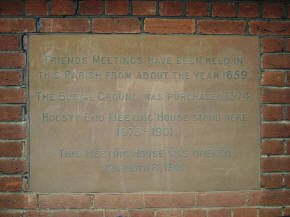

Richard Edward White, and the Hogsty End Friends Meeting House.

Text of a speech given by Mr. Vic Longhorn at the Millennium Community Festival event at Aspley Guise Common on 15th July, 2000.

About a year ago, while I was the librarian of the Bedfordshire Family History Society, I was handed the transcript of a diary to deposit in the collection. It was the diary of Richard Edward White, who was connected, on his mother’s side, to the powerful How family of Aspley Guise. The How’s were a Quaker family, and Richard Edward White, between the 1840’s and the late 1870’s, looked after the little Friends Meeting House at Hogsty End, or as it later came to be known, Woburn Sands.

The copy of the diary, given to the Family History Society, was a much edited version of the original, which is held at present by a descendant of the diarist, Mrs Katherine Slay. An expanded version of the diary is to be deposited in the Bedfordshire Record Office, but in the mean time, Mrs Slay has kindly given me permission to quote from it for this talk. Before quoting from the diary however, it would be useful to have a brief look at how the Friends Meeting House came to be established in Hogsty End. The Quaker movement was based on the teachings of George Fox, who formed a society called the “Friends of Truth” in 1648. He taught that the presence of the inner light in an individual should be the sole guide to that person’s faith and actions. His followers were called Quakers because Fox had once admonished a judge, and told him “he should tremble at the word of the Lord.” Quakers would have nothing to do with priest-led religion of any kind, but preferred to gather together in each other’s houses for silent prayer. They refused to attend the established church, or pay its tithes or rates. What most enraged the authorities about them however was their refusal to swear oaths upon the bible, and their belief that all forms of warfare and violence, even in defence, were sinful.

The whole fabric of British society rested on the ability to make people swear allegiance to the king, and also to swear on the bible to “tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth” in court. If people were allowed to refuse to take oaths, or fight when their king and country commanded them, it was feared that anarchy and invasion would be the result. Quakers were therefore looked upon as being almost as dangerous as Catholics, and persecution of them began, even under the Commonwealth of Oliver Cromwell. From the beginning, Quakers recorded the persecution or “sufferings” of their brethren. Returns of the sufferings of individual Friends throughout England were brought to the London yearly meeting, and recorded in the “Great Book of Sufferings.” There are 44 volumes of this book covering the years 1650 to 1844. In 1753, Joseph Besse published an edited version in 2 volumes, called “A Collection of the Sufferings of the People called Quakers“. It is from this edition that most of my information on the early Quakers of this area comes. In spite of these early persecutions, the movement spread quickly, and particularly along the Bucks and Beds border. The first mention in “Besse”, of Quakers in this area, is at Cranfield in April 1655, when Thomas Stubbs, James Lancaster, and Anthony Patrickson were taken out of a Friend’s House by the Constable, and locked up until the next quarter sessions. In the event, it was found that they hadn’t actually done anything illegal. However, as they had dared to come into the courtroom with their hats on, they were charged with contempt, and locked up for another month.

Several similar incidents occurred during the next few years, but the little community of Friends still increased. They met in each other’s houses in Woburn, Aspley Guise, Wavendon, and Bow Brickhill.

The persecution was stepped up in 1660 with the restoration of Charles II, and the re-establishment of the high Anglican Church. At the Bedford Assizes on 13th March 1661, we are told that fifty two people were in prison for refusing the oath of allegiance. They presented two papers to the Grand Jury; one explaining their difficulties with the oath, and the other, a declaration of their allegiance to the King, but stopping short of swearing the oath.

The following day the oath was again tendered to six of the prisoners, who all refused to take it. While they were speaking in their own defence, they were rudely interrupted, and taken away.

In 1670 a new Act of Parliament imposed heavy fines on all unauthorised preachers, and also on those who attended their meetings. One third of the fine was to be given to the informers, so there was soon a steady procession of Quakers, and other non-conformists, being brought before the Quarter Sessions. It was a nice little earner! Besse’s Sufferings tells us, “The vilest of men were thus encouraged to prey upon the conscientious.”

