The Centenary of Woburn Sands and its Parish Church, by Michael Meakin, Vicar of Woburn Sands, 1968

The following church history was writen by the incumbant vicar of the time, Rev. Michael Meakin. The original is not illustrated, but I have added pictures from my own collection.

At the end of this page is a copy of the sermon preached by Edward Harold Browne, Lord Bishop of Ely, at the consecration of St. Michaels in 1868.

THE MEETING OF FIVE WAYS

The modern traveller hurries across the Square of Woburn Sands, as he sees a break in the fast moving traffic of the A50, and the cross traffic coming and going to the M1, with the ever-increasing Church Road traffic adding to the confusion. He could pause and look about him, if it were only possible to be transported back a hundred years.

The five ways of the Square would be found the same a hundred years ago. The Swan Hotel with all its changes, has long stood on its present site. It had been the place where horses were changed for the Stagecoach, and from The Swan all the land down to the Railway was farmed. Between The Swan and the Station – Wavendon Halt – are few houses, the fine 18th Century Georgian house to become the Vicarage, and a few smaller houses nearer the Station, but otherwise fields all the way and few of the roads that today lead off it.

Hardwick Road led to Hardwick House, demolished in the nineteen-fifties, but opposite stood the little 17th Century cottage, which for nearly 250 years was the Friends’ Meeting House, pulled down in 1901, and replaced by the present building which today serves as a branch of the County Library.

Next of the ways is the present Church Road, which led on as far as Sandy Lane, by Aspley Heath School (opened on 14th September 1868), where Sandy Lane became the main road, and wound up through the trees to the little group of cottages that formed George Square, and the few cottages here and there where ale could be obtained by the thirsty Fullers Earth workers.

The road to Woburn did not follow its present route through the sand hills, and so the climb over the top was steeper; but doubtless this was the pride of the place – the magnificent wooded land coming to the edge of the little group of houses that formed the hamlet of Hog Sty End.

It was said that the drovers of pigs on the way to Smithfield stied the beasts here. If so, they had a choice between the refreshments provided by The Swan and that of the thatched Firtree Inn, that led to the fifth way – up the hill to Aspley Guise.

Here were most of the residences of the time. Here were such shops as existed, for the old name of Aspley Hill was Cheapside. It would seem that the would-be worshipper might well walk this way to Saint Botolph’s Church, Aspley Guise, as being the nearest Parish Church. But he would then, as now, have explained to him the mysteries of Parish and County boundaries.

The Rector of Wavendon had most of the Hamlet in his parish, and he rode over to take a Service in a room near The Swan Hotel, which also during the week did duty as a School.

Interlude The London Gazette: published by authority. Tuesday, November 5, 1867. By the Queen – a Proclamation. Victoria R. “Whereas Our Parliament stands prorogued to Wednesday the sixth day of November, We, by and with the advice of Our Privy Council, hereby issue Our Royal Proclamation, and publish and declare…”

In the same London Gazette is published the creation of “the District of Woburn Sands.”

While the Church was being built, Disraeli succeeded Lord Derby as Prime Minister, the Dominion of Canada was established and Garibaldi was advancing on Rome.

Before the year 1868 was out, Disraeli had resigned and Mr. Gladstone was in office. Within a short period the Irish Church was disestablished, the Suez Canal was formally opened, France was at war with Prussia, and Charles Dickens was dead.

By then the inhabitants of Woburn Sands were making their way Sunday by Sunday up the hill, along the very rough and quite disgraceful “carriage road” to the new Church of Saint Michael, with its unusual thin pillars in the French Gothic style and its fine commanding view.

HAMLET TO PARISH Situated at the extremities of the two vast dioceses of Oxford and Ely, it is doubtful whether any instigation to create a new parish came from either source. It is now impossible to find who made the first moves, for Deanery meetings make no mention of the growing needs of Hog Sty End. The creating of a new parish out of different parishes in different counties, in different dioceses must have made quite a problem.

Most of Woburn Sands was carved out of the parish of Wavendon, but some of it was from Aspley Guise; and it is difficult not to see in the Rectors of Aspley Guise the initiators of the move to create the new parish.

The Reverend Hay, M. Erskine resigned from being Rector of Aspley Guise, to become first Vicar of Woburn Sands, and his predecessor at Aspley Guise, the Reverend J. Vaux Moore, left the considerable sum of £5,000 to provide an endowment for the new parish on condition that the Duke of Bedford provided Church and Vicarage.

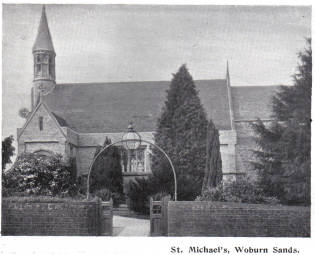

William, 8th Duke of Bedford, chose the field – a fine commanding position in Aspley Heath, even if a little away from most of the houses. The crop of carrots was gathered from the field, and building began, soon to be followed by the planting of the fine conifer trees that stand today. The architect chosen was Henry Clutton, who was a very good architect and, incidentally, a nephew of Cardinal Manning. He was at the same time commissioned to design a new Church for the ducal seat itself, Woburn.

The Church was built and ready for its consecration which took place at 11.30 a.m. on Tuesday, 22nd September, 1868, by the Right Reverend Edward Harold Browne, Lord Bishop of Ely. The Act of Consecration was followed by Morning Prayer and Holy Communion, with a sermon from the Bishop.

Afterwards, the Bishop, those Clergy present, and some others made their way down the hill to luncheon at the invitation of the new incumbent. Mr. Denison, one of the first Churchwardens, had moved out of his Georgian house next to The Swan, and moved down to Hardwick House, so that though the Church was to be a little out of the village, it was provided with a Vicarage at the centre of the community.

Interlude S. Michael’s Ch: Woburn Sands. 5 April 1877. At the annual Vestry Meeting held this day, due and proper notice having been given thereof, there were present:-

W. H. Denison )

Mr. Hudson ) Churchwardens

Mr. Bazley

& the Vicar in the Chair.

The Churchwardens’ accounts for the past year were audited, and, being found correct, were on the proposition of the Vicar, seconded by Mr. Bazley, passed unanimously by the meeting.

The Vicar then submitted to the meeting the Accounts for “the Sick & Poor,” “Organ & Choir Expenses,” “Sunday School,” “Church Fund,” “Incidentals,” which were audited and passed.

The Vicar then nominated W. H. Denison Esqre., for Churchwarden for the ensuing year, and W. H. Denison Esqre., proposed, and Mr. Bazley seconded, that Mr. Thomas Hudson be the Parish Church Warden.

James M. Hamilton,

Chairman.

THE FIRST TWO VICARS

The records that cover the first two Vicars are scant. Hay McDowall Erskine, coming in 1868, was Vicar for six years. With his large beard he must have been an imposing figure. Amongst the many notes that he has left of the events of 1868 is the interesting fact that the population of the new parish was 850 – from Aspley Guise 550, from Wavendon 300, compared with the populations of Aspley Guise 1,437, and of Wavendon 879.

