The Literary Wiffen Brothers

This article is based on notes compiled mainly from “The Brothers Wiffen: Memoirs and Miscellanies of Jeremiah Wiffen and Benjamin Wiffen” by Samuel Rowles Pattison, Editor, and “Bibliotheca Wiffeniana” by Eduard Boehmer.

John Wiffen, born 1762, was an ironmonger travelling on business, when he stopped at the town of Woburn. He was a well-educated man, who travelled with books in his saddlebags so he could read them whenever he had the chance. Whilst at Woburn, he met Elizabeth Pattison, a mantua maker (dressmaker) who had premises next door to “The George Inn”, later known as “The Bedford Arms”, and now “The Inn at Woburn”. Elizabeth had been brought up in Aspley Guise by a relative of the How family, (who re-enter this story later.) Both were Quakers, and were married soon after.

John moved to Woburn, and Elizabeth’s dressmakers shop was converted to an ironmongers. The passing passenger coaches that travelled the turnpike road would have provided them with a steady stream of business. As many as 120 coaches passed through Woburn every day, many stopping at The George for a break, or to change horses.

A couple of sources report that Elizabeth had some kind of ‘visionary’ experiences, and it is worth recording here an interesting story that appeared in the Bedfordshire Magazine in 1956:

“In last autumn’s Bedfordshire Magazine [Autumn 1955] I published a portrait of Elizabeth Wiffen, mother of the remarkable literary brothers of Woburn. It has now been presented to Luton Museum by Mrs E. S. Boyd Taylor, her great-great-great-granddaughter. Mr Lea, in his article on the Wiffen brothers, mentioned a memoir that Benjamin Wiffen wrote of his mother, but the account has disappeared.

A Dunstable reader and distant relative, Miss E. M. Whitlock, now sends a copy of the original manuscript made by her mother many years ago. It tells of the extraordinary strength of character of this Quaker woman from the time when, as a small child, she was kept sternly to her task of sewing by her aunt, who would say, whenever her childish attention was diverted, “Why do thee look out of the window from thy work? Did thee see a little bird flit by? Can’t a little bird fly by but thee must look at it? Must thee neglect thy work to look at every little bird that flits by the window?”, to the two last years of her life when, preparing for her own death, she made over two hundred articles of clothing for the poor. She married a Woburn ironmonger who died bankrupt when she was 41, and the indomitable woman rescued the business and ran it to keep her family. She had always possessed a strange discernment or intuition which gave her apparent foreknowledge of coming events. Once she and her husband were returning from collecting a debt at Leighton Buzzard when, approaching a steep hill by a wood, she said to her husband, “We shall be stopped here by a robber”, and seizing the reins, whipped the horse into a gallop up the hill. A man rushed out from the wood and tried to catch at the horse’s head, but failed. Turning, she called, “No, no, my friend! Thou art a little too late”, whilst the disappointed footpad yelled curses after them.”

Jeremiah Holmes was their first-born son, born on 30th December 1792, and Benjamin Barron was born in 1794. Another son, John Joyce, died at 14 months in 1802. There were also three sisters, Mary, Sophia and Priscilla.

In 1795, John had to write to the Hogsty End Meeting and offer repentance for having sworn an oath in court at proceedings about a burglary. Quakers were prohibited from swearing oaths on the Bible by their faith.

John Wiffen died in 1802, aged just 40, leaving Elizabeth with six children to bring up. She taught her children the Quaker principles of self-reliance, unswerving honesty and integrity and practical faith, and they always paid credit to her devout spirit and industrious character.

Jeremiah Holmes Wiffen 1792 – 1836

Jeremiah proved to be a great fan of poetry from an early age. He is said to have memorised long poems by heart and had an intuitive perception for the melody and charm of song, which his father had encouraged before his death. After some early schooling in Woburn, and also at schools in Ampthill and Hitchin, he was sent to the Friends Public School at Ackworth near Pontefract in Yorkshire for four years, from the age of ten. Here, as well as poetry, he showed a keen eye for etching, woodcuts (engraving on wood blocks so they could be used to print pictures) and seal making. By selling the woodcuts he made, he obtained some pocket money that he spent in the local bookshops. One particular shop owner steered the young boy away from the more licentious publications in his shop with a bribe of Percy’s “Old English Ballads”, with which Jeremiah delighted his schoolmates by reciting the epic poems to them in their dormitory at night. Once he had completed these, and any other works he could find in print, like Robin Hood etc, he began making up his own stories, and always worked up to a thrilling climax in the story, before leaving his friends with a cliff-hanger ending, to be carried on the next evening!

