THE FENNY STRATFORD RAILWAY AND COACH DISASTER OF 1925

Tragedy befell a group of Sandites who on their way back from a lecture at the Wesleyan Chapel in Bletchley. Arthur Parker researched the disaster, and his notes are reproduced below. Following this, there are additional details from the Ministry of Transport Inquiry Report, and some further related stories from The Times.

“We read of railway and mining disasters, shipwrecks and modern bombings, and perhaps find it just interesting reading, but one cannot realise the sense of grief and sorrow surrounding such an event until it happens in your own midst. For more than a week and until after the funerals Woburn Sands was a place numbed with horror and anguish; no one dared to stop and speak to another in the street, nor to enter a shop, for the other person was bound to be someone closely connected with one of those killed. Indeed one tradesman told me it seriously affected his Christmas trade. But to give some details of what happened I cannot do better than quote extracts from the Bedfordshire Times, which carried a full report:

The Fenny Stratford Disaster. Eight killed; Four seriously injured.

In pitch black darkness on Monday night [7th December] tragedy, swift and sudden, descended upon a happy party of Woburn Sands and Aspley Guise people on their way home by motor coach from Bletchley, after a religious meeting.

It was one of the most terrible accidents that have occurred in this County for many years, and probably one of the worst motor accidents on record. The motor coach ran through the gates of the level crossing at Fenny Stratford Station at the very moment that a train was approaching. The train crashed into it and the engine overturned, smashing the coach to pieces, and causing personal injuries which have resulted in the death of eight people, very serious injuries to four, and less serious hurts to three others. No one in the train was hurt.

A list of those killed is as follows:

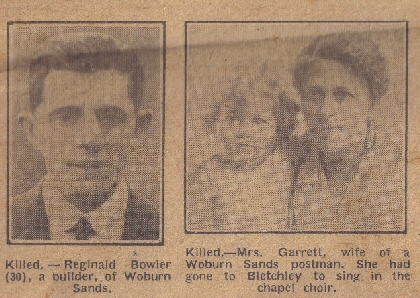

- The Revd. William and Mrs Nightingale, Woburn Sands, late of Nova Scotia.

- Miss Kathleen Davidson., Stevington, a school teacher at Woburn Sands

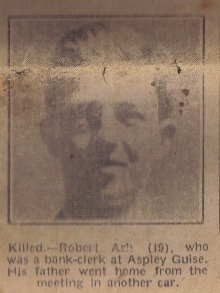

- Mr Robert Ash, Aspley Guise.

- Mrs Tom Garrett, Woburn Sands.

- Mr Reginald Bowler, Woburn Sands.

- Mr William Woods, Aspley Guise.

- Miss Mary Stone, Woburn Sands; [died in hospital]

The following are in Bedford Hospital, in a critical condition:

- Mr Frederick Griffin, Woburn Sands [he died later].

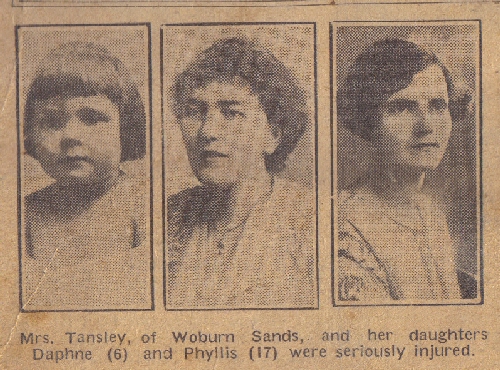

- Mrs Tansley, Woburn Sands, and her daughters, Phyllis (17) and Daphne (6).

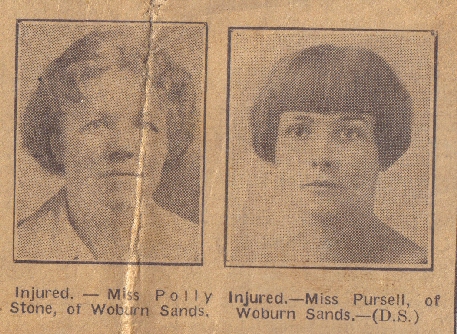

- Mr Nelson Payne, Cross End, Wavendon (not serious).Slightly injured and at home are, Miss Annie Parrott and Miss Florence Pursell. The only occupant who escaped uninjured was Mr A. J. Porter, Woburn Sands.