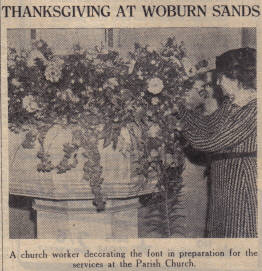

A week after the Consecration was the Feast of Saint Michael – the Patronal Festival – and on that day the Font was used for the first time. The baby, with fine Biblical names, was Michael Eli Job Collins. It was from the same Church that Michael Collins was to be buried on 9th June, 1952, at the age of 83. The first wedding was not until November. Perhaps it lacked a little of the romance of such a first occasion, for it was of a 40 year old widower to a 46 year old widow. In the Wedding Register at pages dated 1872, 16 people had to sign, of those 16, 9 made their mark X and only 7 could write. The first burial in the new Burial Ground was of a child born a week before the Church was consecrated, and of the eight on the first page of the Register, three are under a year old.

In 1875, James Milne Hamilton became Vicar, and remained eight years. He died a dozen years after leaving Woburn Sands, and is buried in our Churchyard. It was in his time that an Organ was built for the Church. It was made by Alfred Monk of Camden Town, London, at a total cost of £300 – a two-manual organ with 18 stops and 768 pipes in all. Mr. Hamilton left Woburn Sands to go to Ridgmont. If it seems strange today to make a move to a Parish so close, it must be remembered that all the livings in the neighbourhood were then in the patronage of the Duke of Bedford.

Interlude Each year Mr. Hamilton published a printed copy of the accounts presented at the Vestry. They were, as we have seen, under five or six headings. Look, for example, at his second Statement. The Account for “the Sick & Poor” makes, perhaps, most interesting reading:- £ s. d.

Relief in Meat & Grocery 5170½

Relief in Money 582

Relief in Milk1 14 0

Relief in Wine & Spirit1 10 3

Cod Liver Oil, etc 10 9½

Books for Sick & Poor 15 6

Prayer Books & Hymn Books 10 10

Wine for Holy Communion (1½ years) 160

Balance 12 6½

“Wine for Holy Communion” seemed to be a problem. In the previous year he had managed to ignore it (thus 1½ years). In the next year it comes in “Incidentals” and it is not until 1879 that it at last appears under “Church Expenses,” together with Sexton £10, and £11 5s. 9d. for a year’s heating and lighting of the Church. But why “Sick & Poor”? (Did any of the same three who made up the Annual Vestry Meeting that year complain?)

EDWARD MOSSE

Edward Mosse must be counted as one of the most notable Vicars of Woburn Sands. He came in 1884, and remained until 1899, when he went to Saint Paul’s, Covent Garden, being killed in an air-raid in the First War. He started a Parish Magazine in 1887, of which bound copies remain up to the end of the Century, so that material is abundant for his time. He must, however, be chiefly remembered for the extension to the Church.

Mr. Hamilton first spoke of “the important question of enlarging the Church.” For the time being, sixty chairs placed up the Centre Aisle met the need for more seats. A project for a second Church, near the Station was for a time considered and then abandoned.

The Church enlargement was agreed upon at a Meeting in the Institute of about 80 members of the Congregation on Tuesday, 19th June, 1888. An eminent architect, Sir Arthur Blomfield, A.R.A., prepared plans. An estimate of £2,500 was given, and the patron of the Living, the Duke of Bedford, promised £1,000 when parishioners had raised another £1,000. The raising of the money began.

There was another major interest at this time – a well prepared-for Parochial Mission in February, 1889. As one of the results of the Mission there was introduced a regular Celebration of the Holy Communion at 8 a.m. every Sunday. Previously this had been only on the 1st and 3rd Sundays of the month, and on the 2nd and 4th Sundays there was the “Holy Communion at the Morning Service” (i.e. at 11 a.m.).

The scheme for enlargement was divided into two parts. First the Chancel was enlarged and a North Transept and Vestries were built, providing 100 extra sittings in the Church. Reconsecration took place on Saturday, 28th September, 1889, by the Bishop of the Diocese. It was the 21st Anniversary of the Dedication of the Church. For the occasion the Choir was equipped for the first time with cassocks and surplices.

But the Vicar looked at the Church and said: “We shall none of us be quite satisfied until we have been able to erect the two Transepts, on the South side of the Church to correspond to that already built on the North. The temporary brick wall is an eyesore.” Alas! 77 years were to pass before anything more was done.

This period is so plentifully supplied with information that it is hard to choose, but much is said as regards numbers by an old receipt found at the bottom of a cupboard, and dated June 28, 1899.

Catering for Sunday School:- 223 Children, 25 Teachers, 15 Band, 6 Bible Class,

269 teas at 5d. each£5121224 Buns at 3 for 2d. 126 £6 47

Interlude In 1888, the Ladies’ Working Party arranged a Sale of Work for the Enlargement Fund. The Sale was held on Wednesday, 1 st August and the two following days. The services of the Village Band in their new uniforms were secured, and a Promenade Concert was arranged for the third day. The Institute was filled with Stalls, and a bridge built to connect it to the Vicarage Garden, which was illuminated by over 700 beautiful coloured glass lamps. Next to the Refreshment Tent in the Vicarage Yard was a shooting gallery and a Doll Show, with two groups, a Wedding and a Christmas Party with furniture and everything complete.

On the morning of the day in June when the meeting was held to arrange the Sale, the Vicar was up in London and over the counter at “Hambley’s, Holborn” he paid 8/6 for “1 Large Fire Balloon” and “1 Large Fire Balloon in the Shape of an Elephant.”

What fun was had by all!

WILLIAM HENRY DENISON

It is inevitable that an account of any Church becomes too easily an account of the various Clergy. This is wrong. The Laity are the Church, and the Clergy members with a particular function. This account of one layman is given to redress the balance a little, and to pay tribute to the Laity who have loved and served their Church so well.

A man in a position of importance can have great influence, and certainly William Henry Denison used his influence aright.

He was born in 1811, and by the time he was 30 he was made Churchwarden of Wavendon. He lived at the present Woburn Sands Vicarage, then in Wavendon Parish. As he saw the houses being built around and the growth of Hog Sty End he became more concerned for the welfare of the people.

Writing at the time of Mr. Denison’s death, the Rev. E. H. Mosse said: “Humanly speaking, Woburn Sands would not have been what it is today if it had not been for Mr. & Mrs. Denison’s untiring zeal and energy in inaugurating the first Church Services, opening and maintaining the first School, and doing all in their power to help and benefit those amongst whom they lived.”

They moved to Hardwick House that their old home might become the Vicarage, and for 21 years Mr. Denison was Churchwarden of the new Parish, doing all in his power for the new Church and Parish. He was very regular at worship.

On Sunday evening, June 8th, 1890, being the First Sunday after Trinity, he was in his place in Church. His white hair and beard contrasted with the sombre black of his clothes. The Service took its course. He sang the Nunc Dimittis. He stood erect and firmly recited the Apostles’ Creed.

He knelt down, for old man though he was, he always knelt. He commended himself to God in the words: “Christ have mercy upon us,” and then before his lips could frame the next words -“Our Father, which art in Heaven ” – he had gone to his Heavenly home.

Before the end of the year the East Window of the Ascension was placed in position as a memorial to Mr. Denison. Now as we kneel in our places in Church and look up to the Altar, we see above it a fitting memorial to one who was indeed in many ways “the father of this Parish.”