His schoolwork was said to be excellent, and he was well known for his writing and mathematical ability. Some of his woodcuts made before he left Ackworth at the age of 14 in 1806, were thought to have been used in an edition of Aesops Fables. Whilst here, his own poems began to be accepted by popular magazines of the day, such as the European Magazine, to which he contributed “Stanzas on Winter” in volume 47 in January 1805, and another poem to volume 52 in 1807.

After Ackworth, he was apprenticed to Isaac Payne, a schoolmaster at Epping. The work was long and hard, and left little time for literary pursuits, so he stayed up late into the night to learn foreign languages, writing to his family and friends and memorising more classical poems.

In 1808, he wrote to a old school friend that he had now had work accepted and published by The European Magazine, Minors Pocket Book and also Political Review, and had further work in for consideration with The Monthly Magazine, as well as an account and an engraving of Broxbourne Church in with the Gentleman’s Magazine. Not bad for a 16 year old.

When he reached 19, he had had enough of the harsh work routine, so he left Epping and returned to Woburn. Here, he set up his own school for the sons of local Friends at no.8 Leighton Street. He also continued his own education far into the night, learning Latin, Greek, Hebrew, French, Italian, Spanish and Welsh. He also took an interest in song, and set several of his poems to music.

He joined together with two friends, James Baldwin Brown and the Rev. Thomas Raffles, to publish a book entitled “Poems by Three Friends” in 1812, which was met with very favourable reviews.

Moving back to Woburn allowed Jeremiah to explore the local woodland around Woburn and Aspley Guise. He loved to wander the woods, drawing delicate pencil sketches of nature, or sit reading the latest poems to his sisters and their friends. However, he was happiest when sitting alone, composing lines on what he saw and felt in the tranquil woods.

His next published work was in 1819, “Aonian Hours and other Poems”, in which the principle poem was “Aspley Wood”, with 109 verses. This was followed the next year by another volume of poetry, “Julia Alpinula, with The Captive of Stamboul and Other Poems”, which included “The Russell”, as well as some shorter pieces and sonnets. The subject of “Julia Alpinula,” came from the third Canto of Byron’s ‘Don Juan’. Among the other poems is a “Sonnet Addressed to Wordsworth” which opens, “With thee, divine Philosopher, I gazed; Upon the mighty hills at dying day.”

Around this time, Jeremiah’s sister, Priscilla (Zillah) Maden Wiffen, met and married Alaric Alexander Watts, the poet, who was then also the editor of The New Monthly Magazine. They had a child, Alaric Alfred Watts (1825 – 1901). Zillah also published and wrote for newspapers and magazines like The New Year’s Gift and Juvenile Souvenir (1829-36) until she past away in 1873, nine years after her husband. Sophie, who had also attended Ackworth, was now engaged as a seamstress in Woburn, and Mary was a needlewoman, according to the household bills at Woburn Abbey. Jeremiah took an extended tour of the Lake District with his brother Benjamin, and their illustrator friend Louis Parez, in 1819. The landscape they saw and the hills they climbed also provided him with much inspiration. They visited Robert Southey, (1774 – 1843) who was another poet of the Romantic school, one of the so-called “Lake Poets”, and Poet Laureate from 1813 to 1843. Southey knew the Duke of Bedford and had visited Woburn Abbey. Jeremiah was much taken with this meeting, and later wrote a poem about Southey’s daughters, a picture of whom he had seen on Southey’s mantelpiece. They also went to Rydal Mount, the home of William Wordsworth, and Jeremiah was obviously in awe of the great poet. They talked about the local flora and fauna, and took a tour of his garden, before being invited to come back for tea. They listened as Wordsworth passed comment on the other poets of the day; of whom he admired and whom he felt would disappear into oblivion. Jeremiah recorded in his diary that he thought Wordsworth was rather fonder of talking than listening!

Jeremiah took an extended tour of the Lake District with his brother Benjamin, and their illustrator friend Louis Parez, in 1819. The landscape they saw and the hills they climbed also provided him with much inspiration. They visited Robert Southey, (1774 – 1843) who was another poet of the Romantic school, one of the so-called “Lake Poets”, and Poet Laureate from 1813 to 1843. Southey knew the Duke of Bedford and had visited Woburn Abbey. Jeremiah was much taken with this meeting, and later wrote a poem about Southey’s daughters, a picture of whom he had seen on Southey’s mantelpiece. They also went to Rydal Mount, the home of William Wordsworth, and Jeremiah was obviously in awe of the great poet. They talked about the local flora and fauna, and took a tour of his garden, before being invited to come back for tea. They listened as Wordsworth passed comment on the other poets of the day; of whom he admired and whom he felt would disappear into oblivion. Jeremiah recorded in his diary that he thought Wordsworth was rather fonder of talking than listening!

