The 1908 Eastwoods Brickworks Accident

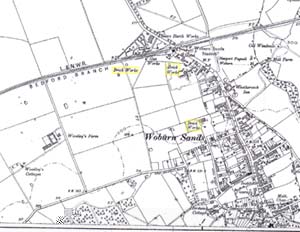

On the morning of Saturday, October 24th, 1908, Charles David Griffin, a young labourer of Weathercock Lane, was helping to remove the hot ballast earth that was heaped over one of the brick kilns at Eastwood’s Brickworks, by the station in Woburn Sands. The earth was piled up on top of the kiln to insulate it whilst firing the bricks. It needed to be removed so that the kiln could be repaired.

Charles was born in 1880 to David and Annie, who had married in Woburn Sands in 1878. David was an agricultural labourer and Annie a hat sewer. He was the second of five children, and was living in Aspley Hill at the time of the 1891 Census.

The best report of what happened that morning comes from the Leighton Buzzard Observer, 27th October:

“Woburn Sands. Terrible Accident. Kiln Roof Gives Way. Young Man Partly Buried in Hot Ballast. Heroic Conduct of a Fellow Workman.

The Woburn Sands brickworks were on Saturday morning the scene of a terrible accident, in which a young man named Charles Griffin met with injuries of a shocking character.

On the previous day, one of the large brick-burning kilns had been emptied of its finished contents, and as the management had decided to repair the domed roof, it was necessary to clear from the top a large quantity of what is known in the trade as ballast, being brick earth placed on the top for the purpose of keeping the heat in the kiln. During the process of burning this ballast gets red hot, and retains its heat for a long time; consequently on Saturday it was intensely hot. The unfortunate young man, Griffin, who is about twenty-six years of age, was engaged with five others in removing the ballast, when the part of the roof on which he was standing gave way, and he was precipitated into the empty kiln, with the hot ballast falling round him.

Fortunately he fell on his feet, but such a huge quantity of stuff fell with him, that he was imprisoned up to his waist and held as in a vice. What his sufferings were it is impossible to imagine, but those who were near say his cries for help were heartrending in their agony. Word soon went round the yard that a terrible accident had happened, and scores rushed to the spot anxious to help in the work of rescue. This was rendered extremely difficult owing to the heat, with the fact that there was only an aperture large enough to admit one at a time, while the air was so impregnated with dust that very little could be seen.

A young man named George Smith went down and dug away from the imprisoned man the calcined earth. When it had been got away, the victim was removed from his terrible position with as much care as the circumstances would permit, and driven in a cab to Dr. Brander’s surgery, where he was speedily attended to. The Doctor’s examination revealed terrible injuries.

Practically the whole of the skin was burnt from both legs up to the waist, while the skin of the arms was also burnt away. The body was uninjured, but two nasty cuts were received on the head from falling bricks. As soon as possible the unfortunate young man was removed to the hospital at Woburn, where further attention was given him. During the whole of this terrible experience, he remained conscious, and bore the excruciating agony with great fortitude. The report received from the hospital on Sunday was to the effect that he was going on as well as circumstances would permit, although, of course, it was too early to say what hopes there were of ultimate recovery.

The action of the young man Smith in rescuing the imprisoned sufferer is beyond all praise. He cheerfully faced what was an exceedingly dangerous task, and it is to be hoped his heroic conduct will be suitably recognised. To be underneath a roof which had been proved unsafe, with some tons of red hot earth on top which at any moment might come crashing down on him, was calculated to test to the utmost his pluck.

Griffin had not long been working in the yard having been out of a situation for a long time previously. It was a mercy the whole of the roof did not give way, as, if the six who were working on top had been precipitated into the kiln, the consequences would have been fearful. It was rumoured that the roof gave way owing to the violent oscillations set up by a passing train, the line being quite near.

[By Telegraph]. (From the Woburn Hospital). Patient going on so far satisfactorily.”