Interlude The observance of a Centenary marks something more than the passing of a certain number of years. It marks a change that can only be realised in later years. In the same way, the change from one Century to another marks the end of an old era and the beginning of a new and different order.

In the summer of 1899, Mr. Mosse left. He was succeeded almost immediately by the Reverend Charles Russell Dickinson, coming from work with the Mission to Seamen on the Mersey, and the charge of the Training Ship “Conway.” He settled with his wife at the Vicarage.

In October, the Boer War began. Marconi was experimenting in wireless telegraphy. As 1900 progressed, the war dragged on. The Boxer outbreaks took place in China, and finally, on January 22nd, 1901, Queen Victoria died. But by then, Mr. Dickinson’s brief stay at Woburn Sands was ended. He was a Russell, and he was called to be amongst Russells. The Duke moved him to Woburn.

Now the Twentieth Century was well and truly launched.

DOUGLAS HENRY

The Reverend Douglas Henry came as Vicar in 1901, and just as the memories of Mr. Mosse are of his gentleness and kindness, so Mr. Henry’s good temper and keen sense of humour are remembered. Perhaps he was unpunctual, but certainly “always wearing a top hat” he was not undignified. Fifty years later there were still many who looked back to his memory with affection, but now there are few.

Mr. Mowbray, who was the first layman to read the Lessons regularly in Church, once remarked of Mr. Henry, “If he had been asked to command the British Navy, he would have done it cheerfully.” Nothing was too much for him, for he was always willing to try anything. Because of his bushy eyebrows the children called him “Daddy Eyebrows.”

The bound volumes of the Parish Magazine of Mr. Mosse’s time no longer continue, so that the only written source for the historian is the Minute Book of the Annual Vestry Meeting.

In 1902, “the chief event of the year has been the raising of the money for the stipend of a curate of the parish.” Clergy of today may wonder what there was found in this parish for Vicar and Curate to do, especially as there were a number of Clergy in the Parish at various times, including a Bishop, an Archdeacon, a Canon and a Clerical Headmaster at the Knoll School. A number of names of Curates are mentioned, but the only one to be noted is that of the Reverend John Shelton in 1904. There were complaints about the Church lighting, and the gas from the local gas-works, but the introduction of incandescent lighting was a marked improvement and showed a reduction in the gas bills. Lighting, ventilation and draughts seemed the regular source of complaints, but more than once something was said about “the behaviour of some of the young lads and girls at the back of the Church on Sunday Evenings.” Those who complained then would have no cause to complain now, but perhaps seeing the “young lads and girls” no longer at the back of the Church, they would, if they had known, been a little less righteous in their indignation.

In 1913, Mr. Henry moved to Tavistock, which was also one of the ducal Livings. The Century had progressed. The Edwardian Age was gone. George V was on the Throne. The thoughtful and the well-informed were a little uneasy at the shaping of the 20th Century, but in Woburn Sands all seemed much as it ever had been, as the people waited to welcome the new Vicar, who was no stranger to them. Coming from the Vicarage at Ridgmont back to Woburn Sands was the Reverend John Shelton.

Interlude It should be remembered that at this time the Churchwardens had certain civil, as well as religious functions, so that their election at the Annual Vestry Meeting was by the Ratepayers of the Parish.

At Mr. Henry’s first Vestry Meeting in 1901, there were two nominations for People’s Warden: Mr. Plater and Mr. XYZ. “On a show of hands, Mr. Plater received 44 votes and Mr. XYZ 17.” Thereupon, a Poll was demanded on behalf of Mr. XYZ. Accordingly, a week later, the Vicar with two others sat in the Institute from 1.30 p.m. until 8 p.m. The result of the Poll was Mr. Plater 134, and Mr. XYZ 8.

The name of Mr. XYZ does not often occur until the Meeting on April 5th, 1907. After Mr. Plater had been again nominated as People’s Warden, Mr. XYZ then proposed Mr. Henry Inwood.

“The Vicar asked Mr. XYZ if Mr. Henry Inwood, who was in America, had given his consent to be nominated, but eventually put the two names, and Mr. Plater was elected unanimously. Mr. XYZ demanded a Poll …”

“A Poll was fixed to be held six days later between 12 and 8. The Poll was never held. Mr. Inwood, being in America could not be consulted. His family entirely disclaimed anything to do with the nomination and it was contrary to their wishes. Mr. Inwood was not a member of the Church of England and therefore did not satisfy the New Parishes Act 1843, 6 & 7 Vie., Cap 37. Mr. Inwood, in fact, held a Ticket of Membership of the Wesleyan Methodist Society.

Mr. XYZ did not attend the Vestry Meeting again.

Mr. Henry needed his good temper.

JOHN SHELTON

The Reverend John Shelton came as Vicar of Woburn Sands in the year before the First World War began, and finished in the year after the Second World War ended. It was indeed the spanning of a whole Chapter of remarkable change. Already Woburn Sands was much grown. There were streets of new houses where there had been fields, even though many roads remained unmade. Woburn Sands had now become a civil Parish as well as an ecclesiastical though the boundaries were not identical.

The Service Register of the Church begins with Mr. Shelton’s Institution by the Bishop of Ely at 3 p.m. on Saturday, 8th November, 1913. The Clergy in the Deanery attending included then, a Rector of Hulcote and a Rector of Pottesgrove. The Reverend G. H. Watson remained as Curate.

Marginal notes in the Register are few, but they show the concerns of the time. June 12th, 1914 – Intercession for the Welsh Church, and then August 11th – Intercession; August 13th – Intercession. On August 16th – a collection for the Prince of Wales National Relief Fund. The word “Intercession” occurs in the margin six times more, but then after the middle of September not again. At the beginning of 1915 a “Day of Humble Prayer Relative to the War” is recorded. There is no further reflection of the war until October 31st, 1915: “There was no Evensong this day owing to the new Lighting Order, and the inability of the Churchwardens to get windows darkened.”

The Service Register and the Vestry Minutes fail strangely to indicate passing events.

The Feast of Saint Michael occurred on a Sunday in 1918. There was a Celebration of Holy Communion at 7 a.m. with 21 communicants, and 49 communicants at 8 a.m., a special Preacher at Matins and Evensong, and a Collection of £7 7s. 5d. to be divided between the Clergy Orphan School and Bedford Hospital – but apparently no-one noticed that Saint Michael’s Church was now half way to its Centenary.

Again, on November 10th, 1918 – a Sunday – there was a Celebration of Holy Communion at 8 a.m. with 24 communicants, Matins at 11 a.m., Evensong at 6 p.m. and the collection of £2 15s. 11d. for Sunday Schools. The next entry is the regular weekly Communion on November 14th at 8 a.m. with 6 communicants. Nothing is recorded for November 11th or the day following.

On a Sunday following, Bishop Hodges preached at Matins, but then Bishop Hodges lived in the Parish, and he liked to preach at Matins. He wrote down his text in the Register – “Psalm 94.”

Psalm 94 opens: “O Lord God, to whom vengeance belongeth . . .”

At the end of our first 50 years it was little realised how the world had changed, and how the Church too was changed.