They went out and watched the sun set over the valley scene before them, taking in the view of Ambleside and Windermere Lake, a vision that Jeremiah recalled as the finest summer vision he had ever beheld. Later, they walked together to Ambleside, and disagreed over the poet Ossian, Wordsworth denouncing his work as false and unreal, which caused Jeremiah to question Wordsworth’s taste in his diary. Ossian was allegedly a poet warrior and the narrator of Gaelic stories, some of which were translated by James Macpherson, but the literary world argued about their provenance for many years. Wordsworth became Poet Laureate on the death of Southey in 1843 until his own demise in 1850. By the end of their trip, they had travelled 785 miles, walking 307 of them.

Jeremiah entered a new stage of his life when John Russell, the 6th Duke of Bedford, appointed him as the official Librarian for Woburn Abbey in 1821. John Russell was opposed to many of the conflicts that Britain had involved itself with, along with his son, funded many anti-war publications. This would have meant he possibly had a strong affinity with the Quakers.

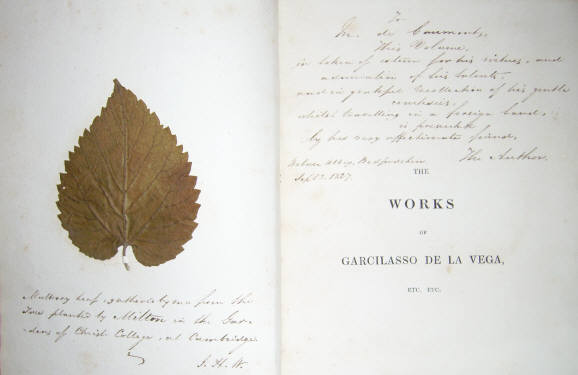

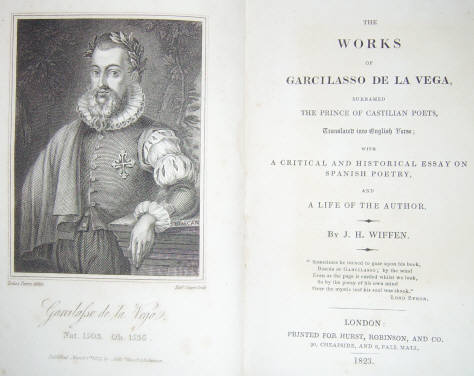

The early European poets had long fascinated Jeremiah, and on the suggestion of his brother Benjamin, he began to translate “Jerusalem Delivered” by Torquato Tasso from Italian into English. This took several years, and at the same time, he also translated the works of Garcilasso de la Vega (b.1503-1536) a Spanish poet and soldier, which was published in 1823, and dedicated to John, Duke of Bedford.

Many years later, his brother Benjamin talked to Dr. Thackeray at Cambridge, and wrote home to his wife of Thackerays recollection of his first meeting Jeremiah in about 1822. Jeremiah had been trying to gain entry to the public library there, but had been refused as they did not know him. Dr. Thackeray vouched for him, and when they refused to allow Jeremiah to borrow 40 books, he allowed him to stay at his house for a week, while he made notes on the volumes. Whilst there, Dr. Thackeray took Jeremiah to see the Mulberry tree planted by Mlton in the gardens of Christ College. He arranged for Jeremiah to be given a cutting of it to take back to the Duke of Bedford. Milton’s mulberry tree was planted in 1608, the year of Milton’s birth and was named in his honour, as a former student of the college. It is said that he sat under it when he composed Lycidas. (The tree that stands today in the garden is probably an offset of the original, having grown up from the roots as the old trunk died off.) Jeremiah was obviously very impressed with this, and used at least one leaf to dedicate the book to a friend:

Jeremiah also used the occasion to write a poem in 1824:

On Planting a Slip from Milton’s Mulberry Tree, in the Grounds of Woburn Abbey, Presented by Dr. Thackeray, of Cambridge.

The mulberry mourns in its changed hue, the doom

Of love-lamented Thisbe, and the fond

Stripling she ruined; but a charm beyond

That elder story, henceforth shall allume

The song which chaunts its praise; for in the bloom

Of life, celestial Milton from the throng

Of verdurous sylvans, chose it to prolong

His memory here. He slumbers in the tomb,

But this is yet unfading. Chose he not

Thy frame, dark tree, to shadow forth his woe

For those diviner lovers whom his verse

Wept for, cast forth from Eden? The dire blot

Makes us yet weep; but all sweet leaves below

And holiest blossoms sanctify his hearse.

Jeremiah had already had advance subscriptions for 160 copies of his“Jerusalem Delivered”, and was meeting and corresponding with many of the leading literati of London, who were all impressed with the work he had done. However, on the eve of completion, a fire at the printers works consumed the labour of years in an hour. But Jeremiah recovered from this setback, and the book was published in 1824, and dedicated to Georgina, Duchess of Bedford.

