and further afield at Littleborough in Lancashire. They also moved the housewares dept. to Kempston in Bedfordshire.

What happened since

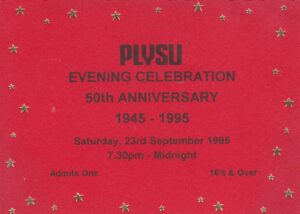

Here Jillian Ball’s book ends. James Summerlin retired from active work in 1995 but became life president of Plysu and stayed local in Aspley Guise. He died in September 1997, exactly 50 years after bringing Plysu to Woburn Sands

Plysu purchased BXL plastics from BP in 1998 which had plants in Leicester. The 1998 Annual Report for the company showed it in good health. Turnover, Profit (before tax) Dividends and Earnings per share had all risen steadily for the last five years. Turnover was £143.7m, gross profit of £37.8m and they had fixed and current assets of over £100m, but it was this success that made them extremely attractive to larger firms…

In October 1999, Plysu bowed to a £94.6m takeover from South African firm Nampak. Shareholders received 196p a share, 61% more than its closing price the day before. Nampak chairman Brian Connellan said there would be no immediate redundancies. Plysu then employed 1,800 workers in the UK while Nampak’s three British sites employed just 300. Nampak was listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange and had interests in nine other southern African countries.

The 5-litre containers production was moved from Woburn Sands in 2000 when Nampak bought Plenmeller in Northumberland, to take advantage of lower production costs.

In the September 2001, Nampak sold the houseware and garden products business, then also sold the large Industrial Containers division to RPC plc of Raunds, a long-time competitor of Plysu, as Nampak wanted to stay solely in food containers. The sale to RPC included the European plants in Holland, Belgium and France, where RPC were also active, and they have since rationalised these facilities, closing some of them. RPC moved all the machinery from Woburn Sands to their plants in Rushden and Plenmeller in 2005-6 and sold the Woburn Sands site to a housing developer. RPC has since been bought by USA giant Berry Plastics Inc.

By January 2002, they decided to close Plysu Recycling, the residual plant at Wolverton that was still in use, as it was not one of its core priorities. Plysu Recycling had a turnover of £2m and processed 2,000 tonnes of used plastic bottles a year, offering a closed-loop recycling solution for local authorities. Used plastic milk bottles were collected and processed at the Milton Keynes materials recycling facility, run by Shanks. The closure showed the problems with plastic recycling in the UK and reiterated the debate over its commercial viability. The Littleborough site closed in 2007 with the loss of 120 jobs. Tom Reid, Nampak’s managing director, said the decision to close the Littleborough plant was ‘most unfortunate’ but had been forced by changes in the dairy industry.

In December 2019, Nampak sold their Nampak Plastics Europe business to Bellcave for an undisclosed amount. André de Ruyter, CEO of Nampak, said: “The sale of NPE is in line with Nampak’s ongoing strategy to sharpen our focus on strategic substrates. We continue to rationalise the portfolio to optimise and improve returns on capital and reinforce our strategic intent.”

The atomic protective suit business had split away from the parent company in 2000 after a management buy-out, so “Plysu Protective Systems” became “Professional Protective Systems”. After a decade, they were purchased by Versar, a US-based global construction and environmental project management company. It was sold again, in 2017, to Groupe Protec SA, a French major environmental technology and testing organisation. PPS still operates in Tilbrook, Milton Keynes.

Plysu housewares and toys still come up regularly on Ebay as collectables. The original Plysu site in Woburn Sands was cleared and a residential estate built in its place. This included many new roads named after the trades and industries that have occupied the site in the past, including a “Plysu Way”. The old Plysu Club was renovated to become the Summerlin Centre, a community hall.

Sources

“Bedfordshire & Luton Topic”, article on Aspley Guise by D. S. Briffett, Dec. 1966

“The Plysu Story”, Jillian Ball, 1991

Plysu – Report and Accounts, 1998

www.thisismoney.co.uk – Plysu bought in £94m deal – 21 Oct 1999 – online

www.Letsrecycle.com – Plysu deals fresh blow to UK plastics recycling industry – 10 Jan 2002 – online

Manchester Evening News – New job shocker as plant closes – 13 Aug 2007 – online

www.britishplastics.co.uk – Nampak Plastics Europe sold to Bellcave – 18 Dec 2019 – online

https://www.ppsgb.com/about-us/history – PPS company history

www.scribd.com Plysu People – Staff magazines – online

Plysu News – Various copies

“Plysu – Gone but Not Forgotten” – Facebook group.

Page last updated August 2020.