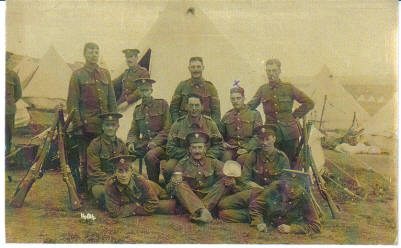

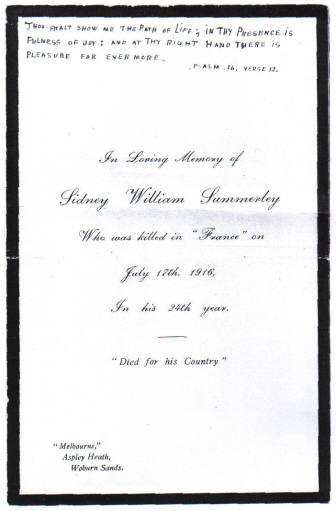

LANCE CORPORAL SIDNEY WILLIAM SUMMERLEY

Died 17th July 1916

No. 4667 of the Royal Fusileers, City of London Regiment.

Born: Woburn Sands, 22nd August 1892

Resided: Woburn Sands

Enlisted: Hammersmith

Son of John Paul, a carpenter, and Sarah Ann (nee Hudson). They were living in Melbourne Cottage in 1910, a house on the junction of Church Road and Sandy Lane, Aspley Heath.

The text of a letter reprinted in the North Bucks Times, 4th January, 1916:

“Lance Corporal Sidney W. Summerley of the 13th Battalion Royal Fusiliers, sends his parents a vivid description of night work in the trenches: Imagine a cosy ‘dug-out’ made of timber, half the building in the ground ‘Chatsworth House’ to be, the men sitting around a roaring log fire, smoking or reading, and some perhaps thinking of the dear ones at home. Outside the rain is falling fast, the water rushing past the door in small streams; all the roads and paths are thick with mud, churned up continually with the marching of troops and the wheels of wagons. ‘Will the rain never cease?’ We are to turn out at mid-night and take hot tea to the fellows in the trenches. They need it, too. The nights are very cold, and with the additional rain the men get chilled to the bone. At last the hands of the watch point to the hour of midnight, and amid sundry longing glances at the fire and beds, the party turns out. What a night, inky blackness, the dark lowering clouds in tune with the general condition of things. ‘Well, boys, let us get off and take the stuff up,’ says the Corporal in charge, so off they go to No. 1 Company cook-house, and there find the cooks busy filling petrol cans from the tea urns.

Here a little explanation is necessary. During the day, stew or tea is carried up to the trenches in urns holding 56 pints, on a stretcher, by two men, but at night this is impossible, as if the leading man falls in one of the many holes it would all be spilt, so petrol cans are used, holding two gallons each. After priming themselves with the homely beverage, the party moves off, each man carrying two cans. Passing through the sleeping village, they reach the communication trench, and start on the mile walk in the ground. The stronger get on ahead, and the Corporal brings up in the rear. Just in front of him are two men struggling along. In addition to the cans, each man carries his overcoat, rifle, ammunition and waterproof sheet – something to keep the rain off, and something to keep the Germans off. The last man, named Iggolden, says to the next one, named Penfold, a rather small man from South Ealing, ‘We rely on you to protect us should the Prussian Guard meet us.’ Penfold turns round to reply and immediately steps in a deep hole full of water. Poor Penfold almost disappears. He hangs on to the cans and is struggling to get out. Iggolden gives him a helping hand, and they slip and slide in again, bursting with laughter. ‘Halt, hands up;’ here is a sentry who wants to know our business. Having given him the desired information and some tea, the party proceeds on its way.

About half the distance has been accomplished by now, and the party turns down one of the side turnings; now ‘the band begins to play.’ Just imagine a trench with the bottom absolutely covered with water, hiding all the holes and drains. Perhaps in one step a little mud is there, the next one goes in with a splash, and water up to the knees and gradually the end of the trench is reached. It is worth the trouble to see the fellows’ faces brighten up when they see the midnight tea come up. Then the party turn their faces homewards to scrape the mud off their clothes and sleep the sleep of the weary. So ends what is an every night incident, only this one was in particularly trying conditions. The shades of darkness are just beginning to cover the earth, posts and bushes show up in weird forms over the grass land, a mist is rising up in the valley, and very soon all will be wrapt in its white clammy folds. In the trenches the troops are waiting in their places, ready for any event, because this is the time for the enemy to try an attack. Time slowly passes, and everything is still quiet. ‘No, they are not going to worry us much tonight,’ is the thought that runs through the mind so at the appointed time the night sentries are posted, and the men not on duty get what rest they can near at hand. The officer or N.C.O. on duty moves about continually along the trenches inspiring confidence and gathering information. ‘Corporal, come here a minute, ’ one hears a voice say. ‘Yes, what is it?’ ‘Oh, I think I can see something moving in front,’ says the sentry, ‘just over there on the right.’ So the object is watched very closely for some minutes, still it does not move. ‘Try a shot,’ suggests the Corporal, but that does not move it, and so it is decided that the sentry has been looking at a post for so long that he eventually appears to see it move! These instances of optical illusion are very common and especially occur when every nerve has to be strained for the slightest sound or movement.