Jeremiahs book was named “Jerusalem Delivered: an Epic Poem in Twenty Cantos: Translated Into English Spenserian Verse from the Italian of Tasso: Together with a Life of the Author, Interspersed with Translations of His Verses to the Princess Leonora of Este”. It was illustrated by an engraved portrait of Tasso, after a drawing by Louis Parez, and in the list of subscribers were Scott, Thomas Lawrence, Ugo Foscolo, Samuel Rogers, William Roscoe, Thomas Campbell, Thomas Moore, William Sotheby, Alaric Watts, J. G. Lockhart, David Wilkie, John Flaxman, W. L. Bowles, T. F. Dibdin and B. Barton, who some of the owners of the finest country house libraries of the time and also noted bibliophiles. There were two wood engraved vignette illustrations in the text by Williams, also 20 wood engraved canto headings by Williams and Thomson after Henry Corbould and George Hayter (some with tissue guards), and a facsimile of Tasso’s hand-writing.

Torquato Tasso (1544-1595) is often referred to as the greatest Italian poet of the late Renaissance, “La Gerusalemme Liberata” was his most famous work, written in 1575. Its hero was the leader of the first Crusade, Godfrey of Bouillon, who captured the Holy City. In the 1570s Tasso developed a persecution mania that led to legends about the restless, half-mad, and misunderstood author. He died a few days before he was due to be crowned as the king of poets by the Pope. Tasso remained one of the most widely read poets by educated Europeans until the beginning of the 19th century.

His work at the Abbey is mentioned in his letters, and he recalls finding an early manuscript Chronicle of England, apparently written by the monks of the Abbey. The Duke asked him to read it – no easy matter I imagine to translate these early writings. I do not know if it has survived.

He sat for a portrait by George Hayter in 1824, (and again for William Brockedon in 1830), but suffered an attack of rheumatic fever in 1825, and went to recuperate in Brighton. His letters of this period show he was quite depressed at having finished translating Tasso, which he felt left him with no purpose. The great love of his life had married another, and then died, but he had found happiness with Mary Whitehead, whom he married in November 1828 at the Friends Meeting House in Leeds, and had used her as a model for Ida in some of Tasso’s work. By 1830, they were living at Froxfield, just east of Woburn Park, with their first daughter, Ida Margaret, who was born the year before. Two further daughters, Mary Isaline and Hannah Holinshed, completed their family.

While his Tasso translation was delayed by the printers fire, Jeremiah had began work on a history of the Russell family. The research on this, which took him to Normandy for four months, took eight years in total, and the resultant book was the most detailed family history he could compile. It was published in 1833, as “The Historical Memoirs of the House of Russell”. The Senate House Library, at the University of London, holds 25 pages of manuscript notes of the book, but it breaks off at about 1230AD. A number of engravings are inserted, including seven taken from the large paper edition of the book.

Jeremiah had been feeling short of breath, and complained to his brother that he had difficulty in breathing. There was no other outward sign that he was unwell, but he died suddenly at home during the night of May 2nd 1836, aged 43. His wife had sent for a doctor, but he died before they arrived.

A friend recalled how the entire length of the road through Woburn Park, through the town of Woburn itself, and down to the Friends Meeting House at Woburn Sands was thronged with people who had come from far and near to pay their respects. Jeremiah Holmes Wiffen was laid to rest in the burial ground behind the Meeting House. The Times, of May 10th 1836 reported:

“We regret to perceive in the Literary Gazette the announcement of the death of Mr J. H. Wiffen, the historian of the house of Russell, and author of other works of considerable merit. On Monday night Mr Wiffen retired to rest at Woburn Abbey, where he held the situation of Librarian to the Duke of Bedford, and whence his literary productions emanated, in perfect health and contentment, at his usual hour, and in a few minutes after he was a corpse. He belonged to the Society of Friends, and has left a widow and three children to deplore his premature and melancholy decease. His estimable qualities as a private individual endeared him to all who knew him.”

As well as the publications already described, he also contributed poems and sonnets to ‘Elegiac Lines‘ (1818) with his brother Benjamin, and wrote a number of other volumes of poetry: ‘Verses written on the Alameda at Ampthill Park’ (1827), ‘Appeal for the injured African’ (1833), and ‘Verses written in the portico of the temple of liberty at Woburn Abbey, on placing before it the statues of Locke and Erskine, in the summer of 1835‘ (1836). His wife Mary died in 1849, aged 58.

He also contributed poems to the following literary annuals:

Forget Me Not [which was published 1823 – 47, and 1856]

’To the Rose’, in the 1824 annual, on page 309

’Letrilla’ (from the Spanish), 1825, 155 and 266

’To a Lady’, 1825, 382

’Romance’ (from the Spanish of Góngora), 1826, 102.