Interlude We find it hard to realise the extent to which we are living history. Returning for the last time to the old Minute Book of the Annual Vestry Meeting, we look at the lists of names of those present each year.

In the earlier accounts we find a distinction between “Esqre.” and “Mr.” that disappears in the early Eighties; but more interesting is the entirely male presence of the earlier meetings. Annually, for 34 years, there is no female name among those present, and the break does not come until 1902, when there are 25 present, including the Churchwarden’s wife and 2 Spinster Ladies. Next year, the Churchwarden’s wife alone ventured to be present, but in 1904 the same three ladies are present. In 1907, the Churchwarden’s wife is the only lady there.

The good lady would possibly have expressed abhorrence at the mention of the Suffragettes, but in her own way she was blazing a trail. In 1910 she was there by herself, the only lady. In 1912, no ladies were present, but that in itself may have brought forth expressions of surprise, for now their presence was an accepted fact.

We close the book, however, with the last meeting of 1921, and still there is no record of any lady addressing any remark at any meeting; and that – to us at least – may cause some surprise.

THE TWENTIES It was decided to furnish a Memorial Chapel – now generally called the Lady Chapel – in memory of those who died in the war. A later generation may not have much admired the furnishings, but the important fact was that there was now a small chapel for weekday Services where worshippers could feel a greater sense of “togetherness.”

The work of such men as William Temple and Dick Sheppard in the “Life and Liberty Movement” was to give to the Church at last a measure of self-government; but the setting up of Parochial Church Councils was not universally welcomed. In this Parish, the Vicar, one of the first members remembered, “hated us all” and thought “it an iniquitous thing to have”; but the law now demanded the setting up of P.C.C.s.

Accordingly, a first meeting was held on April 21st, 1920, at which “the only business was to elect the Vice-Chairman and Secretary.” There was a second meeting four days later to “co-opt a member.” The Council, thus being formed and its Office-bearers chosen, it never met again that year.

In the following years matters of finance made meetings necessary, and they were eventually held about once a quarter. The objects of particular financial concern are an indication of events. A Vicarage Fund was needed, as the Duke was handing over his control. Certain out-buildings were pulled down, and a space was reserved for a Church Hall.

The Assistant Curate Fund came into being, as after a gap of six years the Reverend C. H. Gilson came to Woburn Sands as Deacon in 1927. He was set visiting from 2.30 until 5 p.m. every day except Saturday. As there was little to do in the evenings the Curate used to play bowls with the men or go to see various invalids.

With the Vicar’s knowledge and consent, he started to say Matins and Evensong daily in Church. The Vicar (Mr. Gilson recalls) always used to wear stoles for all the Services – never a scarf, though Vestments were not used.

The provision of his stipend of £225 had to be met. The Vicar was “not so vigorous as he had been,” but in 1929 there was to leave the last Assistant Curate of Woburn Sands.

Mr. Pettit, who had been Churchwarden for a time, is remembered as rather autocratic, and as riding down on his horse from his home at Croylands. In 1928 he had the Ellen Pettit Memorial Hall built next to the Vicarage in memory of his wife. This meant that the Sunday School could discontinue the use of the Council School. But it also meant a new financial concern, including the immediate purchase of 180 new chairs at 4/- or 5/- each.

In a 1921 magazine which has somehow survived, we read: “a discussion . .. evoked the fact that, there are some who do not like the girls being introduced to the choir stalls. We were under the impression that these were days when women . . .” Change was to be seen at all points, except on the front cover of the Magazine, where the same block of the Church interior was in use from 1894 to 1946.

Interlude The endless heated discussions over the years about the Quota that the Parish is called to pay to the Diocese can only be seen with a smile, if we are to regain a sense of proportion; for central organisation always tends to create a “we” and a “they” locked in a struggle that only laughter can break.

The first mention of the Quota is in May 1921, when it was fixed for the Parish at £112 – “the general opinion was that the amount will be unobtainable.” And general opinion was quite right, for the amount that was obtained was £34, and this became the new assessment.

In a letter from the Bishop, circulated in the Diocese, he asked for £100,000. This was in 1925. By 1927, the Bishop had come to the conclusion that the sum to ask from the Diocese was £25,000.

In 1927, “having managed to meet the £34 per annum” the new assessment was again fixed at £112, and “that amount was absolutely out of the question.”

The quota was now fixed at £45.

At the last meeting of the P.C.C. in 1928, the Minute Book reports: ” Mr. Gilson, the Secretary for the quota, in spite of his utmost endeavours had been unable to raise more than £41 6s. 0d. There was, therefore, a deficit of £3 14s. 0d. and, in view of the promise of its representatives, the Vicar thought. . .”

But perhaps we have had enough of Diocesan Quotas, so let the Vicar keep his thoughts to himself, whilst the 1967 P.C.C. member notes the present figure of £316.

THE THIRTIES

In the Twenties there is a sense of change and adaptation, which seems lacking in the thirties. Mr. Shelton had entered upon his seventies. S. Michael’s Church was being served faithfully with a fine continuity of service. One of the Churchwardens had held office since 1921, and his father was at the first Vestry Meeting of 1868. The Organist, Harry Seabrook, had held the post since 1893. All three were to continue well into the Forties.

Some changes did take place – the installation of electric light into the Church in 1930, the building of a kitchen to the Memorial Hall, the addition of the Chancel Screen in 1936. Then the Organ needed attention. The Church clock needed attention. The District Visitors were to arrange a house to house collection; and always each year there was a general meeting to arrange the Summer Fete.

Otherwise, in the mounting stress of the Thirties, life at S. Michael’s went on the same. Take a Sunday at random – the second Sunday in September, and look at the Register for each year from 1930 to 1939. The Services are: 8 a.m., Holy Communion; 11 a.m., Matins and 6 p.m., Evensong; with an occasional Children’s Service at 3 p.m. The number of Communicants on this Sunday over the years are: 20, 38, 23, 31, 35, 31, 24, 29, 27, 30. On the last of these, there appears nothing special in the Register, no call to “Intercession,” but once again Britain is at war.

Interlude John Shelton writes in the Parish Magazine of September 1939:

“It seems almost as though a great shadow may be upon our Nation and Empire as we keep this our Patronal Festival – even the shadow of war. Let us still hope and pray that our beautiful world has not run so wild and mad, through the folly of a few rash men, who seem to seek nothing beyond their own way of folly, with all the suffering and agony which it cannot fail to bring to millions of the sons of Peace throughout the world. As I write today, none of us can tell what awful and momentous issues hang in the balance of the next few days. Do not let us lose heart! Let us still be men of Prayer, believing in the invincible Presence and Power of God, Whom we will trust and not fear, ” though the earth be moved: and though the hills be carried away into the midst of the sea.”

THE FORTIES

The years of the war were not easy, though the taking over of the Memorial Hall by the military relieved one major financial problem, but only one – £18 was accepted in 1945 as the Parish target for the Diocesan Quota.

Six fire buckets and an outside ladder were ordered for the Church to meet the fire emergencies of war. Evensong in the winter was moved to the afternoon. The Vicar had to have a car to take him up to Church, and was much helped by the Clergy in the district. He finally laid down his reins of office in 1946 at the age of 86.