———————————–

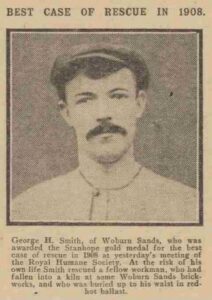

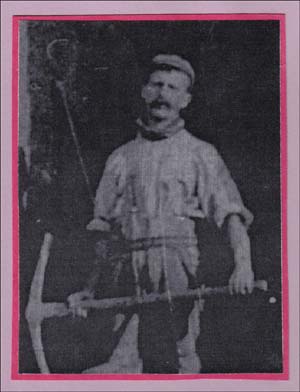

George Henry Smith had been born in 1886, in Farcet, just south of Peterborough, to William and Whybree Smith. (Research on a “George Smith” would be particularly difficult without his mother having had such a unique name!) By 1901, his family had moved to Woburn Sands, and were living at The Leys Farm, where his father was the farm foreman. George was their oldest surviving son, and had already started work as a brickyard labourer by the age of 15. The next week, the Leighton Buzzard Observer followed up with a photo of Smith, and another detailed report:

“The industrial history of our country would, if it was inquired into, reveal many acts of gallant heroism, in which men, and women too, have cheerfully risked life and limb to succour a comrade or a friend. Fortunately, not many of those who are entitled to hold a place in the roll of industrial heroes have been called upon to make the great sacrifice which they have so unselfishly offered, but whether or not they have paid forfeit for their bravery with their lives, they nevertheless deserve honour of all men and women. Surrounded by the glamour and excitement of war, nerveless men are been spurred to do deeds of daring which seem well-nigh incredible. But this incentive action is wanting in the case of those who, with intrepid daring, deliberately, and with full knowledge of the risk they run, offer their own lives in an effort to save others. Such are he industrial heroes of England.

Above we give a portrait of George Henry Smith, who, on Saturday week, performed a deed of heroism which compelled the admiration of all who were cognisant of the facts. As recorded in our last issue, Charles Griffin, an employee at the Woburn Sands Brick Works of Messrs. Eastwood and Co., Limited, was precipitated into the bottom of a kiln through the roof collapsing, and buried up to his waist in red hot ballast. Smith immediately went to the assistance of his workmate, making his way to him by means of the wicket, an opening through which the bricks are taken into, and removed from, the kiln.

The ordeal which the brave fellow went through can scarcely be imagined. But some idea may be had by realising a small chamber, perhaps eighteen feet by twenty feet, with a roof loaded with many tons of hot ballast, oscillating ominously, and threatening at any moment to precipitate its deadly load on the two young men beneath, one working feverishly to release his imprisoned friend, the other giving expression to heartrending cries as the hot earth seared his flesh. The rescuer’s task was much impeded by reason of the intense heat, the choking dust, and the poisonous gases which emanated from the chamber’s contents. When at last the work was completed, and Griffin was lifted out, followed by his rescuer, a sigh of intense relief went up from the hearts of those who had been silently watching the place where such a heroic struggle had been waged with death. From the time that Smith entered the kiln to the time the rescue was effected was about a quarter of an hour, but it took a long time for him to recover from the effects of his most trying experience.

George Smith, who celebrated his 23rd birthday on Thursday, was born at Farcet, near Peterborough, and has been engaged during the whole of his working life in the brick making industry, at present assisting his father, who is a brickburner. He is above medium height, somewhat sturdily built, and possessed of much muscular strength. Of a modest and retiring disposition, he seemed loath to discuss his brave deed when interviewed by our correspondent. When asked if he could describe his experiences while underneath the shaking roof, he replied that he had no time in which to think of anything but the task which he had set himself. He was prepared, however, to do the same again, should circumstances demand it.

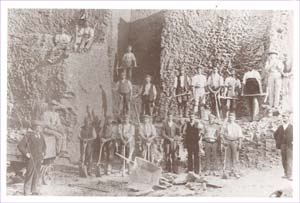

Mr. Mason, the works manager, described Smith’s conduct as heroic. The oscillation of the roof was so pronounced that he felt sure had a train passed by at the time the two were underneath, the whole of it must have collapsed. We are indebted to Mr. Mason for his courtesy in giving facilities for the taking of the photo, which shows the wicket of the kiln next to the one which collapsed.

We are glad to state the poor fellow Griffin was going on satisfactorily yesterday. If he recovers he will undoubtedly owe his life to his fellow worker.”