Friendship’s Offering [1824 – 44]

’Ode to the Turtle’, 1826, 140

’From the Spanish of Francisco de la Torre’, 1826, 286

’Welsh Melody’, 1826, 353

’Ballad’ (from the Spanish of Góngora), 1827, 97

’Letrilla’ (from the Spanish of Góngora), 1827, 134

’To Melancholy’, 1839, 360.

Literary Souvenir [1825 – 35]

’To a Lady’, 1825, 176

’Palmyra’, 1825, 183

’Stanzas for Music’, 1825, 235

’The Luck of Eden Hall’, 1826, 26

’Stanzas for Music’, 1826, 178

’Stanzas for Music’, 1826, 218.

Amulet [1826 – 36]

’Ode to the Ruins of Italica’ (from the Spanish of Rioja), 1827, 262.

Bijou [1828 – 30]

’Milton dictating to his Daughters’, 1830, 146.

Winter’s Wreath [1828 – 32]

’To the Cuckoo’, 1829, 359

’To Maeswyn’ (from the Welsh of Llywarch Hen), 1829, 387

’Song of the Beautiful Persian’, 1830, 52

’To a new Visitant’, 1831, 171

’A Vision of Barden Tower’, 1832, 284.

Pledge of Friendship [1826 – 28]

’On Parting with my Mother’ (translated from Torentio Tasso), 1827, 149.

Aurora Borealis [1833; issued as “Friend’s Annual,” 1834]

’Appeal for the Injured African’, 1833, 24

’Lines written in an Album’, 1833, 166.

New Year’s Gift [1829 – 36]

’The Early Wed and Early Dead: An Historical Tale’, 1829, 33

’The Children in the Wood’, 1829, 68.

Also possibly another in:

Amulet [1826 – 36]

’The Last of the Constantines’, 1826, 95.

ASPLEY WOOD (1819) [The first five verses of 109]

The breath of Spring is on thee, Aspley Wood!

Each shoot of thine is vigorous, from the green,

Low-drooping larch, and full unfolded bud

Of sycamore, and beech, majestic queen!

With her tiara on, which crowns the scene

With beauty,—to the stern oak, on whose rind

The warmest suns and sweetest showers have been,

And soft voice of the fond Favonian wind;—

His thousand lingering leaves reluctantly unbind.

But of all other trees, a clustering crowd

Bow their young tops rejoicingly, to meet

The breeze, which yet not murmurs overloud,

But wastes on Nature’s cheek its kisses sweet,

To woo her from dark winter;—the wild bleat

Of innocent lambs is on the passing gale,

Blending with pastoral bells, and at my feet,

From yon warm wood the stockdove’s plaintive wail

Wins to the curious ear o’er the subjected vale.

O Nature! woods, winds, music, vallies, hills,

And gushing brooks,—in you there is a voice

Of potency, an utterance which instils

Light, life, and freshness, bidding Man rejoice

As with a spirit’s transport: from the noise,

The hum of busy towns, to you I fly;

Ye were my earliest nurses, my first choice,

Let me not idly hope nor vainly sigh;

Whisper once more of peace—joys—years long vanished by!

To you I fled in childhood, and arrayed

Your beauty in a robe of magic power;

Ye made me what I am and shall be, made

My being stretch beyond the shadowy hour

Of narrow life,—ye granted me a dower

Of thoughts and living pictures, such as stir

In the eye’s apple; to the breathing bower,

Here, where bright chesnut weds the towering fir,

Recal fair Wisdom back that I may dwell with her.

Visions on visions! how the moving throng,

These bright remembrances on fancy press

Buried enjoyments as I pass! the song

Sung in the hushed vale’s verdant loneliness,—

The storm—the sun—the rainbow—the vain guess

Of notes heard in the distance,—the advance

Of bells upon the wind,—the loveliness

Of flowers, unwithering in the sun’s hot glance,

The thousand hopes that high in Youth’s brisk pulses dance:

Poetry:

From “The Brothers Wiffen” (1880)

Ode to Meditation (1807)

Lines Written in Epping Forest (1807)

From “Poems by three friends” (1813) by Wiffen, Brown and Raffles. I have not been able to establish who wrote which poems in this book To Thomas Campbell, Esq.

Introduction.

Hymn to the Deity.

Henry’s Harp; A Tribute to the Memory of Henry Kirke White.

Fragment.

An Orphan Girl’s Reflections.

Ode to Meditation.

Epitaph.

To a Friend, on his Expressing a Wish for the Possession of Poetical Talent.

Impromptu to Marianne.

Address to the Sun: Imitated From Ossian.

Hymn for an Orphan.

The Balm for Every Wound.

Epitaph.

Inscription in an Arbour.

Hymn, For a Day of Public Humiliation

Imitated from Ossian

Translated: Horace, 65 – 8BC; Horace, Book 1. Ode 1. To Mecaenas.