The Justice of the Peace for this area was Sir John Charnocke of Hulcote, and one of the first of our local Quakers to come before him was one William Albright of Woburn. This poor man was fined £20 for holding a meeting, at his house on the 15th May 1670. A further six people were find 5s each for being in attendance. Under this new act, an extra fine of £20 was to be paid by the preacher. However, as Quakers sat in silent prayer at their meetings, it was rather difficult for the court to decide who was the preacher. Justice Charnocke therefore decided that a further £5 should be levied on William Albright, £5 on George Galsey of Little Brickhill, and £10 on William Cooke of Bow Brickhill.

The Act also allowed for goods and chattels to the value of the fines to be taken from those who couldn’t pay. Accordingly, Galsey had his haycock taken away, and Cooke his cart, hay, and household stuff. William Albright was looked upon as the leader of the group however, and in August of that year, one Bumstead, a bailiff’s man, with others, came to his house with a warrant from Justice Charnocke. They broke open his doors, and took away timber, malt, oats, and other things to the value of £70. Even this did not deter Albright, who continued to allow meetings to be held in his house, until by repeated seizures, he was so impoverished that he had nothing left with which to pay the fines. In October of 1670 therefore, he was committed to prison.

Quaker meetings continued to be held in the area even after this blow, but the little group obviously felt they needed somewhere more permanent, and safe, for their meetings. In 1674 a small thatched cottage and garden in Hogsty End became available for £135, so the Friends all clubbed together and bought it. Joyce Godber, in her book “Friends in Beds and West Herts” tells us that the Cook’s of Bow Brickhill between them raised over £50, our old friend William Albright produced £10, and Mercy Cartwright of Aspley Guise £7.10s. In all, 31 Friends contributed, although ten of the subscriptions were less than £1. The smallest contribution being that of Henry Tansley, who gave 1 shilling.

The indenture for the sate of the land, which was drawn up on 5th December 1674, is in the Bedford Record Office. It names all the leaders of the group, and shows that although some of them were fairly substantial yeomen, many were just ordinary tradesmen. For such people to stand up against the law of the land for so long must have taken great courage. They were risking total ruin, social exclusion, and probably even prison for their faith. The indenture tells us that Richard King, of Aspley Guise, was the vendor of the land.

The purchasers were:

William Cooke of Bow Brickhill, yeoman

Edward Cooke of the same, yeoman

Thomas Harvey of Wavendon, yeoman

Henry Biggs of the same place, shoemaker

Francis Coleman of Woburn, ironmonger

Francis Ireland of the same place, gardener

George Gosley of Little Brickhill, shoemaker

and William Mather of Aspley Guise, yeoman

The plot was described as three roods of ground, more or less, as it is now divided by a staked hedge. The witnesses to the deed were Robert Page, Richard Hartwell, George Cooper, Mercy Cartwright, and Robert Gurney.

Why was the site at Hogsty End chosen for the Meeting House? Well, Richard King, the original owner of the land, later married Mercy Cartwright, so perhaps he was already a Quaker. The site was also very central for a group whose members mainly came from Woburn, Aspley Guise, Bow Brickhill, and Wavendon. It was also just outside the jurisdiction of Justice Charnocke. Although the group were on several occasions brought before the Buckinghamshire quarter sessions there doesn’t seem to have been such an enthusiasm for it on that side of the border.

The mention of Mercy Cartwright in the indenture provides a convenient bridge for us to pass swiftly over the next 172 years, and return to the diary of Richard Edward White. Mercy’s first husband was Isaac Cartwright and these two were the great, great, great grandparents of Richard Edward White. Richard’s diary starts in 1846, but in a piece written in 1860, Richard traces his family history, and describes his early life. He tells us that Isaac Cartwright was a barrister in the Inner Temple, London, who retired in later life to Aspley Guise. We are told, Isaac’s wife Mercy (unfortunately her maiden name is not given) was the daughter of the governor of one of the seven provinces of Holland. Isaac died in 1666, and Mercy later married Richard King, at the Hogsty End Meeting House.

Ann Cartwright, the youngest child of Isaac and Mercy, married Thomas How of Aspley Guise. Richard Edward White traces the How line of his family back to a Richard How who married Joan Hudson at Aspley Guise in 1571. The How’s were substantial land owners in Aspley Guise, and he tells us that his great, great, great, great grandfather William How commanded, and maintained at his own expense, a body of horse on the side of Charles I during the Civil War.