In the same edition, they also reported:

“A Deed of Heroism. On another page we give an account, accompanied by a portrait of the chief actor, of an exceedingly brave deed performed last Saturday week by a young man resident at Woburn Sands, named George Harry Smith. Deeds of heroism are by no means rare in the annals of industrialism, and whenever they occur they never fail, to arouse the admiration of all true men and women. Every man may be potentially a hero, but the opportunity is not given to every one to prove his ability to perform heroic deeds. It may be that many of the workmates of the poor fellow who was so terribly injured would have cheerfully faced death to release him from his agonising position, but the opportunity was not theirs, it was Smith’s, and right nobly did he avail himself of it. Let us not, therefore, be grudging in our appreciation of his conduct, giving honour where it is so richly deserved. With the object of making Smith a recognition in the form of some permanent memento of his bravery, we have been asked to open a fund, to which readers are invited to contribute. Contributions may be sent direct to the office of this paper, to Mr. A. G. Ellingham, Woburn Sands, or Mr. Mason, Manager of the Brickworks, Russell Street, Woburn Sands. They will be duly acknowledged in these columns. It is intended to form a small local committee to take charge of the arrangements, and to that end a public meeting will shortly be called, notice of which will be given in due course.”

Unfortunately, Griffin later died of his injuries. The Leighton Buzzard Observer, 10th November 1908:

“Woburn Sands. The Brick Kiln Fatality. Death of Griffin. Evidence at the Inquest. [by Telephone.]

The inquest on the body of Charles Griffin, who sustained injuries it the Brick Kilns, Woburn Sands, on October 24th, was held at the Weathercock Inn, by Mr. F. T. Tanqueray, Coroner, on Monday (yesterday) morning. Mr. Miller was elected Foreman of the jury. Mr. Leonard Ward, Inspector of Factories, from the Home Office, was among those present.

The jury viewed the body and afterwards went to the works and inspected the kilns. The first witness was Annie Griffin, mother of deceased, who said his age was twenty-eight. He was not insured, and was not a member of any club.

Alfred Mason, manager of Messrs. Eastwood and Co., Ltd’s., brick works, said that when he discovered the kiln was unsafe he gave instructions for the roof to be cleared and the middle wall to be supported with heavy timbers, also the chambers on either side of the one which gave way. There were four other men beside the deceased on the roof, who worked with pick and shovel, loading the ballast into the barrow which. Griffin wheeled. About 9.20 he was called up and found part of the arch at the front had collapsed and Griffin had gone down. He went up and saw George Smith inside uncovering Griffin’s legs. Griffin was ultimately got out and taken to Dr. Brander.

Mr. Mason, in reply to Mr. Ward, stated that direct instructions had not been given to have the whole of the roof shored up. He had a dry brick pillar put underneath the weak spot about a month before the accident happened. The kiln had been fired since, which would farther tend to weaken the roof. Witness could not say what was the average life of a chamber.

David Griffin, cousin of deceased, said he had charge of the gang who had been engaged to clear the ballast away. He deposed to receiving instructions from Mr. Mason, and he was told not to go on the end which was weak until made secure. About eight o’clock in the morning the bricklayer, Whitlock, came and said it was all right, and they could get on with the work. His opinion was that the roof of the chamber was totally unsafe, and that the work should not have started until made secure.

In reply to Mr. Ward, Griffin said Mr. Mason told him not to go on the weak spot, as it was dangerous. Soon after eight o’clock Whitlock, the bricklayer, came up and told him that it was safe, and they could get on with the work. William Whitlock, the bricklayer, was the next witness. He said he had examined the arch which gave way, and found one weak spot about four or five feet from the wicket. A brick pier had been put up to strengthen it. The arch had sunk in the shoulder. The same morning he was working under the arch to timber the wall up, and finished at 8.20. He gave instructions to the men on the top not to go on the weak spot. He did not tell them at any time that they might go on, neither did he hear Mr. Mason say that they were to wait for his (Whitlock’s) instructions. Mr. Mason had not given him any directions to see that the roof was safe. He told the men not to go on the weak places, but if they could not clear it any other way it was to be knocked in. David Griffin was the one he told not to go on. He did not tell Griffin it was safe. James Knight gave evidence. Walter Pointon and William Alfred Fisher who were working on top, next gave evidence. George Henry Smith, who rescued the deceased, also gave evidence. Dr. Brander gave evidence concerning the injuries to the deceased.

The Coroner summed up, and after some deliberation the jury returned a verdict of “Accidental Death,” and expressed the opinion that precautions ought to have been taken to shore the roof up before work commenced.

The Jury expressed admiration at Smith’s conduct in rescuing the deceased man.

Death of Griffin. The unfortunate young fellow Griffin, who was so terribly injured by the recent accident at Messrs. Eastwood’s brickworks, died in the Woburn Hospital on Friday morning. Needless to say, a large amount of sympathy has gone out to the deceased young man’s mother and sisters, while sympathy has also been expressed with Messrs. Eastwood, who are recognised as good employers.