The Bird of Yarrow; A Tribute to the Memory of William Hamilton, Author of the beautiful Song, after the ancient Scotish Manner, entitled “The Braes of Yarrow”.

Lines, addressed to…

Contemplative Stanzas.

God Unsearchable.

Epitaph.

Ossian’s Address to Congal.

Translated: Horace, 65 – 8BC; Horace, Book 1. Ode IV. To Sextius.

Farewell to the Maid of Mallwydd.

The Highlander.

Ode to the Memory of Collins.

Malvina.

Description of a Stormy Night, Imitated from Ossian.

Translated: Horace, 65 – 8BC; Horace, Book 1. Ode XIV. To the Republic.

Lines to a Friend in Sickness.

Imitated from Ossian.

To My Lyre.

Epistle to Walter Scott, Esq.

Description of a Battle, From Ossian

The Tulip and the Rose, Addressed to E….

Psalm VIII. Paraphrased

Ossian’s Address to the Sun, Imitated

To….

Ode on Human Life.

Translated: Horace, 65 – 8BC; Horace, Book II. Ode III. To Delius.

Lines Written in a Lady’s Album

Ode from Osian

To Mary

Descriptive Sonnet, written on the Summit of Cader Idris, North Wales

Lines Written in the Hermitage, at The Fox under The Hill, Burford Bridge, Near Dorking, Surrey.

To Anna.

Imitated from Ossian

Lines Written on Leaving.

To Mary.

Lines, Written in a Copy of “The Pleasures of Hope”, Presented to a Young Lady.

The Joy of Grief

The Harp of Love

Conclusion.

Reprinted in “The Brothers Wiffen” (1880) To Miss M. Raffles Oetat III (1817)

To a Lady with a Sprig of Cypress (1818)

From “Aonian Hours; and Other Poems” (1819)

Aspley Wood.

To ——.

To ——.

Propertius; Book III. Elegy X. To Leuce.

To a Lady Netting.

Parting.

To ——.

The Vase of Lilies.

Stanzas.

The Last but One.

Lines on Howard. [Originally published in the “Life of Howard,” by J. B. Brown, Esq. of the Inner Temple.]

From “Julia Alpinula [etc.]” (1820)

To Alaric A. Watts, Esq.

Julia Alpinula.

The Captive of Stamboul.

The Russell.

Lines Written on a Blank Leaf of the “Pleasures Of Hope.”

Lines Written Beneath a Miniature in the Possession of a Friend.

The Legend of the Statue.

To— With a Seal Bearing the Inscription “Con Te Sono.”

After the Spanish.

“Et longum, formose, vale! vale! inquit Iola.”—Virgil.

I took the Harp.

Written in an Album.

Sonnet to W. Wordsworth, Esq.

To—.

Taliessin.

The Cascade on Raven Crag, near Lake Coniston.

Newstead Abbey.

From “The Brothers Wiffen” (1880)

On receiving an Autograph Poem by Henry Kirke White, from his Sister (1822)

To Dr Joseph Thackeray (undated)

On Planting a slip from Milton’s Mulberry Tree in the Gardens at Woburn Abbey (1824)[See main Wiffen page for this poem]

To My Friends (1824)

The Inquisition of the Year [An introductory poem for the 12th vol. of “Times Telescope” (1824)

To Mary and Hannah, on leaving their Garden (undated)

Farewell (1824)

To a Lady in Affliction, with a Rose (1825)

Ode (1825)

Line written in an Album (undated)

The Echo of Antiquity, Lines Written in York Minister (1825)

I Need No More (1825)

Sonnet to M. D. D’Isigny (1826)

To The Rose [From the Spanish of Don Francisco De Rioja] (undated)

To The Jessamine [From the Spanish of Gongora] (undated)

On a Ring [Sent to J. Wiffen as a Memento of his friend I D Strutt who died abroard] (undated)

Sensations under the influence of Nitrous Oxide Described [Written immediately after inhaling it] (undated)

To Ida (undated)

Evening Reverie (undated)

To Ida (undated)

The Oaken Bough Pt. 1 [Emblem of Duke of Bedford in election] (1826)

The Oaken Bough Pt. 2 [Election dinner at Bedford] (1831)

On a leaf from Milton’s Mulberry Tree, Cambridge (1826)

To the Cuckoo in the Vale of Cuawg [From the Welsgh of Llywarch Hen] (1826)

To Maenwyn [From the Welsgh of Llywarch Hen] (1826)

I Crossed in its Beauty thy Dee’s Druid Water [Set to music by John Parry] (undated)

Sonnet to George Hayter Esq. MA. SL &c (1826)

The Abbots Oak (undated)

To Samuel Fox (1829)

To My Wife (1828)

Verses on the Alameda at Ampthill Park (undated)

The Luck of Edenhall (undated)

The Prophecy of Barden Tower (undated)

The Raid of the Reidswire (undated)

Others Lines Written in the Portico of The Temple Of Liberty (1836)

Unknown.