Although the sky is clear and the stars begin to twinkle, it is very dark, and so rockets are sent up, which open out into a very brilliant light, so that all the ground in front can be seen. Both sides have these, which are sent up now and then and are a very pretty sight. Away on the right a machine gun begins to send out its message of death, and then the rifles take up the strain until the whole line is marked by the quick flashes which pierce the darkness. After a time the firing dies down again, probably a German working party had been seen, shown up by the lights, and had promptly dispersed. Four loud bangs break the silence now, the Germans are getting rather annoyed and one of their batteries opens fire; the shells scream overhead and explode somewhere in the rear, doing no damage whatever. On a very dark night the glow of the shells coming over can be seen; they are forced through the barrel of a gun at such a tremendous rate that they seem red hot. From now right on through the night the sentries fire at any suspicious object, and the sharp crack of the German rifles can be heard in reply. Some of the bullets hit the protecting barbed wire and ricochet off, with a peculiar ring. Others come ‘ping, ping’ over the parapets, and some hit the raised emplacements with a dull thud. In certain parts of the line shots are noticed to come over at fairly regular intervals and always in the same spot, which means the enemy has fixed a rifle on that mark during the day, and is therefore able to fire accurately when darkness sets in. Far away, over the hill and the plains beyond, the thunder of heavy guns rolls continuously. High up in the sky the flashes can be seen, and one wonders how long it will be before the lovely country in front of us holding the German trenches and troops, will have the treatment that is being given to them where the guns are working.

When under shell fire, the chief feeling seems to be one of awe at its power, and the likelihood of going up in the air should one burst too close. At regular intervals the sentries are changed and so the long vigil goes on. Stretched out on the platforms some are sleeping, wrapped in their great coats and waterproof sheets, others are sitting up smoking and talking in lowered voices, and some are alone with their thoughts, thinking perhaps of home and those who made home what it is. Hark, what sound is that in front? Yes, it’s nearly one o’clock, just the time for the enemy to be about. ‘Wish it was lighter. I am sure there’s someone trying the wires,’ says the sentry. Yes, sure enough beyond the entanglements figures can just be discerned moving along, feeling the wire, one, two, three, why there’s seven of them. ‘All right, keep quiet, and we will bag them lower down’ orders the N.C.O., so he doubles round, and gets a few men ready for them. In a few minutes the Germans come creeping along, keeping low as to be hardly discernible. As they get opposite the waiting men, rapid fire is opened on them. Some stifled cries are heard and they quickly retire, one, however, replying to our fire. Evidently some were hit, but not seriously. Anyhow, no more have tried to pay us a visit. After this little frontier incident, everything soon gets quiet again. The men draw their coats and wraps in closer as it is now very cold, and this is the time when human vitality is at its lowest ebb. What a long night it seems. Will dawn never break?

The evenings are so very short now and the hours of darkness so many that a night seems unending. At last, however, the eastern sky is appearing lighter and gradually the stars disappear before the dawning light. Everybody breathes a sigh of relief, and those who have been on the watch are now free to turn in and forget for a time their arduous duties. The officer can now be seen coming round and giving those who desire it rum, to warm them up and keep colds and chills off. Needless to say, it is much appreciated and was surely never used to better purpose. Despite the fact that the troops have been standing in mud and water for hours and have had to work under the most trying conditions, colds are almost unknown. So thorough has been the training of the new Army that men who were rather on the delicate side of health and not very strong, are now fine fit men, hard as nails and ready for anything. The life has broadened their minds, widened their outlook, and enabled them to take most of the necessary hardships as a matter of course. England will get a finer and nobler nation for the threats she is undergoing, and realise more and more that her strength lies in her manhood. Therefore why not train every man to be fit to serve her, so that her power may be the instrument of good throughout the world? Of course, the reader will understand, much has of necessity been left out in this little article, but some idea may have been conveyed of what night-time is like out here. London has its Zeppelins to watch for, we have many, many other dangers to watch for, all from the same source.”

Sadly, by July that year, there was another newspaper article about Sidney:

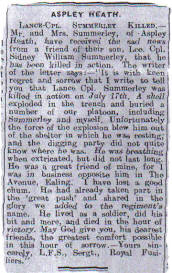

“ASPLEY HEATH – LANCE-CPL. SUMMERLEY KILLED

Mr. and Mrs. Summerley, of Aspley Heath, have received the sad news from a friend of their son, Lce. Cpl. Sidney William Summerley, that he has been killed in action. The writer of the letter says: – “It is with keen regret and sorrow that I write to tell you that Lance Cpl. Summerley was killed in action on July 17th. A shell exploded in the trench and buried a number of our platoon, including Summerley and myself. Unfortunately the force of the explosion blew him out of the shelter in which he was resting, and the digging party did not quite know where he was. He was breathing when extricated, but did not last long. He was a great friend of mine, for I was in business opposite him in The Avenue, Ealing. I have lost a good chum. He had already taken part in the ‘great push’ and shared in the glory we added to the regiment’s name. He lived as a soldier, did his bit and more, and died in the hour of victory. May God give you, his dearest friends, the greatest comfort possible in this hour of sorrow. Yours sincerely, L.F.S., Sergt., Royal Fusiliers.”

Sidney had a sister Mabel, who was working in Egypt during WWI as a nanny, where she met a wounded New Zealand soldier, convalescing from a wound received at Gallipoli. They returned home to England, and Mabel married James Leslie Hill in Woburn Sands in August 1917. James ended the war as 2nd Lieutenant with the Forces in Germany, and had been awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal. His daughter was born 6 days after the Armistice was signed. The family left England to live in New Zealand in 1919.

Sidney was killed in action on the Western front, aged 23. Listed on the Thiepval Memorial, Somme, France. Listed on the Woburn Sands Memorial. His army service papers have not survived.

Details kindly provided by Mr R. Davidson, of New Zealand, grandson of Mabel Summerley, from his family history. January 1916 letter discovered by John Taylor, Milton Keynes historian.

Page last updated Jan. 2019.