The Smith Testimonial. A public meeting as held in The Woburn Sands Parish Room on Friday evening in connection with the G. H. Smith testimonial fund, the Rev. D. W. Henry in the chair. It was resolved that the fund remain open until Saturday, Nov. 21st, and the following were appointed a committee to administer it: The Rev. D. W. Henry (Chairman), Dr. Holmes (Treasurer), Messrs. Harrington, Hill, Ellingham, Boyes, and Garrod, with S. J. Southwood as Secretary.

The Woburn Sands Rescuer. First list of subscriptions to the George H. Smith testimonial fund:-

£.s.d. Name

1 0 0 Mrs. Dymond

1 0 6 Buzzard Observer

1 0 0 Miss Letchworth

0 2 6 Rev. D. W. Henry

0 2 6 S.J. Southwood

0 1 0 Mr. and Mrs. Ambrose

0 1 0 Mr. C. Dudley

0 1 0 Mr. A. E. Ellingham

0 1 0 Mr. B. Bathurst”

Griffin was buried in an unmarked grave at St Michael’s, Aspley Heath on November 10th, not far inside the gate, on the left. His funeral was reported on 17th November, again in the Leighton Buzzard Observer:

“Woburn Sands. Funeral of Charles Griffin. The mortal remains of poor Charlie Griffin, who lost his life as the result of the terrible injuries he received in the recent kiln accident, were laid to rest in the churchyard of St. Michael’s, Aspley Heath, on Tuesday afternoon last. Born in the village, he had grown to manhood, meriting the esteem of all classes, and because of that fact, and the tragic circumstances surrounding his death, a more than usually large concourse assembled at the graveside to pay one last tribute of respect to his memory. An only son, he was naturally thought much of by his mother, and as the funeral cortege left his late home, and wended its silent way to the Churchyard, her evident distress at the loss she had sustained strongly appealed to the sympathies of the onlookers. A large number of relatives followed the body, while his late fellow employees with Mr. Mason, the manager, joined in the procession in goodly numbers. The funeral service was conducted by the Vicar, the Rev. D. W. Henry, and the last rites at the graveside were of a very impressive character. Many beautiful floral tributes were sent, including an artificial wreath in glass case from the brickyard employees. The other wreaths, bearing suitable inscriptions, were from his mother, Mr. and Mrs. C. Barden (brother and sister), Mr. and Mrs. W. Brown (brother and sister), Mr. and Mrs. Green (brother and sister), Mrs, B. Linden and family, Mr. and Mrs. Giles, Mr. J. Wright, Mr. and Mrs. Mason, Misses M. and G. Griffin, Miss Swain, Mr. J. Bowler, Mr. and Mrs. Medcalf and family, Mr. and Mrs. Clare and family, Mr. and Mrs. Bodsworth and family, and several bunches of flowers from other friends. The funeral arrangements were satisfactorily carried out by Mr. J. Pikesley.”

Yet the local collection of money for Smith was not the only recognition he received. The Royal Humane Society honoured him with the silver medal for saving life. One recipient of this medal was chosen each year to also receive the gold medal of the Society, known as “The Stanhope Medal”. On February 27th, 1909, Smith went to Marlborough House to be presented to The Prince Of Wales, president of the Royal Humane Society. Admiral Sir George Digby Morent (deputy chairman of the RHS) described how there had been five silver medals awarded for 1908, but the committee had unanimously decided that the Stanhope Medal for 1908 should go to Smith.

This Gold Medal was accompanied by a £5 gift. The Prince of Wales told Smith he was “exceedingly pleased to meet such a brave man, and hoped he would live long to wear his medals and feel proud of an act of bravery which was of no ordinary character.” Sir William Bull M.P. thanked the Prince on behalf of the Society.

This was not the end of the recognition of Smith’s act of bravery. On 22nd July, 1909, Smith went to Buckingham Palace to be awarded ‘The Albert Medal’ 2nd Class, by King Edward VII. This is a bronze medal with crimson enameling, and is one of the top civilian awards for gallantry in saving, or attempting to save, life this country offers.

Thus Smith became one of only 290 bronze Albert Medal holders, for life-saving acts on land. The medal was later discontinued, and replaced by the George Cross. He is one of only four people to attain both the Stanhope Medal and the Albert Medal, and the only one whose heroic deed was on land, as opposed to at sea.