Perhaps the last picture of Mr. Shelton, who served Saint Michael’s Church so long, can be of the small frail figure entering the Church for a Special Service on VE Day, when the war with Germany was ended, and of his happiness to find it “packed to its utmost capacity, and the heartiness of the whole Service testifying to its reality.”

There followed a long interregnum from early March to late October 1946, when the Reverend Frederick Bowler came from a Chaplaincy in the Forces to be Vicar of Woburn Sands.

His drive and enthusiasm was what was needed. He organised a Communicants’ Guild in three Wards, for different ages, so that there was a place for everyone. He organised regular social events, so that “the Memorial Hall is a hive of activity on most nights of the week.” He began a new magazine for the Parish – “Forward,” which was a well-produced publication at 6d., but could never pay its way and was discontinued when he left. The heating arrangements of the Church were renewed, and a group of the Congregation who called themselves the “Fireflies ” put on events to raise money for it.

He restarted the daily Services in Church, including a daily Celebration of the Holy Communion at 8 a.m., but perhaps he, and others too, would see as his most important work the starting of a Sung Eucharist each Sunday at 9.15 a.m. This was begun on Easter Day 1947, and at the same time the other Services continued as before: 8 a.m. Holy Communion, 11 a.m. Matins and 6 p.m. Evensong.

Frederick Bowler was long aware of a call to serve the Church overseas, and accordingly he left in December 1950 to take up work in Borneo.

Interlude At this point the writer is aware that he is about to come upon the scene. He wishes he could slip in from the wings as part of the chorus, but he knows that he cannot altogether avoid the limelight, and therefore the criticism of his performance. Yet he has been so much with the events and records of the past that he forgets himself in seeing himself as part of the Continuous story of the Church.

There is still one-sixth of that story to tell.

He is aware of the impossibility of choosing one or two trees to illustrate a whole wood, for this he must do. He is equally aware of the inadequacy of what he has written, of the great names that he has omitted. It is impossible to begin to tell them, and names have only been mentioned to illustrate the story.

At the moment, two little pictures are in the writer’s mind, which are within his experience, and yet belong so much to something that is sadly gone – something of the past. First, it is Sunday Evening and the Evening Service has just begun, but coming up the centre aisle, always a little late, is the small, almost shrivelled, figure of Mary Mowbray, making her way to the front seat under the pulpit. She puts down her candle lantern, which has lit her up the steep jitty from Hardwick House. Her sister Edith looks up from a few rows behind. Mary, in a fashion of the past, which a man dare not begin to describe, with a weight of rings on her fingers, looks about her, her lined and pointed features giving her a sharp look, as though her whole face, and not just her lips, was saying : “There! I have arrived!” This parish has known its “characters.” Alas that they are gone.

The second picture belongs not to Sunday Evening, but to Saturday Morning – pocket money day. The children clutching their pennies have gone up to Mrs. Richardson’s little Sweetie Shop on the corner of Woburn Road and Church Road. The shutters are down and removed. The shop is opened.

Inside – from the bell on the door to the low ceiling with its hanging oil lamps, from the rows of jars of sweets to the tins of toffees and the boxes of bars of chocolate – this is all that a Sweetie Shop should be.

Mrs. Richardson has time for each child, because she knows that they have important decisions to make. She has no need to guide them, for they know their way to the section where all the halfpenny purchases can be surveyed and considered.

We leave the children spending their Saturday pennies, and we move away from our memories, because it is not only the shutters that have gone up for good. The wooden counters of the shop are bare and empty. Something more than a little village shop has closed. Alas! That this too has gone.

THE FIFTIES The Institution of the Reverend Michael Meakin took place on 8th of March, 1951. On coming he had been as impressed by the architecture of the Church, as he had been depressed by the drab and faded furnishings. The shortages caused by war were beginning to disappear, and as a first step the redecoration of the Lady Chapel was begun. The Screen was a matt green. The Tester and Altar furnishings were dull red. The walls were covered with dirty stencilled hessian of greenish-blue. The ceiling was blue. It was a depressing hindrance to worship. Blue and ivory were the colours chosen, and a wonderful transformation was made at no great cost.

Gradually, other parts of the Church were given cleanliness and colour. New Altar furnishings were made. Old hangings were removed. New Vestments were bought. Additions such as the fine Portuguese Cardinal’s Chair were made. Steadily and slowly, Vicar and Congregation together worked to make the Church a more beautiful place of worship.

Fetes and Sales were a great success in the late Forties and early Fifties. Many shortages meant that there was a ready market for almost anything, but gradually plenty was coming back into the shops, and it was becoming less easy to raise money in this way.

Slowly, a principle was becoming accepted – that all money needed by the Church should be raised by direct giving. The twice giving of a Sale of Work and the raising of money by Jumble Sales showed an improper valuation of the Church. The P.C.C. had since it began, been concerned with little else than money. All this was bad for the Church. When Fetes and Sales were abolished as means of money raising, we needed about £200 to balance our budget; and so we had a special appeal which we called the Double Century. This served its purpose for some years, but eventually, with the Promise Sundays of November giving opportunity for each member to make an annual promise of their share of the prepared budget for the coming year, parish finance was put on a sound footing. The P.C.C. could give time to other matters. The Summer Event in the Vicarage Garden could be a wholly social occasion; and our annual expenses were adequately met each year.

The Sunday Services continued as in the past, at 8 a.m., 9.15 a.m., 11 a.m. and 6 p.m. Christmas 1952 saw the first Midnight Mass. Occasional Communion Services were held in the Memorial Hall for those who could not climb the hill to Church.

The tremendous burst of activity of Mr. Bowler’s time seemed to have spent itself. Some notable social occasions took place, but they were becoming less frequent. Youth Clubs in the Hall flourished and died and started again. The Mothers’ Union met, but seemed not to grow. The Sunday School had two notable Festivals in the Summer, but a change seemed to be coming. Children were no longer being “sent,” and some, particularly the older, stopped coming.

The Fifties saw many changes, of which we could never be really aware at the time. It was part Post-war reaction, part the coming of Television, part the affluent age with its motor cars for almost all – social habits were changing. Church going was no longer the respectable thing to do. The Vicar of a Parish was no longer accepted for what he was. In the Fifties these changes were puzzling and sometimes painful, but they were purging and purifying – for those who remained.

There is too ample material for a history of this period. After a brief participation in the Fleete Chronicle, in January 1953, a new Parish Magazine was started. It was less ambitious, duplicated with a printed cover, selling at 3d. – “The Signpost.” Fourteen years later it continues, and the price, with other prices soaring, has only risen to 4d.

Turning over the pages of the bound volumes, the eye is caught by headings – Michaelmas Goose, the Saturday Market, Coronation T.V. in Memorial Hall, combined Hungarian Relief, the 1956 Pageant of History, Archery, C.E.M.S., and so on and so on. Some little reminder of the many activities of a decade.

Interlude On Tuesday, 3rd September, 1963, the Vicar of Woburn Sands is with a group of other Clergy at a Sung Eucharist in Toddington Parish Church. They are members of a Priests’ Fellowship which meets monthly.