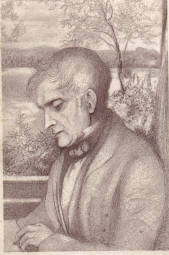

Benjamin Barron Wiffen 1794 – 1867

Benjamin Barron Wiffen was born 28th October, 1794, and followed his older brother Jeremiah to Ackworth School, leaving two years after him, as did Sophia, their sister. Benjamin returned home and assisted his widowed mother and sisters with the family ironmongery business in Woburn, which was still next door to the Bedford Arms, and here he remained until he was 43. He was well known as being particularly fastidious about his business and the public offices he kept, accepting no excuses and expecting everything to be properly authorised and ordered at all times.

In Aspley Guise, there was another large family who were also Quakers; the How family. Richard How Snr. had put together a fine library of more than 5000 books. He died in 1800, leaving the collection to his son Richard Thomas How, a shy man who disliked publicity, but his literary interests attracted Benjamin, who’s own literary heritage meant the two became firm friends.

Benjamin retired from business in 1838 on health grounds, and he, his mother and his sisters moved to a house “The Haven”, at the very end of Mount Pleasant, in Aspley Guise. His mother died three years later. Their shop continued in the ironmongery business until it was demolished after the First World War, and on its site now stands the Woburn War Memorial.

Benjamin had wanted to commit his full attention to his business, so he had abandoned his early poetic interests, and was said to have burnt all his early verse.

About this time, a Spanish nobleman, Luis de Usoz y Rio heard that Jeremiah Wiffen had translated one of his favourite authors, Garcilasso de la Vega, into English, and was most keen to track him down. He came to England, where he learnt that Jeremiah had passed away, but a Quaker in London contacted Benjamin and convinced him to meet with Luis. After discussing his brother’s work, they had a frank discussion about religious liberty, and as Luis had also studied Quaker ideals, they found they agreed on the same points. This started a lifelong friendship between the two.

In 1839, Benjamin travelled to Spain with George William Alexander, treasurer of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, to campaign on the abolishment of the slave trade, a cause he was very much involved in. The country, its people and the scenery enthralled him. He was moved to return to poetry when he got back, and “The Warder of the Pyrenees” was published in ‘Finden’s Tableaux’, a publication edited by his sister. Don Luis then brought his wife to visit the Wiffen family at home in Aspley Guise in 1841, and whilst here, the two literary men decided to rescue the works of the Spanish reformers from obscurity .

From that moment, Benjamin’s life was taken over by the work of sourcing and translating the works of the early Spanish reformation writers. After Luis had returned home, Benjamin found an unknown work by Juan de Nicholas Sacharles, and sent it to Luis. He was so grateful to have the book, he provided money for Benjamin to seek out other such books that had escaped the purges in Spain. Some had been lodged in European archives before the Inquisition, and refugees had taken some of them out of the country.

Once his interest in Spanish literature was kindled, Benjamin was consumed with the work of locating, translating, editing or superintending the printing of a number of volumes of Spanish literature, in conjunction with Luis. Luis had to be careful about this work, as although the Inquisition was long past, the authorities of Catholic Spain were not happy with anyone promoting the ‘heretical’ works that challenged their religious beliefs. Indeed, Spanish spies were sent to Benjamin’s home to try and discover the identity of his Spanish publishing partner, and the printing of the books in Spain was done so secretly, that some thought Benjamin was printing them himself in Aspley Guise.

Some of the letters between Benjamin and Luis survive at the Wadham College Library, Oxford, although it is not known how they got there. Luis is apologetic over his knowledge of English, and sometimes wrote in French, but he makes frequent references to the danger of letters from Benjamin falling into the wrong hands. Luis’ own father was Catholic, and objected to the Quaker cause, going as far as stopping Luis’ brother Santiago from visiting England, so all Benjamin’s correspondence had to be sent via safe houses. If Spanish Customs in Madrid impounded books, Luis doubted that they would be released. He asked that mail be sent by the new steamboats for speed, but sometimes used a military contact in Gibraltar to transport the letters and the books that they exchanged.

Luis attempted to find contacts in Spain for the Anti-Slavery Society campaign, but made little headway. They were also involved in the Society for Peace in England, and discussed Benjamin moving to Spain to benefit his health. As well as the important campaigning matters and their publishing work, Luis also asked for the recipe for English Plum Pudding!