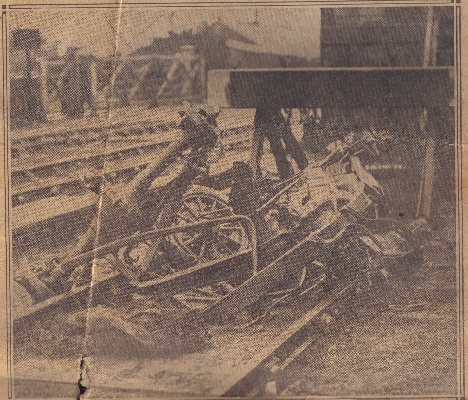

The Revd Nightingale came from Lancashire to live in Woburn Sands only a year before. He had spent many years in Nova Scotia, and named his bungalow ‘Adanac’. Mr Ash, 20, was the son of the Aspley grocer, and worked in Barclays Bank at Bedford. Mrs Garrett was the wife of Tom, the postman, and was a Kempston girl; having a good voice, she had been singing at the Chapel a few minutes earlier. Reg Bowler was the son of the builder, Thomas, and had been a prisoner of war in Germany. Miss Davidson, who came from Stevington, had been living with the Tansley’s, while teaching at the local primary school. Billie Woods, 16, was employed in Mr Ash’s grocery shop at Aspley. Mary Stone, until his recent death, had been keeping house for her father. Mrs Tansley was the wife of Aubrey of the china and hardware shop, who ran an oil round. People veiw the scene as the engine is cleared away.

Nelson Payne was a Wavendon boy, 23 years old, and had been driving for Rice for about 5 years. Fred Griffin lived in Aspley Hill, and was the taxi driver. A. J. Porter had not long since come from the Northampton country to take over Ash’s grocery business, but was living in a new bungalow in Newport Road, not far from the Nightingales.

Tuesday was a day of lowering skies, moaning winds and spattering rain, after a frosty weekend. All day, at the scene of the accident were crowds of people watching the repairing of the track and the remains of the coach, only two heaps of tangled ironwork and splintered wood. The locomotive, though overturned, was not badly damaged.

The party of fourteen had gone from Woburn Sands to attend a lecture at the Bletchley Wesleyan Church by the Revd. Dimsdale Young, and with them were the two employees of J. Rice & Son, the proprietors of the vehicle. The return journey was being made through Simpson and Wavendon in order to drop Mr Porter and the Nightingales at their doors in Newport Road. The roads were very muddy and slippery. Owing to the arrangements the gates have to be opened before the signal can be lowered for a train to come through, and the gates cannot be moved until the signal is again placed at danger.

The coach reached this point about 8.30, when the gates were closed in order to allow the train from Cambridge to pass. The red danger light was showing as usual but for some reason, the coach failed to pull up. The brakes were applied but it crashed through the gates and fouled the metals. It was about three seconds after this that the train crashed into the car carrying the greater portion of it some distance down the line. How The Times reported the accident.

The crash aroused the whole neighbourhood, and the cries of the injured brought a large body of voluntary workers to the scene, but for quite a long time, very little could be done owing to the darkness. The only lights available were the torches brought from the police station across the road, porter’s lamps, bicycle lamps, etc. and it was by means of this feeble illumination that the doctors and ambulance men, who had been run down the line from Bletchley, began the work of attending to the injured. All available splints were found to be insufficient and others were improvised from the shattered woodwork of the coach. All through the night work went on, the injured being convey to Bedford County Hospital by a special ambulance train. It was late on Tuesday before the derailed engine was removed, and, except for the smashed gates, the track resumed its normal appearance.

The County Hospital was notified of the time the ambulance train was expected. The Borough ambulance, kept at the Fire Station, was requisitioned, and was manned by the Brigade Ambulance Corps. Four women were taken by it; one patient was taken by the police ambulance, and one by the railway ambulance, Whilst Payne made the journey in a taxi and all had arrived by 11pm. All honorary surgeons were fetched and the operating theatres were in use all night.

The bodies of the dead were removed to Fenny Stratford Police Station, where there were distressing scenes owing to the difficulty of identification; jewellery and laundry marks had to be used.

It was reported that there appeared to be some confusion as to who was driving at the time. There is a long account of what happened by Mr Porter, who had a marvellous escape and other stories from Miss Parrott and Miss Pursell. Robert Ash had been expected to return by taxi with his father, who had chaired the meeting, but preferred to be with the young people in the coach. A Mr Hinton, friend of Mr Ash, who lived not far from the Porters and Nightingales, had intended to go to the meeting but was persuaded against it at the last moment, by his wife.