Richard Edward’s mother was Mariabella How of Aspley Guise, who married Gabriel Gregory White, a coal merchant and ship owner of London. They too were married in the meeting house at Hogsty End, but lived in London. Of his own early life, Richard tells us, “I was born on the 5th of November 1799 in the parish of St John’s Horsleydown, Southward At the age of nine, I went to reside at Aspley on a visit, as a change of air was recommended as a means of gaining strength”. He stayed with his uncle, Richard Thomas How, who became very attached to the boy, and kept him at Aspley until he went to be an apprentice at the age of 15. While at Aspley, he was sent to Jeremiah Wiffen’s school at Woburn. Jeremiah was also a staunch Quaker, and regularly attended the meeting house at Hogsty End.

At the age of 15, Richard Edward White was sent to Kendal, in Westmorland, to be apprenticed to a draper and calico manufacturer. However, he never became a draper after serving his time, but took up farming near Cockermouth, and in 1829 married a girl from that area named Maria Douglas.

In 1830, the couple and their two daughters, moved south to a furnished cottage at Henley on Thames. Two years later they moved to Cranfield, and it was here that their first son, Richard How White was born. In the autumn of 1833, there was another move to How End Farm in Houghton Conquest.

On 12th December 1835 Richard Thomas How, the uncle who had so doted on the diarist as a child, died. In his will he left Hayfield Farm in Aspley Guise to his beloved nephew Richard Edward White. Richard and his family moved into the farm in the summer of 1836. The diary opens ten years later on 1st January 1846 with the rather terse entry “Attended Woburn Fair“. Luckily, the subsequent entries are a little more expansive, and soon show that Richard Edward White was a keen amateur meteorologist, and naturalist.

The pages are full of his observations on the weather, the changing seasons, and the flora and fauna of the local countryside. On 28th February 1846 he observed “The weather has been remarkably mild most of the winter; very little snow or frost; vegetation is very forward; the flowers are many of them in bloom; the thorn leaves in the hedges are fully out in many places and. the bramble has not shed it’s leaves this winter. For some days we have not had a fire in the parlour, as we are quite warm enough without one; an extraordinary circumstance in February.”

On 3rd May 1847 he says “Today went with Richard Heppens to view some of the Duke of Bedford’s nurseries of forest trees, and also some of the oak woods where the men have lately commenced peeling the oak trees in the earliest situations“. This entry seems to indicate that cork was being commercially harvested on the estate, or at least they were experimenting with it.

Richard Edward had a great love of trees, which is shown in the way he carried out his duties of caring for the plot of land around the Friends Meeting House. On 31st January 1848 he reports. “My son Richard How and I, set four Scotch pine trees in the ground in front of the Meeting House at Hogsty End, and a yew tree at the south end of the line of graves belonging to our family. One had been previously set at the opposite end by Benjamin Wiffen and myself in 1839, six years after I interred our first child that died“.

A late nineteenth century photograph of the Meeting House shows the Scots Pines. There are now only two left. The yew tree planted at the same time is still standing against the wall on the Hardwick Road side of the graveyard. On the opposite side of the graveyard the tree planted in 1839 is also still standing. So, it is still possible to identify the row of How family graves.

The 1840’s were the boom days of railway building, and the spread of the national rail network, brought about a corresponding boom in travelling preachers of all denominations. The Hogsty End Meeting House seems to have attracted quite a few of these missionaries, and as the Quakers were not so male dominated as most other denominations, many of the preachers were women.

On 14th August 1849 Sarah Ord of Preston in Lancashire came to speak to them. She seems to have had quite an effect on Richard Edward, as this entry gives us the first indication that his mind was deeply troubled. She spoke for about an hour upon various religious subjects. Then, soon after she had taken her seat, she knelt down and offered up a beautiful prayer for about a quarter of an hour. Ending with the wish that “those that were walking in spiritual darkness might hold on their way without fainting, until the Almighty might cause the light of his countenance to shine upon them again.” Richard comments, “The latter part was applicable to my state, as I have been long without the light of God’s countenance shining upon me“.

The problem came from deep within his Quaker faith, which said he should always consult with God before making any major step in his life. He hadn’t waited for God to speak to him, and give his blessing on the move into the farm he had inherited from his uncle. He had just done it without any hesitation. Now he felt that God was telling him, he should give up the farm, and move elsewhere as a punishment. He doesn’t seem very pleased with the place he felt had been chosen for him. On 11th November 1850 he writes, “The prospect of our being likely to remove from hence to Ampthill to live is a gloomy one to me, as it is not the place I have for some years expected we should reside at when we left Hayfield”.