Richard How died in 1835, and lodged at Bedfordshire and Luton Archives [Z813/1] is Benjamins hand written memorial to him, penned in 1840. In fine copperplate handwriting, the book is titled “Memorial of Richard Thomas How addressed to those who knew him not”. It is dedicated to Richard Edward White [whose own diary features in some research on another part of this site] “…in the hope that his children’s children will preserve the memory of one of their ancestors in order to imitate his virtues.” It is over 300 pages long, describing not only Richard How, but his house and gardens in Aspley Guise, the Hogsty End Meeting House and the local Quaker community. Benjamin was still very actively involved in the Quaker community himself, looking after the records of the Meeting House until the Registration Act of 1837.

Some of Benjamin’s experiences as a book-hunter are left in his memoirs. He used every lead that came to his attention on Spanish 16th century literature, and contacted museums, book collectors and archives throughout Europe in his quest. Sometimes he bought book collections at auction to obtain a single book, sometimes they were found for a few shillings in bookshops where the owners still considered them as ‘bad’ books, being anti-papal. One particularly interesting book he found in Richard How’s library near his home in Aspley Guise. He spent years courting some people to elicit books he knew they had, just to be allowed to transcribe them and forward translated copies to Luis in Spain. Some were in English, some Spanish, others in Latin. Some books could only be found translated into other European languages, as all copies of the original Spanish versions had been destroyed in the Inquisition.

Together, they issued a series of 20 books, known as the Reformistas Antiguos Espanoles (Early Spanish Reformers). Those books found, translated and reprinted were:

1. “Carrascon” by Fernando de Texeda, 1847

2. “Epistola Consolatoria” by Juan Perez de Pineda, 1848

3. “Imajen del Antecristo” & “Carta a Don Felipe II” by Juan Perez, 1849

4. “Dos Dialogues” by Juan de Valdes, 1850

5. “De Montes” ??

6. “Dos Tratados” by Zipriano de Valera, 1851

7. “Breve Tratado de Doctrina” by Juan Perez, 1852

8. “El Espanol Reformado” by Juan de Nicholas Sacharles, 1854

9. “CX Considerationes” by Juan de Valdes, 1855

10. “Commentary on the First of the Corinthians” by Juan de Valdes, 1856

11. “Commentary on the Romans” by Juan de Valdes, 1856

12. “Las Dos Informaziones” by Franzisco de Enzinas, 1857

13. “Authors Letters” ?? 1857

14. “Calvins Institutes” by Zipiano de Valera, 1858

15. “Alfabeto Christiano” by Juan de Valdes, 1861

16. “CX Considerationes” (1558 M.S. version) by Juan de Valdes

17. “CX Considerationes” (Improved Spanish version) by Juan de Valdes, 1863

18. “The Breve Sumario” by Juan Perez, 1862

19. “Suma, Sermon, Catezismo and Confesion” by Dr Constantino Ponze de la Fuente, 1863

20. “Letters to Ochino, Enzinas and Calvin” by Juan Diaz, 1865

Outside the main series of books, Benjamin also assisted with some others, including:

Cenni Biografici sui Fratelli Giovanni e Alfonso de Valdesso, 1861

Origines de la Lengua Espanola” Valdes, 1861

Luis died a few months after publishing the 20th book of the series. They had sought out and made available some of the rarest religious writing in Europe, spending 25 years in the pursuit. Benjamin felt the loss of Luis greatly, but continued to publish further works of the same type, republishing the “CX Considerationes” again, with added work on the life and writings of Juan de Valdes in 1865.

Soon after this, his own health began to decline, and after being very ill in the winter of 1866, he died at the end of March 1867, aged 73. The notice recording his passing in the Quakers Annual Monitor said:

“It seems to have been his wish that he might slip away unobserved, and this was the case. He was gone before most of his relatives and friends knew that he was ill. He does not appear to have spoken much during his last illness; but what little was said implied his firm trust in the atoning sacrifice of our Lord and Saviour; and we believe that he has entered upon an eternal rest in Jesus. He peacefully departed about six o’clock, on the evening of second day,[Monday] the 18th of 3rd month, 1867”

His funeral took place at the Friends Burial Ground at Woburn Sands, six days later. His sister Sophia had pre-deceased him in 1864.

After Benjamin’s death, his collected notes on each of the authors he had researched were used by Ed. Boehmer, D.D., Ph.D., the Ordinary Professor of the Romance Languages to the University of Strasburg, to produce “Bibliotheca Wiffeniana, – Spanish Reformers of two Centuries, from 1520, their lives and writings, according to the late Benjamin B. Wiffen’s plan, and with the use of his materials”. This was published in three volumes between 1874 – 1904, and it also included a memoir of Benjamin by Isaline Wiffen, Jeremiah’s daughter.

In 1869, John T Betts republished “The Confession of a Sinner”, by Ponce de la Fuente, Constantino, which also contained some biographical work by Benjamin.

Page last updated Jan. 2019.