Long column space is taken up with the details of the personal life of those concerned, and it states a relief fund had been opened by Woburn Sands Parish Councils headed by a donation of twenty guineas from the Lord Lieutenant, the Marquis of Lincolnshire. It was also front-page news for the dailies, many of which showed photos of those killed and of the scene of the disaster. The headline of the Daily Mail told of its free insurance scheme, from which the family of the Revd Nightingale would benefit in the sum of £2,000, £1,000 for him, and £1,000 for his wife, for which he had previously registered.

Mr and Mrs Nightingale were buried at Woburn Sands on the following Friday, Ash and Woods at Aspley on Saturday following a service at The Courtenany Memorial Hall. Mrs Garrett and Reg Bowler were buried at Woburn Sands on the same day, following a service at the Wesleyan Chapel, and similarly, on the Monday, Miss Stone.

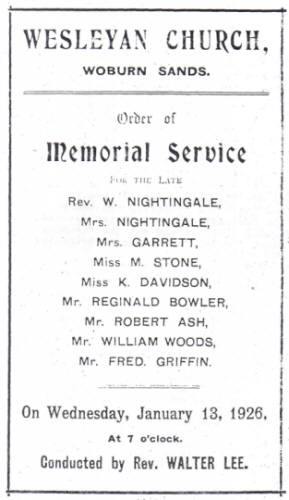

On Wednesday, January 13th 1926 a Memorial Service was held in the Wesleyan Chapel at seven in the evening, and at all these services there was a large and representative congregation, much detail being included in the newspaper reports.

The inquest was held after a delay of three months, the coroner Mr R. G. Walton of Leighton Buzzard. One of the most important facts disclosed by the evidence, was that at the time of the accident, the coach was being driven by an employee who had been definitely forbidden by the owner to take the wheel because he was not confident of him. One of the survivors, Mr Porter, himself a driver, expressed the opinion that the coach was driven too fast from the start of the journey, and he confessed to feeling nervous.

The first witness was Mr Joseph Rice, owner of the coach; he said it was a ton chassis with a body capable of carrying fourteen persons. He instructed Griffin to tell Payne to drive the vehicle; Griffin drove a taxi and he would not trust him to drive a coach. Griffin, however, accompanied Payne. He would not allow him to drive as he had no experience of driving coaches. He thought it best to warn him not to drive. Payne was a first-class driver.

Nelson Payne, after caution by the Coroner, said, when told to take out the coach he replied that he had a cold and did not feel fit to drive, and was told Griffin could go with him, and he therefore took it for granted that Griffin could drive. He drove all the way from Woburn Sands, and for the journey back; he considered it was safe for Griffin to drive, and that he drove well. There was a young woman sitting between him and Griffin, she was a stranger to him and there was no fooling about. They were both sober.

There was no time to tell Griffin to stop when he saw the gates were closed. He saw the red light and heard someone shout that there was a train coming. He could not remember whether the brakes were on or not; the speed was about ten miles an hour. He stated Mr Rice was aware that Griffin had driven the charabanc; the road was greasy and there was rain on the windscreen. He did not hear the approach of the train.

Sidney Cook, of Woburn Sands, said that two days before, when he was travelling in the coach, Payne had said the brakes were not any too good. Souster, the signalman on duty, said there was no sign of a vehicle coming when he closed the gates; the coach came along, crashed through the gates, and was immediately struck by the passing train.

Evidence was also given by Mr Leonard Rice, son of the proprietor, and a qualified mechanic, on the condition of the vehicle. Two other independent garage proprietors also gave evidence of the satisfactory condition. Only the driver of the train was called upon on behalf of the railway. Miss Pursell, Mr Porter, and Mrs Tansley all spoke of their own experience. Two independent witnesses said they thought the vehicle was travelling too fast, but not more than 18 miles an hour, and the barmaid at The Park Hotel gave evidence of the drink consumed, and that the men were sober. Wreckage of the bus, from The Daily Sketch. The event made the front page.