The family left Hayfield that same month, and the farm at Aspley seems to have been rented to his brother in law, Somers Douglas. This is not mentioned in the diary, but Douglas and his family are living at Hayfield at the time of the 1851 census. The sacrifice of merely moving out of the farm does not seem to have been enough to quell Richard Edward’s conscience However. On 15th March 1854 he is still troubled, and notes in his diary, “I knew not at the time it occurred, that it was contrary to the will of God, that I and my family should remove from the place we were then residing to Hayfield. A sacrifice is required of me for this trespass committed unwittingly, and that is, to part from the farm by selling it: and I trust by doing so, my sin may be forgiven me”.

However, although the farm was offered for public sale, no buyers were disposed to offer the market price for it, and in the end he sold it to Somers Douglas for £7000. He writes “I feel thankful in having offered it as a sacrifice, as a trespass offering.” For the next few years the only mention of Aspley Guise or Hogsty End in the diary, is when there is a family or friend’s funeral. There was a Friends Meeting House in Ampthill, but so presumably Richard Edward and his family attended there for worship. Many of his entries at this time describe walks taken in the Ampthill area, and also some local customs, and significant events. We are told for instance, that the custom of laying oak boughs at the doors of houses on the 29th of April continued in Ampthill during the 1860’s. It commemorated Charles II hiding himself in an oak tree to escape from Cromwell’s troops after the battle of Worcester.

On the 10th March 1863 he describes how Ampthill celebrated the marriage of the Prince of Wales. The shops were all closed for the day, and a collection of money having been made, “All the poor above twenty years of age had roast beef, plumb pudding, and a pint of ale, in tents before the British School House. The young people between the ages of seven and twenty had tea. The day has been a very fine one, and all classes appeared to enjoy it. Several flags were displayed, and at some houses evergreens etc, have been as tastefully arranged as people knew how. In the evening at many of the houses an illumination took place, and the streets were paraded by several of the inhabitants to a late hour”.

However, he still loved the old meeting house at Hogsty End, and on 8th October 1860, he writes, “My son Gregory and myself have been correcting the plan of the grave yard at Hogsty End, and have marked on the plan the site of the three old Scotch pines planted by my great grandfather Richard How in the year 1745”. At the same time he had the holly hedge set surrounding the ground, both at the front, and the back of the Meeting House. “We have also marked the site of the younger pines planted by his grandson, my uncle Richard Thomas How: the yew tree on the north side planted by me in the autumn of 1839, and the one on the south side planted in January 1848, by me and my then eldest son Richard How, at the same time we planted the four Scotch pines in the ground at the front of the Meeting House. So the Scotch pines growing there have been planted by Richards of four different generations”.

On 13th November 1862 he records, “I walked to Hogsty End and attended the weekday meeting. Only Benjamin B Wiffen was present besides myself. He has frequently to sit alone, as there are only two members who now attend the place of worship, and Lucy How, the other one is frequently not there”. The poor attendance on this day must have had an affect on Richard, as his attendance at the meeting house is mentioned more often in the diary from now on. It may have been about this time that he became the official caretaker of the building.

Certainly from this time on, he seems to walk from Ampthill to the Meeting house at Hogsty End and back, almost every Sunday, and sometimes during the week as well. Even at a time when people walked much more than they do now, this surely must have been quite unusual for a man in his mid sixties. On some occasions detours made the walk even longer.

On 18th April 1864 he records, “This morning after breakfast I set off to walk to Aspley: after making two calls in the village, I proceeded to our graveyard at Hogsty End. And by measuring, corrected some of the points in the plan my son and I made two years since. After satisfying myself in the Burial Ground, I went into Aspley Wood and walked nearly all round it: I went along the old road formerly used from London to the North, that was in existence probably some hundreds of years before the turnpike roads and stage coaches were thought of. It is a deep hollow in the wood, near and running parallel with the present highway. After making a call in Aspley village I proceeded via Lidlington in a circuitous track to Ampthill to a late dinner, after having been upwards of eight hours on foot without having sat down. The distance was not great, probably not much more than twenty miles. It has been a fine bright day with a cool breeze, and I enjoyed the walk, as it was performed without my feeling almost any fatigue”. At this date he was nearly 65 years old.