The Church is beautiful. The Service is full of dignity in worship; but the Vicar’s heart is heavy. He can remember the agony of that morning – his ministry at Woburn Sands seems dead and fruitless, and his own spiritual life completely barren. God seems very very far away.

After the Service, they go to the Church Hall – a converted cinema – for an hour’s Greek New Testament, followed by a picnic lunch. After lunch the host, John Gravelle, is supposed to give a paper on some subject or other, but he excuses himself, and asks if he may instead play a tape recording of a certain American Priest, Dennis Bennett. The recording is not too clear, and the hall echoes a little; but the present writer catches part of what is said and his interest is held. Dennis Bennett speaks of a real experience of the power of the Holy Spirit, as in New Testament times, of the neglect by Christians today of the gifts of the Spirit. “We are not using the weapons.” He talks of “speaking with tongues.”

Returning from that meeting, the Vicar is driven to his Bible, and studying all references to the Spirit. It was the beginning of a personal experience that has been enriching in a manner unbelievably wonderful. Faith becomes of the heart as well as the head, and yet it somehow is not emotional. Space does not allow him to tell of all his own particular pilgrimage.

He gets a copy of the recording, and invites little groups of parishioners to the Vicarage to hear it. Most of them are not impressed – yet.

He calls a meeting in the hall and gets John Gravelle and Eric Houfe to address it on the experience in their lives of the Holy Spirit. At the end he invites those who are interested to go further to tell him, “not now, but tomorrow or some time later.”

Perhaps 60 came to the meetings in the Vicarage. Perhaps 30 came to the meeting in the hall. Two speak to him about it later – but they are the two Churchwardens, and they speak for their wives too, so that with the Vicar and his wife, that makes six. They start to meet regularly in a private house – to share their experiences, to help each other in their difficulties, to pray and praise together – to become conscious of the warmth of fellowship that is meant by being the Church.

Very slowly that little group has grown and split into two and been strengthened. We make our mistakes. At times we talk too much. We live and learn. Yet we all know that we have something that we had not before. God’s Spirit is indeed working within us. This we know.

THE SIXTIES

At the time the events of the Fifties were confusing and sometimes seemed wholly retrograde; but now it is possible to see them in a clearer perspective. In the same way, our assessment of the Sixties may appear later to be wrong, and insignificant details may prove themselves to be the most significant.

Change in the Church at large is reflected in the local Church. Ecumenical contacts increased. The Methodists and Anglicans combined to keep Christian Aid Week, and soon a sum of over £100 was sent annually from the village. Joint Services and a joint Garden Party were arranged. Soon the Roman Catholics joined them. A combined Service in the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity was held. Combined social action in “United Christian Service” was organised.

The Vicar of Woburn Sands, like Mr. Mosse before him, became Rural Dean. Perhaps the most notable event of his seven years from 1960 to 1967 was the start of the Annual Deanery Evensong on a Sunday, held first at Eversholt in 1960. Fleete Chronicle came to an end and was replaced by a Deanery Newsletter, which was in pattern like the Signpost, and produced at Woburn Sands.

Each year brought its change. Bowling eggs on Easter Day was first started in 1954, but in the Sixties had to be discontinued because of the vast increase of traffic down Church Road hill. A monthly Family Service at 3 p.m. on Sunday flourished for a time. But a major change was made in the moving of the Sunday School to 11.30 on Sunday morning, which brought many more children to attend a Service or part of a Service in Church, and the Sunday School built up again steadily from the time of the change.

Two things belong particularly to the Sixties. The first is the start of the House Meetings. By the middle of the decade there were three House Meetings a month – two were general meetings and one a House Communion. The reality of the fellowship at these meetings has had its influence gradually upon the whole congregation. There is an ease and a spirit of welcome to all at these meetings that saves from any danger of “exclusive sets.” It is the desire of all who experience the fellowship at them, that others will start in the Parish, none over about ten members that the close friendliness be not lost,

Secondly, liturgical change is in the air in the Sixties. S. Michael’s is a Congregation willing to make changes if they are wise and good. One experiment started was on the occasional fifth Sunday of the month, when all three Sunday Services and Sunday School were united in one Service – a Parish Communion at 10 a.m., with particular thought for the children, that the worship might be both happy and meaningful for them.

What was to be done to mark the Centenary? The blank brick wall of the Chancel had stood for 77 years, making the Church unfinished. In 1966, at a cost of about £3,000 the outside brick wall was faced with stone, and two windows were placed in the wall to let in light to the Chancel and Sanctuary. It transformed the Church, for what should be most conspicuous, namely the Altar, had always stood in the darkest corner. Carpeting of the aisles with a rich red carpet at the same time worked a transformation in the Nave.

There was still much to do and much to prepare, but S. Michael’s Church stood a little more ready to celebrate its Centenary on Sunday, 22nd September, 1968. All praise be to God.

An Unfinished Sermon for the Centenary

I remember calling on an old man on the day that he reached his centenary. According to custom he had received a telegram from the Queen. The daily paper had arrived at the same time. When pressed by those round him to open his telegram, he put it off, for he was busy as usual with the paper studying the prices on the Stock Exchange.

We on this Centenary will not be over-busy with the facts of the Church’s building and history, to forget that our chief occupation must be our communication with the All-Highest.

We are met here, first and foremost, to praise God. It is with thankful hearts that we assemble, for God has indeed been gracious to each in our turn who have received blessing and strength in this place.

This is no undervaluing the history of the hundred years from 1868 to 1968. Indeed, I believe that we shall each read the passing events of those years with a deepening sense of the working out of God’s purpose. There have been mistakes. There have been follies. The sin of man is there, and yet the words of God shine through, even though the writing is in man’s hand.

Having lived with the events of the past of this Church for some time, and having been able to record just a few of the events of that story, I find in each decade a different “feel.” This, inevitably, leads on to the question – what will the “Seventies” bring forth?

God is at work. God is working out His purpose. We do not suggest that the working of God is to be found in our Church alone. He is at work everywhere where men seek to work together with Him. He is at work here.

I see in the Seventies perhaps the time of the greatest movement of God among us. We have been painfully purged of our false preconceptions and our proud presumptions. We acknowledge our Heavenly Father as supreme. We know His Son as Saviour. We know the Holy Spirit as power in our midst. We see in the Being of God the perfect pattern of unity and peace. We have a true sense of our own weakness and dependence.

Now God can act. Now God will act. Prayerfully, expectantly and hopefully we must stand ready and waiting, that God may act through us. We must meet together and wait upon God, that the voice of prophecy be heard amongst us, and be approved by the Church. We must be as disciplined and prepared as any army in the field, for the old Enemy is the most formidable foe; but our Captain is One Who has already won the battle.

This Centenary is a time for the briefest of looking back. It is then, a time of looking forward. We may at times appear to be a pretty wretched sort of army, but that is to look at us and not at the weapons put in our hands by God. The future contains our challenge and our hope. 1969 marks for us the beginning of ….

…and there the book ends! I am indebted to the Meakin family for their permission to republish this work.

Readers interested in a fuller history of St. Michael’s church are directed to Evelyn Wright’s book, “St. Michaels Woburn Sands, the Church, the Parish and the People” ISBN: 0952259303.