Traceable records about the Smith family after the event are few and far between. Possibly because of the injuries he received, or the help he needed to recuperate afterwards, by the time of the 1911 census they had moved back to the Peterborough area and were living at 63 Alexandra Villa, Old Fletton, just a mile or so from where they had come from originally. The then 25-year-old George was working as a Farm Labourer. I believe he was married to an Elizabeth Ding at Peterborough at the end of 1913 and they were both still alive and living at 45 Paston Lane, Peterborough at the time of the 1939 Register.

A previous owner of the medals had difficulty in finding out who owned the medals before him, although they came with a copy of the citation, which had been requested in 1973. There is also a picture, supposedly of Smith, which is part of a larger picture of all the Eastwoods employees, which has been published in the book “Wavendon As It Was”. The names of several of these men are recorded in that book, but Smith’s is not among them.

The medals came up for auction at Dix Noonan Webb in London on April 5th, 2006. They made £4600. The following is from their catalogue:

Lot 768: A unique Albert Medal, Stanhope Gold Medal group of three awarded to G. H. Smith, an employee at the Woburn Sands Brick Works in Bedfordshire, who was decorated for his bravery in rescuing a comrade from a kiln in October 1908 – the latter had ‘practically all of the skin burnt off the lower portion of his body up to the waist’, while Smith himself was ‘a good deal burnt about the hands and feet’

Albert Medal, 2nd Class, for Gallantry in Saving Life on Land, bronze and enamel, the reverse officially inscribed, ‘Presented by His Majesty to George Henry Smith for Gallantry in Endeavouring to Save the Life of a Comrade at the Woburn Sands Brick Works on the 24th October 1908’; Royal Humane Society, Stanhope Gold Medal, 1st type (George Henry Smith); Royal Humane Society, small silver medal (successful) (George H. Smith, 24th Oct. 1908), three of the applied obverse letters on the first replaced to make-up for loss of same through earlier wear, contact marks to reverse, otherwise very fine, the second and third with partially re-engraved naming details due to wear from edge bruising and both with contact marks, therefore about very fine (3) £4500-5000

Footnote: Only six A.M., Stanhope Gold Medal combinations have been awarded, the above described one being unique since all of the other A.Ms were for services at sea.

Ex Spink 29 March 1994 (Lot 1024).

A.M. London Gazette 23 July 1909. ‘On 24 October 1908, a workman at the Woburn Sands Brick Works, named Charles Griffin, was precipitated to the bottom of one of the kilns owing to the roof collapsing, and was imprisoned by hot ballast and bricks, the upper part of his body alone being free. His comrade, George Henry Smith, on hearing of the accident at once went to his rescue, but to effect an entry proved to be a work of some difficulty as the wicket through which the bricks were taken into and removed from the kiln was almost completely blocked. He succeeded, however, in reaching his comrade and in removing the bricks and ballast imprisoning the fallen man, who was eventually drawn up to the top of the kiln by means of a rope fastened under his armpits. Griffin subsequently died of the injuries he sustained.’

Royal Humane Society’s Silver Medal (afterwards selected for the Stanhope Gold Medal by the Society’s General Court in 1908), Annual Report, Case No. 36,435 states: ‘At 9.20 a.m. on the 24th October 1908, Charles Griffin was engaged in cleaning ballast from the top of a brick kiln at the Woburn Sands Brick Works, when part of the roof gave way and he fell into the kiln, being buried up to his waist in the red hot ballast. The kiln is about eighteen feet by twenty with a domed roof, on which many tons of brick earth are placed in order to retain the heat when the kiln is working. This ballast, when bricks are being burnt, gets red hot, and holds its heat for a long time. The entrance to the kiln is by a wicket at the bottom, through which a man can readily pass, but when the fall took place the barrow which Griffin was using blocked this opening, leaving a space of only about a foot across. Through this opening Smith made his way and dug away the hot earth from around Griffin, and in about fifteen minutes succeeded in getting him out in a fearfully injured state, when he was removed to the hospital, where he died some days later. Great risk was incurred from the danger of a further fall of the tottering roof, the intense heat, choking dust and poisonous gases with which the kiln was filled.’

I am much indebted to the new owner of the medals for getting in contact and supplying the detailed photos of the medals. Thank you!

Page last updated Oct. 2020.