It is still possible to see evidence of the work of Richard Edward White in the little plot of land around the present day library. As we have already seen, he planted many of the trees in the front, and at the back of the building. He was also instrumental in getting the gravestones in the burial ground erected. For two hundred years, Quakers had refused to have gravestones in their burial grounds, considering them to be a vanity. In 1850 however, the London yearly meeting decided that graves might be marked by plain stones, provided that all that was marked on them was the name of the deceased, and the dates of their birth and death.

For many years no action on this decision was taken at Woburn Sands. However, Richard Edward White had a great attachment to his ancestors, and he was related in one way – or another to most of those buried in the little grave yard. On the 3rd November 1864 he writes, “For the previous twelve days I have been frequently engaged in superintending some workmen employed on the Friend’s Meeting House and premises at Hogsty End. All the graves for which I can ascertain the names of those interred, I have had mounded up. There are 68 graves, containing 70 bodies. After considerable enquiry and research, I have not been able to identify more than these. The remaining inequalities on the ground I have had levelled, in order that there should not be any mistake in ascertaining from the plan my son Gregory has made, the places where the bodies have been deposited. The oldest I can accurately find out is my great, great, great Grandmother Mercy King (was Cartwright) in the year 1704”.

I had assumed that the graveyard plan drawn up by Gregory and Richard Edward had not survived. Mrs Slay had told me that Bedford Record Office has a list of all those buried in the Hogsty End Burial Ground. It is in Richard Edward’s handwriting, and gives the names of the deceased, their date of burial, and age. It also numbers the graves.

While I was in the Record Office obtaining this copy, I had a browse through the huge catalogue of Friends Records. I noticed in another section of the catalogue there were two plans of the Hogsty End Burial Ground listed. One was dated “after 1860”, and the other 1970. This is a copy of the 1860 plan. In the bottom left hand corner is a list of all the trees, the dates they were planted, and by whom, as described by Richard in his diary. The handwriting on the plan compares with that on the list, which is known to be that of Richard Edward White. I feel sure therefore that this is the plan drawn by Gregory White, with the names filled in by his father Richard Edward White.

On the 27th November 1867, Richard Edward tells us, “A letter has come from Theodore Harris informing me that at the last monthly Meeting held at Leighton on the 8th of this month, I was appointed with him to arrange for the putting down of some gravestones, which the monthly meeting permitted from my request to do so. I therefore shall ascertain from the relatives and friends of some of those interred in the burial ground at Hogsty End, whether they are disposed to be at the expense of having tombstones set up at the head of any with whom they are connected”.

On 14 March 1868 the work began, and he records “I have had the first tombstone put down, and shall have a number formed like it, of red Mansfield stone. There will be no paint on them: the writing will consist of the name, date of birth, and that of the decease of each individual. The rows of graves behind the library can still just be seen, as mounded up by Richard Edward’s workmen in 1864. Many of the gravestones he took so much trouble over to research, and have erected, in 1868, are still there. I had thought that the line of stones up against the back wall had been moved there for ease of mowing, but the plan now shows that they are actually in their original places”.

As we have seen, by the 1860’s the congregation at the little Meeting House (never very numerous at the best of times) had declined until there were hardly enough of them to keep the place going. In 1865 the last monthly meeting was held there.

Declining numbers, and inclement weather, were not enough to stop Richard Edward walking from Ampthill to pray in his beloved meeting-house however. On 11th December 1870 he writes, “Although the ground was covered with snow, and it was cloudy, yet it was fair, and I have enjoyed my quiet walk alone to Woburn Sands Meeting House and back. No one else was present in the building during my sitting for an hour or more for the purpose of divine worship”.

Christmas day that year was on a Sunday, and he writes, “This has been a fine winter day, although rather misty. I had a clean and pleasant walk to Woburn Sands Meeting House, and met my two youngest daughters, who had come from Hayfield. The seven and a half miles were travelled by me in about an hour and three quarters: a less time than I have walked the same distance for some years. To God the praise belongs for imparting to me the ability to journey so fast, and without fatigue, though now in my seventy second year”.

A year later however, the day he must have been dreading finally came, and on the 12th November 1871 he writes, “I received a letter yesterday from Richard Littleboy stating that the committee of the Monthly Meeting have come to the determination to close the Meeting House at Hogsty End for public worship after today, in consequence of the two members residing at Aspley being from ill health etc., so often unable to attend. My judgment coincides with the decision, although my feelings would incline that it should be longer kept open as a constant place to meet at weekly, for religious worship. It was established by Mercy Cartwright (one of my ancestors) and her second husband Richard King, with several other Friends a hundred and ninety eight years since, and has always been attended by ancestors or relatives of mine to the present time. And for nearly a third of the period by myself, although not continuously. My feelings of sorrow felt the change too much to allow me to go to Woburn Sands today, and so I have ended attending on an anniversary of my birth”. It had been his 72nd birthday on the previous Sunday.