This was the sermon preached by Lord Bishop of Ely, Edward Harold Browne, at the consecration service at St Michaels in 1868:

THE WITNESS OF THE TRUTH.

Preached at the Consecration of Woburn Sands Church, September 22, 1868

St. John xviii. 37, 38.

‘Pilate saith unto him, Art thou a king then? Jesus answered, Thou sayest that I am a king. To this end was I born, and for this cause came I into the world, that I should bear witness unto the truth. Every one that is of the truth heareth my voice. Pilate saith unto him, What is truth?’

In every age and nation the judgment-hall is that which gathers round it all our associations of dignity and awe. In no age or nation has there ever been such a scene as this, nor ever shall be, till He who was then the culprit shall come again as the Judge.

I doubt if even the veriest unbeliever can read attentively the account given in the Four Evangelists, without sympathy with the Sufferer and respect for the calmness and serenity of His carriage in the face of certain death; death of so fearful a character, that the bravest would quail at the most distant thought of it. This composure of the accused contrasts with the eager malice of the priests, the excited fury of the mob, the terror of the disciples, but above all with the indecision of the judge. Armed with imperial power, a power which nothing earthly could withstand, Pilate, who had been the first that ever dared to bring the Roman envies into the sacred city, who had not shrunk from mingling the blood of his subjects with the blood of their sacrifices – the proud, imperious Roman procurator, hesitates, delays, temporises, argues, almost trembles, when he is called on to judge – to judge a Galilean Peasant, whose life would have been no more likely to be accounted of in Rome than the life of the wretched dogs which they annually tortured and crucified. Every utterance which comes from the judge is marked with hesitation. Every word which falls from the Prisoner is meek, calm, dignified, decided.

There can be little doubt but that Pilate, who now lived at Jerusalem, had heard somewhat of the reputation of Jesus; of His prophetic teaching; of His influence with the people; of His reputed miracles; probably of His entry into Jerusalem, hailed by the multitude as the Son of David, the expected restorer of the kingdom to Israel. Apparently all this had wrought on him a twofold influence. He naturally expected that Jesus might stir up the people to revolt, and so give trouble to his government; but he also felt some uncertainty whether there was not really a supernatural power, against which it would be dangerous for him to fight. His wife’s dream added to his own misgivings, and shook his resolution.

The words of my text follow immediately on a declaration by our blessed Lord concerning His kingdom. The Jews had delivered Him up to the governor, declaring that He was a malefactor and ought to die. Pilate probably but little cared for such general charges, nor for the religious questions which he knew to underlie them. But recurring to what he had heard of the claim asserted for Jesus to be the Messiah, the successor of King David, and which he thought most likely to be practical, he asks Him, ‘Art Thou the King of the Jews?’ The answer is firm, yet prudent. ‘My kingdom is not of this world. If My kingdom were of this world, then would My servants fight, that I should not be delivered unto the Jews; but now is My kingdom not from hence.’ There was no danger to the Roman empire from the kingdom of Jesus, because the one was an earthly, the other was a spiritual reign. The servants of Jesus were not men of war, and therefore they did not fight against the Jews, nor would they fight against the Romans; and yet they were servants, and their Master was a King. Pilate seems to have guessed this meaning, but yet he returns to his question, ‘ Art Thou a king then?’

And now let us mark what follows. Our Lord replies, ‘Thou sayest that I am a king,’ – a sentence which signifies, ‘Thou sayest that I am a king, and thy saying is true.’ Adjured in the judgment-hall to answer His judge, He shrunk not from declaring what alone would move the Roman jealousy and bring down the Roman judgment. And then He continues, ‘To this end was I born, and for this cause came I into the world, that I should bear witness to the truth.’ His acknowledgment that He was a king, when that acknowledgment was well nigh certain to crucify Him, was a witnessing to the truth, beyond any witness ever before uttered by lips of man. But what I would specially ask your attention to is this: Here, in the hour of greatest peril; here, in the agony of deepest conflict; here, in the struggle of death – of death to the Saviour, but of life to them that should be saved; the Royal Priest, the priestly office, about to offer up the eternal sacrifice, and soon to take unto Him the kingdom which shall have no end, yet declares before the world and the world’s representative, that the great end of His incarnation into the world was, that He should bear witness unto the truth.

We might have thought that He would say, I was born that I might die as a sacrifice and so save the world. We might have thought that He would say, I was born and was made Man, that I might reign over God’s kingdom, and might raise those who would follow Me to reign in that kingdom with Me. But what He does say really is, ‘I was born that I might speak the truth.’

I do not think I need delay to show that there is no inconsistency in this with other sayings or other teachings of Christ. What, surely, we cannot doubt is this, that by thus and then declaring that the very purpose of His mission from heaven was truth, the proclaiming truth and testifying to truth, our Lord lays an emphasis on truth, and on the importance and necessity of truth, which could not be equalled, if it were blazoned with the trumpet tongues of men and angels from pole to pole and from sphere to sphere.

But, if the time at which our Lord uttered these words gave them a significance which cannot possibly be exceeded, there was never a time in which they were more needed, and the lesson to be drawn from them was more pregnant, than this present time in which we have to live. We have been used to hear it called an age of light; but we may still more truly call it an age of doubt. Light we have indeed, light from heaven, – but we have cross lights, and counter lights, and false lights, and lights of every colour and every shade, till their flashings and glimmerings daze rather than guide us, and the meeting waves seem often to produce not light but darkness visible.

I am not making an accusation, but stating a fact. The light of earthly knowledge has sprung up amongst us almost against our will. At all events, we have been as powerless to shut out its rays, as we should be to stop the flood tide of the ocean. Half a century has brought us news from stars above, from rocks and subterraneous forests beneath, from distant shores, from buried cities, from languages lost to the world for almost untold centuries. New knowledge has brought new problems, and hard problems need hard heads to solve and disentangle them. Political changes conspire with scientific discoveries to change the thoughts of men. And, judging from all human experience, we have but little cause for wonder, that ancient, uninquiring faith has too often been shaken or overthrown, when even some of its assailants have been those enlisted and sworn to maintain and to defend it.

There is another thing not quite so excusable, which must not pass out of sight. The age is an age of unexampled wealth, unknown luxury, restless speculation, rapid and often reckless expenditure; in short, of the highest material prosperity, and so of the most deep-seated worldliness.

One thing more I must add. There is, God be praised! still, and even increasingly, much religious zeal and self-devotion – but, with all, the aspect which religion presents to the half-heedless world is in an aspect of disunion and almost of discord. I gladly acknowledge that in every one of the great schools of thought within the Church there is much earnest, active piety, that in those, who are without the Church of this land, whether they be of the communion of a great foreign Church, or one of the many varying sects around us, there is also much of self-devotion and godliness. Yet to the world, though all these several sections are really independent witnesses for God, it seems, at least, as if ‘ neither so does their witness agree together.’ And is not the result of all this – is it not almost inevitably the result – that the world is everywhere saying, and saying exactly in the same spirit, what Pilate said to Jesus, viz. ‘What is truth?’ Truth and error have alike been presented to it, and truths of different aspects and varying colours have been held up before its eyes, and one has been saying, ‘Truth is here;’ and another, -‘Truth is there.’ And the world is busy with its own thoughts. There is its merchandise and its politics, and its show of wealth, and on the reverse side its squalor of poverty, and with the one its self-indulgent sensuality, and with the other its struggle for very being; and it will not give time and trouble to search into and find out truth. And so it asks doubtingly, ‘What is truth?’ And, in despair of being satisfied, waits not for an answer.