Summing up, the Coroner asked the jury to consider three questions; what was the cause of death of these six persons, who was responsible for their deaths, and whether the conduct of the person causing the deaths was grossly negligent or not.. If their answer to the latter question was in the affirmative, the verdict would be one of manslaughter against that person, and if it was in the negative it would be one of misadventure or accidental death. With regard to the first point the evidence was so overwhelming that there could be no doubt If they were satisfied that the railway gates were across the road in ample time not to interfere with the progress of the driver of the charabanc that was sufficient so far as the Railway Company was concerned. As a matter of fact no negligence on the part of the Railway Company had been suggested. On the second he directed them that no criminal negligence attached to Mr Rice or to his son. Mr Walton gave further instructions on the legal position of Mr Payne and Griffin, also as to what constituted criminal negligence.

The jury was absent for fifteen minutes, and on their return, the foreman, Mr Davey, announced the verdict as follows: Cause of deaths, accidental. Person responsible for the deaths, the driver, Griffin, the accident being caused by an error of judgment on his part. A rider was added to the effect that the jury considered that, in view of the present traffic, the gates were not sufficiently lighted.

I am indebted to Mrs Markwell, sister of Reginald Bowler, for the loan of the news cuttings from which the above has been taken. There is no record there of the funeral of Griffin. The Tansleys took some time to fully recover from their injuries, but were eventually restored to good health. The other four persons were soon about again but the shock took time to wear off.”

To Arthur Parkers detailed account above, a few facts can be added from a book called Town of Trains, by A. E. Grigg, 1980. The party were returning from the Freeman Memorial Chapel when it was struck by the 6.15 passenger train coming from Cambridge, a 2-4-0 Jumbo class ex-LNWR engine no. 170 named ‘General’, driven by Tommy Bazeley with George Atkin as fireman.

In fact, the engine was not overturned, and only one carriage was derailed. Help was on the scene so quickly because an ambulance class was underway at Bletchley Railway Coffee Tavern. The rescuers arrived to a terrible scene of decapitated bodies and wreckage. The bonnet of the charabanc was found 50 – 60 yards down track.

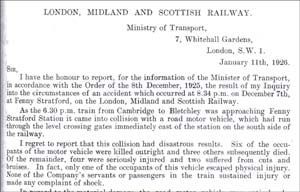

It seems amazing to our modern-day minds that a crash between a bus travelling at 10mph and a train slowing for the Station at about 10 – 12mph could has caused such loss of life, but the unstoppable weight of the train and the relative flimsiness of the coach meant it was reduced to matchwood on impact. The official Ministry of Transport Inquiry was held by Major G. L. Hall, who finalized his report on January 11th, 1926. A detailed review of the arrangements of lighting at the level crossing, and also the procedures on signaling were made, and nothing found amiss. The history of the charabanc was examined; it was a standard 1923 Ford 1-Ton motor coach, with a Ruckstall axle to provide four speeds in place of the usual two. It had a 14 seater body, with a hood, which was up at the time of the crash. There was a front windscreen, but no side curtains. Even the brake linings were examined and found to be in good condition and repair. It had been used to take locals to the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley.

The signalman had shouted a warning from the signal box, but could only watch as the coach plowed into the barrier, and was almost immediately hit by the train. Major Hall commended the signalman and train staff for the help they had given in the aftermath. In his opinion, it was an error on the part of Griffin, and quite possible that the wheels had locked up on the muddy, greasy road, and they had probably skidded into the barrier. He also remarked that it was advisable not to have passengers sitting on the same bench seat as the driver in a public hire vehicle, as it could be distracting.

The Times reported the accident on December 9th, with pictures. It gives a graphic description of the accident and those involved. Griffin had to have a leg and one hand amputated before he died in hospital. It also reported on Major Hall’s Inquiry on 12th December, when the Press were most upset that half way through the witness statements, the Coroner sent word to Major Hall that the Press should be excluded from the proceedings. They were particularly upset that Hall said only Railway employees would be heard that day, and then later they discovered that Rice, the owner of the coach and also one of the survivors had also been heard.

The report on the Coroners Jury was made on March 16th, 1926. A verdict of Accidental Death was returned, citing Griffins error of judgment. However, this was not the end of the story, as a small piece in The Times of 5th August 1927, records that Florence Purcell, one of the injured, successfully sued J. Rice for negligent driving. She won £21 in damages, which is about £1000 today. The case was first heard at Leighton Buzzard, where the judge decided there was no case to answer, but on appeal, it was re-heard at Luton. When the verdict came in, it was stated that a number of other cases would now follow.

Page last updated Jan. 2019.