From now on the Meeting House was only opened for funerals and the occasional special meeting, and in May 1872 Richard Edward handed over care of the Meeting house to his successor William Chantler of Newport Pagnell. One of the funerals the meeting house was opened for after this was that of Richard’s beloved wife Mary, on 29th September 1876. She had been confined to her bed with dropsy for four and a half years.

There are two further entries in the diary that mention the Hogsty End Meeting House, and they show that Richard was now looking back over his life, and probably contemplating his own mortality. The first of these entries also shows there was still something of the little boy in him. Wednesday 27th July 1877, “After cutting on the fine holly tree in the hedge at the north side of the burial ground the initials of my name and date, I then entered the meeting house and sat down on the old family seat, so often used by six generations of my relations, and occasionally by those of my junior descendants”.

On the 26th June 1879 he writes, “With a mournful pleasure I walked about our family graveyard at Woburn Sands, and for a time pondered beside the mound covering the remains of my late dear wife, and of the felicity she was now enjoying. I then went into the old Meeting House, and took my seat on the identical spot on which it was my lot to sit beside my uncle Richard Thomas How above three score and ten years since”.

During his life Richard Edward White had seen many changes in Aspley Guise, and Woburn Sands. In 1874 he says of Woburn Sands, “When I was a boy, so far as I can recollect, the hamlet consisted only of about seven or eight houses with some old farm buildings. Now there are between seven and eight hundred inhabitants, and a new parish church, Wesleyan and Primitive Methodist Chapels, with our old Friends Meeting House that was erected above two centuries ago”.

Of Aspley Guise in 1877 he writes, “Places are considerably altered in the life of a person. When I was a boy, now nearly seventy years since, Aspley Guise was considered a very pretty village from the number of rustic thatched cottages, and some antique looking buildings then standing: but as the principal number have been pulled down and common looking red brick and blue slate creations placed on their sites, and some others modernised to imitate those in towns, this village has suffered much in rural beauty and picturesque appearance”.

Richard Edward White died on 17th December 1879, at his home in Woburn Street, Ampthill, with his daughter Maria in attendance, just over five weeks after the final entry in his diary. He was buried in his beloved graveyard at Hogsty End. His tombstone lies with that of his wife, half-covered with soil and moss, at the far end of the row of stones by the bank on the eastern side of the graveyard. Although Richard Edward’s plan had shown that the rest of these stones were in their original place, I wasn’t happy that this was so for his own tombstone, and that of his wife. A look at the second plan, drawn in 1970, which also listed the names of those buried, showed the true position of their graves.

Richard had his wife buried at the far end of the How line of graves, but leaving a space for himself to buried between his wife and his earliest known Quaker ancestor, Mercy King (formerly Cartwright).

The death of Richard Edward White could well have been the end of Quaker activity in Woburn Sands. However, his two daughters Maria, and Mary Frances, who lived in Ridgmont, continued to attend regularly for silent worship for the next 28 years. During this period there was a population explosion in Woburn Sands. In 1896 a Friend from Northampton started to hold regular meetings in the old Meeting House. The congregation began to grow again, and very soon the old meeting house was too small to accommodate them all.

In 1901 it was pulled down, and a new meeting house and school rooms built at the cost of £1,700. The opening was celebrated by a public tea, attended by 200 people. Unfortunately this new enthusiasm did not continue far into the new century, and in 1948 the new meeting house and school was closed and became the Woburn Sands Public Library.

It is easy to be wise with hindsight, and of course we cannot preserve every old building. However, it must be a cause of regret that this lovely old building, erected in 1674, that had served it’s congregation so well for 225 years, was swept away with seemingly little regret. Had it survived, it would have been the oldest Quaker meeting house in Buckinghamshire. Chesham, which is now the oldest, was erected in 1682, and the famous meeting-house at Jordans was not built until 1688. It is interesting to speculate, that had the old building not been demolished, Woburn Sands could now have rivalled Jordans as a place of Pilgrimage for members of the Society of Friends.

© Vic Longhorn 2000

Page last updated Dec. 2018.