This was just Pilate’s case, and it is just ours. In “the strange scene in that ancient judgment-hall, on the raised pavement of justice, which the Jews called Gabbatha, whilst in Christ we have, not only the embodiment, but the very Essence of Truth and Light, we see in Pilate the exact representative of prosperous worldliness. He was no worse than other men in like place. In the awful history of the Crucifixion, the character of Pilate comes out more favourably than priests or people, perhaps even than the Apostles themselves. But we see in him exactly the worldly ruler, the worldly statesman, the worldly idler and doubter. The Truth Itself stood before him in human form. The words dropping from those human lips rung in his ears. His conscience was stirred, his fears were roused, he was shaken in his judgment, and his resolution forsook him; but he was too truly the world’s child to throw his soul into the search for truth and to peril his prosperity for the attainment of truth; and he turned away with the scornful scepticism, ‘What is truth?’

You know what was the end. He believed, he proclaimed Jesus to be innocent; he had some misgivings even as to His descent from Heaven; but, for all that, he crucified Him. Is there anything to hinder a like consummation here and now? Christ is on His trial now before the tribunal of the world. Clothed in imperial purple, the world is sitting in the judgment seat on the raised pavement of its paraded impartiality, and Christ, in His word, His Church, His truth, is waiting the world’s verdict upon Him. It must inevitably be, if the world continues in its hourly increasing scepticism, that the world will reject its Saviour, though it will wash its hands, and proclaim itself innocent of the blood of this just Man. An age of doubt will give place to an age of unbelief; and the children of those who now only say, ‘What is truth?’ will deliver Jesus to be crucified, and His Church and His word to be cast out and trodden down.

My Christian brethren, the Church which is just built and in which we are met, is built to be one more prayers and its preaching, its Scriptures and its Sacraments, will all set forth Him evidently crucified amongst us. Will you hear the truth and receive the truth, that so the truth should make you free? Or will you turn away with Pilate, and wait no answer to the idle question, ‘What is truth?’

I know what the temptation is and thoroughly enter into it. It has been so with many of us, that in our infancy we learned of God, of an eternal judgment, of heaven and hell, of sin dragging us downward, and of the Saviour come from Heaven, that He might rescue us and raise us to that place whither He has gone up before; we were taught of God’s holy Word, of God’s blessed Spirit, of the Church of God on earth, and of the Church of God in Heaven: and we believed it all. But, with our opening reason or our advancing years, there came new teachers, or rather new unteachers. In books or in society, or in that most dissipating and disestablishing of all agents of this world the periodical and popular literature of the day, we had doubts suggested, and we listened to the doubts. All things of late seem to have become new; and our own old-world faith, and our old hopes and fears, were they but the prejudices and the dreams of childhood – the world’s childhood and our own? And is there nothing true, or at least nothing certain, but the world and the world’s creed, and the world’s honours, pleasures, or miseries? And I know, brethren, that in the present conflict of opinions, and with the specious arguments of unfaithful teachers, it is very natural for the occupied or the ignorant, for one who has not time or learning that should probe all questions, to turn away from every such question, busied in present labour, in present study or in present idleness, perhaps in present sin, and to let the future – the eternal future – take thought for itself.

But, O my brethren, for your own sakes, for your country and your children’s sake, I pray you not thus to yield to doubt and indifference and indolence. At all times doubt is easy, and faith is hard. And it was never more so than now. But if there be any, even the barest possibility, that the faith of Christ is the truth from Heaven, then doubt is infinitely dangerous to ourselves and to all with whom we have to do. It is dangerous to ourselves, for it is a growing infirmity. Like other weaknesses, it palsies more and more the heart that yields to it. And, like panic terrors in the day of battle, it infects our neighbours and comrades, spreading all around us its enfeebling influence.

You may not be able to solve every difficulty. You may not see clearly how science, as at present deciphered, fits into Scripture, as at present interpreted. You may not be able to settle all differences between conflicting sects and contending interpreters. But I am quite certain that you cannot remain in a more perilous attitude, than in thus burying your head in this world’s business, hiding your eyes from danger, and so hoping to be safe. Even a manly unbelief is more hopeful than such cowardly scepticism. And, moreover, I am sure of this – would that I could communicate my assurance to every one of you – that the earnest, faithful, humble seeker after heavenly light shall not be left in the darkness of doubt. Heaven cannot be won by sitting still: but the violent take it by storm. It requires, indeed, active seeking, honest seeking, and humble seeking; but then it will be found. There is a promise from Him, who before Pontius Pilate witnessed to the truth, and that promise is this: ‘ If any man is willing to do His will, he shall know of the doctrine.’ If the heart, the will, be in the right place and in the right course, a light from Heaven shall rise up upon it, and shall lead it home. The promise does not stand alone; it is repeated in various forms in the Old Testament, and in every portion of the New.

And remember what it was that Jesus Christ so earnestly witnessed with His dying words in His most pressing danger. His witness was, not only to the truth, but to the deep value, the worth and need of truth. He came into the world – God was made man – that He might bear witness unto the truth. And then he added, ‘Every one that is of the truth heareth My voice.’

These are very serious thoughts for us. The world’s teachers are fond of telling us that the end of Christ’s religion is to elevate our morality, and that we need aim only at this, letting divines fight about the rest. But Christ ever tells us that the end of His teaching is Truth. He is Himself the Truth. Truth, if embraced, shall make us free, free, i.e. from the power of sin, the slavery of death. The knowledge of God and of Christ, whom He hath sent, this is eternal life. These are Christ’s own sayings, and they are the very opposite of the world’s. The world, on religious questions, always asks, ‘What is Truth?’ Christ, in the same question, always says, ‘I am Truth.’

Let us choose which we will say. The one may possibly crucify us in this world, as it crucified our Lord; but we had better die with Him here, that we may reign with Him hereafter, than choose the world’s alternative; ask ‘What is Truth?’ not trouble ourselves to get an answer; then, though reluctantly, take our stand with the enemies of all Truth, wash our hands in self-asserted innocence, and at last crucify Christ.

Indecision is the ruin of more than half the world. Want of earnest seeking, want of decided action, let slip our best hours and our brightest opportunities. We grow less and less able to think for ourselves; and at last are inevitably carried on by the crowd, a crowd such as that which from its utter heedlessness, rather than from conviction or malignity, forced Pilate to give sentence against the Saviour.

Let us resolve, brethren, that it shall not be so with us – rather resolve to find out truth, to hold fast truth, and to hold up truth. It is worth every struggle, and it will repay every pain. And when once again the Son of God shall appear in the judgment-hall – whilst the fearful, the unbelieving, and everyone that loveth and maketh a lie shall be on the left hand; those who have lived in the Truth, and loved the Truth, and walked by the light of the Truth, shall reign with Him for ever in truth and light and love undimmed and unchanged for ever.

Page last updated Dec. 2018.